- Date:

Infocus - In contrast to the 1970s, central banks now have legal mandates for price stability and explicit targets for inflation – requiring them to act forcefully to ensure that any unavoidable temporary increase in inflation does not become permanent.

There is much concern about stagflation in market commentary at the moment. In this issue of Infocus, EFG Chief Economist Stefan Gerlach reviews the notion of stagflation and comments on the US experiences since 1970. In contrast to the 1970s, central banks now have legal mandates for price stability and explicit targets for inflation – requiring them to act forcefully to ensure that any unavoidable temporary increase in inflation does not become permanent.

Public concern about stagflation – an unfortunate combination of stagnating, or perhaps even negative, growth and high inflation – is rising because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Commentators are recalling the 1970s and early 1980s, a period associated in the US and many other countries with sharp declines in real GDP, inflation spikes above 10% per annum, the federal funds rate at almost 20% and volatile stock prices. This was not a happy episode for the US economy, and it is not surprising that the prospect of stagflation has caused concern.

In assessing the risk of stagflation, it is useful to take a step back and look at US economic data since the 1970s.

What is stagflation?

First, it is essential to understand what stagflation is. The simplest way to think about it is as a sharp contraction of the economy’s ability to produce goods and services at the current price level. In the 1970s and 80s, the causal factors were the massive increases in oil prices in 1974 and 1980. Overall, oil prices rose from US$3.90 per barrel in 1973 to US$37.40 per barrel in 1980 – that is, almost by a factor of ten.

The increase in the price of oil led to a surge in the cost of energy and in firms’ production costs. Higher oil prices eroded the purchasing power of wages and led to demand for compensatory wage increases. Since the oil price increase was relative to other prices, it could not be offset by economic policy. The result was an unavoidable decline in corporate profits – and therefore in stock prices – and in real wages.

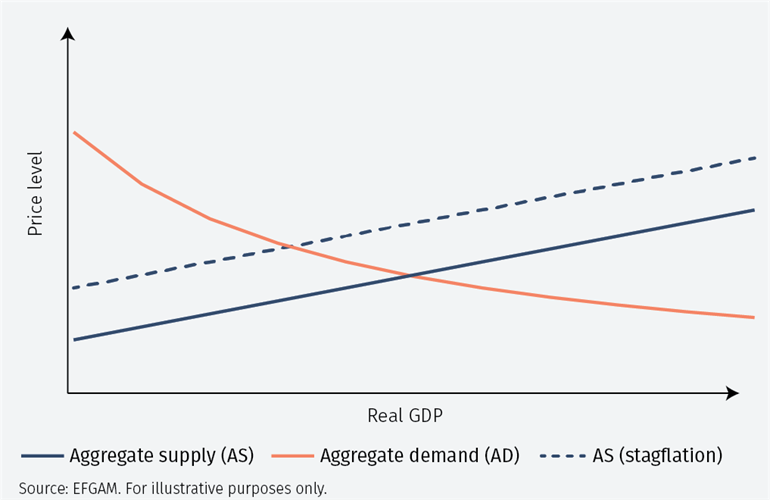

In terms of the familiar aggregate supply and demand analysis shown in Figure 1, one can think of a stagflation shock as entailing a shift of the economy’s aggregate supply schedule to the left (which indicates that at the going price level, firms would like to supply less output). For a given aggregate demand curve, the net effect will be downward pressure on real GDP growth and upward pressures on prices:

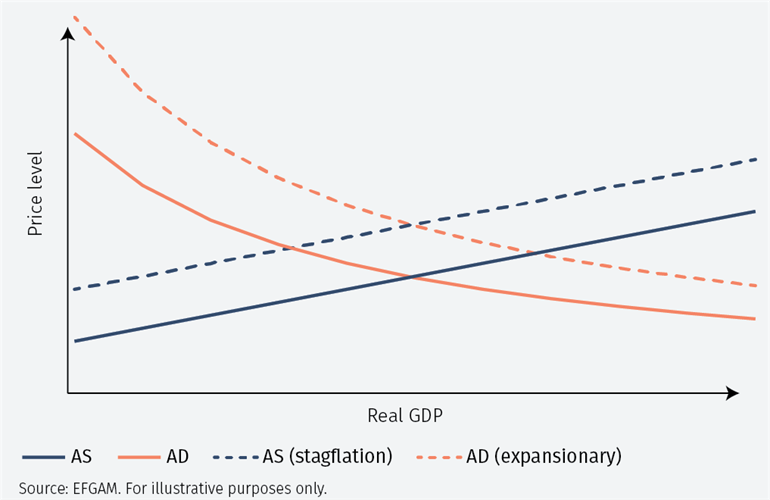

But the demand curve is likely to shift too. One possibility is that fiscal and monetary policymakers worry that the slowing of the economy will lead to a rise in unemployment. This was the case in the 1970s, when many policy makers responded by boosting aggregate demand. Such an expansionary policy will reduce or, depending on how strong it is, offset the decline in real GDP, at the cost of additional pressure on prices to rise, as shown in Figure 2.

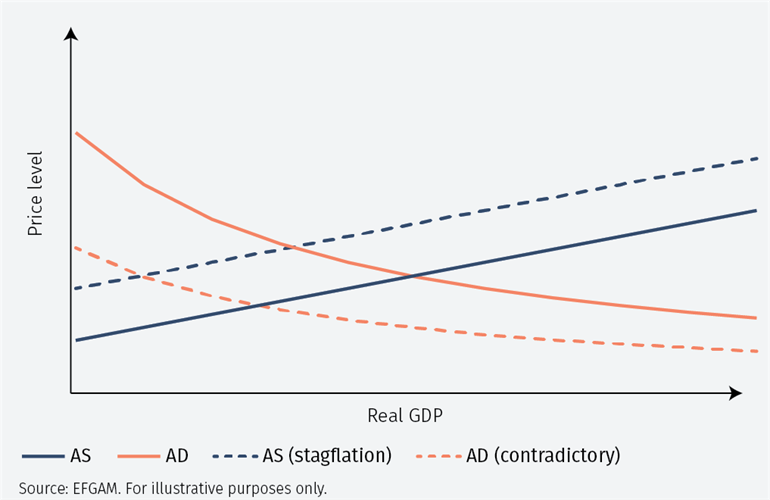

Alternatively, policy makers can adopt a contractionary policy response by reducing aggregate demand. That reduces the pressure on prices to rise but amplifies the decline in real GDP (Figure 3).

Of course, central banking has changed since the 1970s. One important difference is that inflation targets are now common. These limit the extent to which central banks can let inflation rise in response to a stagflationary contraction of aggregate supply.1

Recent US economic history

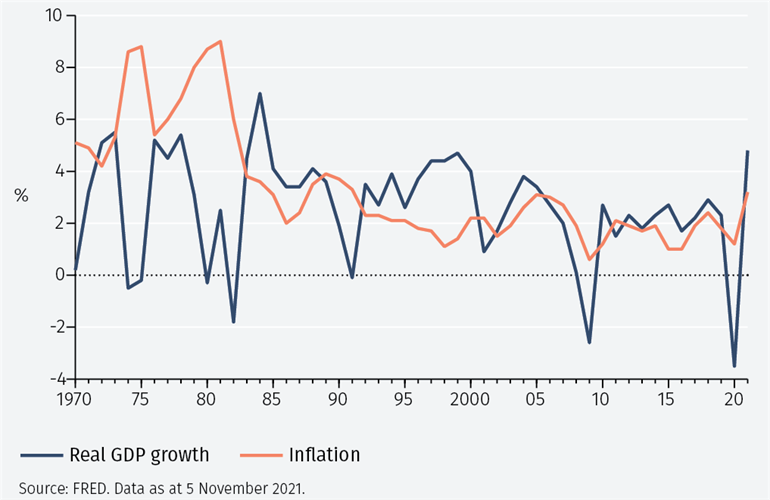

Using data on real GDP growth and inflation, it is possible to construct estimates of how aggregate supply and demand schedules have impacted the economy over time.2 Below we look at how aggregate supply and demand shocks have affected the economy, using annual data for the period 1970-2021.3

Figure 4 shows the growth rate of real GDP and inflation (as measured by the US GDP deflator) for the period 1970 to the first half of 2021. The oil price shocks between 1974 and 1980 lead to outright falls in real GDP and surges in inflation. It is this combination of stagnating growth and high inflation that is the defining characteristic of deflation.

The figure also shows deep recessions in 1982, caused by the Fed adopting tight monetary policy to reduce inflation from the very high levels of the late 1970s and early 1980s; and in 2009 as the Global Financial Crisis struck and again in 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic.

But, instead of looking at the fluctuations in real GDP growth and inflation, it is more interesting to look at the role played by shocks in aggregate supply and demand in causing these fluctuations.

To continue reading, please use the button below to download the full article.

1 Two factors provide central banks with some leeway in responding to contractionary supply shocks. First, the inflation targets are generally surrounded by a band that provide some margin of manoeuvre. For instance, if the target is 2%, ±1%, the central bank can let inflation rise to 3%. Second, price level shocks have generally a temporary effect on inflation. Central banks therefore sometimes disregard them in the expectation that the impact on inflation will have abated long before a monetary policy response would start to impact inflation.

2 To do so, some identifying assumption is needed to separate the shocks. Here the assumption is that the price elasticity of aggregate demand is minus one; this assumption implies that nominal GDP growth is determined by aggregate demand growth, while aggregate supply determines how demand is divided into real GDP growth and inflation.

3 The observation for 2021 is for the first half of the year. The estimates stem from a structural VAR(1) model for real GDP growth and inflation, using the identifying restrictions described in the previous footnote.

Important Information

The value of investments and the income derived from them can fall as well as rise, and past performance is no indicator of future performance. Investment products may be subject to investment risks involving, but not limited to, possible loss of all or part of the principal invested.

This document does not constitute and shall not be construed as a prospectus, advertisement, public offering or placement of, nor a recommendation to buy, sell, hold or solicit, any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. It is not intended to be a final representation of the terms and conditions of any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. This document is for general information only and is not intended as investment advice or any other specific recommendation as to any particular course of action or inaction. The information in this document does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of the recipient. You should seek your own professional advice suitable to your particular circumstances prior to making any investment or if you are in doubt as to the information in this document.

Although information in this document has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no member of the EFG group represents or warrants its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Any opinions in this document are subject to change without notice. This document may contain personal opinions which do not necessarily reflect the position of any member of the EFG group. To the fullest extent permissible by law, no member of the EFG group shall be responsible for the consequences of any errors or omissions herein, or reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein, and each member of the EFG group expressly disclaims any liability, including (without limitation) liability for incidental or consequential damages, arising from the same or resulting from any action or inaction on the part of the recipient in reliance on this document.

The availability of this document in any jurisdiction or country may be contrary to local law or regulation and persons who come into possession of this document should inform themselves of and observe any restrictions. This document may not be reproduced, disclosed or distributed (in whole or in part) to any other person without prior written permission from an authorised member of the EFG group.

This document has been produced by EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited for use by the EFG group and the worldwide subsidiaries and affiliates within the EFG group. EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority, registered no. 7389746. Registered address: EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited, Leconfield House, Curzon Street, London W1J 5JB, United Kingdom, telephone +44 (0)20 7491 9111.