- Date:

- Author:

- Joaquin Thul

The concept of smart cities was first used in the 1970s when the Community Analysis Bureau in Los Angeles, California, introduced the use of computer databases, cluster analysis and aerial photography to analyse population trends. This new technology was used to gather and interpret data related to demographics, housing and transport, giving policymakers additional information when proposing policy changes. Since then, this concept has been used by governments and investors to describe various initiatives to modernize cities, putting data and digital technology to work with the goal of improving the quality of life.

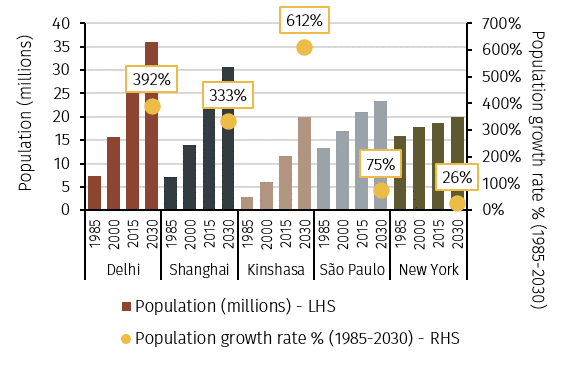

Cities today face two main dilemmas. The first one relates to demographics. In emerging markets, cities such as Delhi and Shanghai are expected to see an increase of their populations by 40% and 30% respectively by 2030. Similar growth rates in population are expected in Kinshasa, Sao Paulo, Mumbai and Cairo, see Figure 1. As cities become urbanized and over-populated the use of artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning and the Internet of Things (IoT) will become common across big cities, contributing to an improvement in traffic flows, energy efficiency, reduction in pollution and waste management, among other things.

The second dilemma is the new post-pandemic reality. In this new environment, people’s needs in both developed and emerging economies will change, shifting from work-centric to people-centric cities. Citizens will require access to a range of services, cultural and leisure facilities, as well as proximity to green spaces as part of their communities. Governments will need to invest in infrastructure to improve transport and access from suburban areas into city centres.

Source: HSBC, World Population Review and EFGAM

Therefore, it becomes important to understand what drives the new urbanization trends, what the new cities of the future will look like and where governments will need to invest to improve the cities’ appeal to their new users.

Urbanization

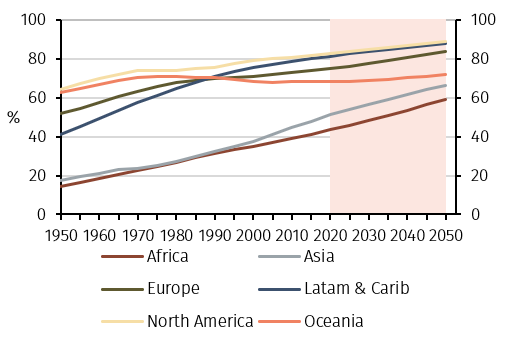

Through history, cities have grown as centres of trade, culture and economic development. The industrial revolution in Europe and the United States during the 18th century contributed to the rise in workers’ migration from rural areas into larger urban centres. The transition to an industrialization of manufacturing processes and the implementation of new technologies took almost 100 years, resulting in better economic conditions and a demographic change. According to the US Census Bureau, it was not until the late 1800s when the proportion of population living in rural areas dropped from 94% to 60% in the US. Nowadays approximately 80% of the population in US, UK and Germany live in urban areas. This proportion is lower in emerging economies such as China and India but is expected to increase in the coming years, see Figure 2.

Source: UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs and EFGAM.

The urbanization process has become a catalyst for the development of new technologies, improved housing constructions, better transport connectivity and overall drivers of economic growth. Interestingly, 80% of global GDP is currently contributed by urban environments, highlighting the importance of these big cities.1 Despite this, large urban centres are also part of the environmental problem. Although they represent less than 2% of the world’s surface, cities consume 78% of the world’s energy and produce more than 60% of greenhouse gas emissions.2 However, the drive to make cities more sustainable has gathered momentum, increasing pressure on policymakers and companies to invest in these improvements.

Cities of the future

The Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 accelerated some of the recent urbanization trends and the “new normal” will force governments to rethink urban planning and the use of public spaces. In developed economies, as people move to a model that allows them to work parts of the week from home, they will require different services. Faster internet connectivity and access to green spaces will become more relevant for young professionals that choose to settle in suburban areas. In emerging economies, only 50% of jobs are in the professional services sector. Therefore, the pandemic will have less of an effect in the urbanization of new areas.3 However, people there will require more efficient and cleaner transport to reduce commuting times, and the necessary infrastructure to tackle problems with security. Cities are expected to become more people-centric, as citizens get involved in community aspects. Issues related to their access to quality healthcare services will be key to attract people to urbanized areas. The creation of interconnected Smart Homes and solutions for remote education and work will enable people to spend more time at home. Additionally, cities will need to improve their connectivity. New infrastructure focused on mobility and transport congestion issues will be required. This will boost investment in faster wireless technology and the software needed to support these systems. Finally, sustainability will become a key characteristic of cities in the future. More often people will look for cleaner and cheaper energy sources for their homes, efficient construction, and better ways to access clean water and address issues with waste management.

Some of these projects can offer solutions to multiple problems. For example, investing in technology infrastructure has the potential to solve some of the issues with pollution, security, and traffic congestion. Governments are aware that data, and the infrastructure to analyse it, has become as important to their citizens’ welfare as power grids and transport systems.4

The multiplier effect of infrastructure

In addition to the benefits related to demographic and environmental changes, government investments in infrastructure have the potential of being more effective than other types of public spending in boosting economic growth over the medium term.

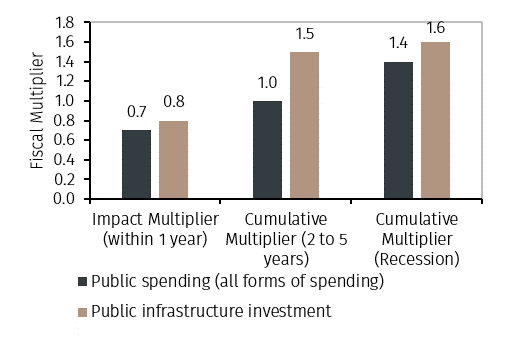

The G20 Action Plan in response to the Covid-19 pandemic revealed that investment in infrastructure initiatives such as roads, electricity grids, rail lines, telecommunications, water supply, airports and ports have an average multiplier effect of 0.8 over one year, which is marginally above the 0.7 effect from other forms of public spending. However, over the following two to five years infrastructure spending has a multiplier effect of 1.5, as opposed to 1.0 from other forms of spending, see Figure 3. Additionally, this multiplier effect is also larger during times of economic recession, adding to the counter-cyclical benefits of infrastructure investment.

Source: Global Infrastructure Hub.

A successful case: London Congestion Charge

The Congestion Charge Zone was introduced in London in 2003, based on Singapore’s Electronic Road Pricing system dating from the late ‘90s. Users register their vehicle online and pay a standard charge when driving within the Congestion Charge Zone in central London during peak traffic hours. This system is primarily enforced by automatic number-plate recognition, based on CCTV cameras which have been installed across the city. This removes the need to implement barriers and tollbooths to pay, which would cause delays and logistical problems.

Since the system was implemented the scheme has helped to reduce the traffic volume by 10% in central London. Additionally, it has contributed to the reduction in air and noise pollution and improved road safety in the city. Proceeds from this tax currently help subsidize London’s public transport system, making the majority of the city’s buses fully electric, and financing investments in cycle lanes across the city. In an attempt to reduce carbon emissions, the program was expanded in 2019 with the introduction of an Ultra-Low Emission Zone which applies a charge to vehicles that do not meet carbon emission standards.

The investment in technology for the implementation of this system has brought a series of benefits for the city. Problems with traffic congestion, environmental pollution, road safety, and the financing of green initiatives were addressed, at least partially, by this scheme.

Conclusion

The use of technology for urban planning has evolved over the years, shifting from a simple tool to analyse traffic data to a valuable resource to improve many aspects of urban life. Changes in demographics and the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic have accelerated the need for cities to implement some of these new technologies to make cities more liveable and sustainable. The implementation of some of these smart technologies has the potential of not only providing a cost-effective solution to many of the environmental and infrastructure needs faced by big cities, but also improve some of the quality-of-life indicators by 10%-30%.5 Smart cities are now expected to have efficient public transport systems, cleaner energy sources and greater public participation. Therefore, as cities become more interconnected and data-driven towards the changing needs of its citizens, investing in these new technologies will give the cities of the future an edge to attract individuals and companies.

Footnotes

1 World Bank, 2020

2 UN Habitat, 2021

3 Future Cities. The changing shape of urbanisation”, HSBC, 2021

4 The Economist, 2016.

5 “Smart Cities: Digital solutions for a more liveable future”. McKinsey Global Institute. June 2018.

Important Information

The value of investments and the income derived from them can fall as well as rise, and past performance is no indicator of future performance. Investment products may be subject to investment risks involving, but not limited to, possible loss of all or part of the principal invested.

This document does not constitute and shall not be construed as a prospectus, advertisement, public offering or placement of, nor a recommendation to buy, sell, hold or solicit, any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. It is not intended to be a final representation of the terms and conditions of any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. This document is for general information only and is not intended as investment advice or any other specific recommendation as to any particular course of action or inaction. The information in this document does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of the recipient. You should seek your own professional advice suitable to your particular circumstances prior to making any investment or if you are in doubt as to the information in this document.

Although information in this document has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no member of the EFG group represents or warrants its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Any opinions in this document are subject to change without notice. This document may contain personal opinions which do not necessarily reflect the position of any member of the EFG group. To the fullest extent permissible by law, no member of the EFG group shall be responsible for the consequences of any errors or omissions herein, or reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein, and each member of the EFG group expressly disclaims any liability, including (without limitation) liability for incidental or consequential damages, arising from the same or resulting from any action or inaction on the part of the recipient in reliance on this document.

The availability of this document in any jurisdiction or country may be contrary to local law or regulation and persons who come into possession of this document should inform themselves of and observe any restrictions. This document may not be reproduced, disclosed or distributed (in whole or in part) to any other person without prior written permission from an authorised member of the EFG group.

This document has been produced by EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited for use by the EFG group and the worldwide subsidiaries and affiliates within the EFG group. EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority, registered no. 7389746. Registered address: EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited, Leconfield House, Curzon Street, London W1J 5JB, United Kingdom, telephone +44 (0)20 7491 9111.