- Date:

- Author:

- Sam Jochim and Amanda Cotti

Infocus - Inflation has surged to levels not seen in decades due to rising commodity prices, supply chain bottlenecks and tight labour markets. These factors apply to most developed countries, but not to Switzerland where inflation remains low. In this edition of Infocus, GianLuigi Mandruzzato compares Swiss inflation to that in the US and the eurozone and draws some policy implications.

Strong domestic consumption and investment is driving GDP growth in India and the outlook appears positive, despite slowing global growth. In this edition of Infocus, Sam Jochim and Amanda Cotti look at India’s economy, its structural challenges and the opportunities that lie ahead.

Growth and inflation

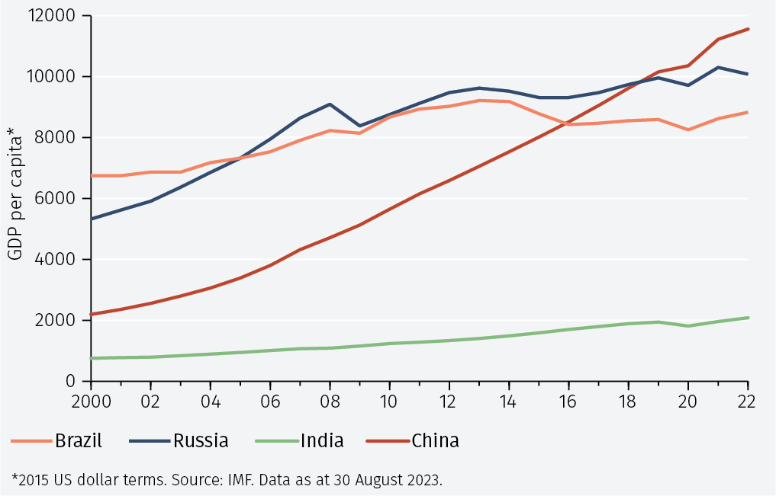

India’s economy is the sixth largest in the world based on GDP at constant prices in 2015 US dollars. The IMF projects it will grow around 6% per annum over the next five years, a faster pace than other BRIC nations (see Figure 1).

Following the pandemic-related contraction in fiscal year 20-21, India’s GDP rose 9.1% and 7.2% in fiscal years 21-22 and 22-23 respectively. Almost 60% of this growth was accounted for by private consumption, with over a third coming from capital expenditures, around 10% from government spending and trade detracting slightly from growth.

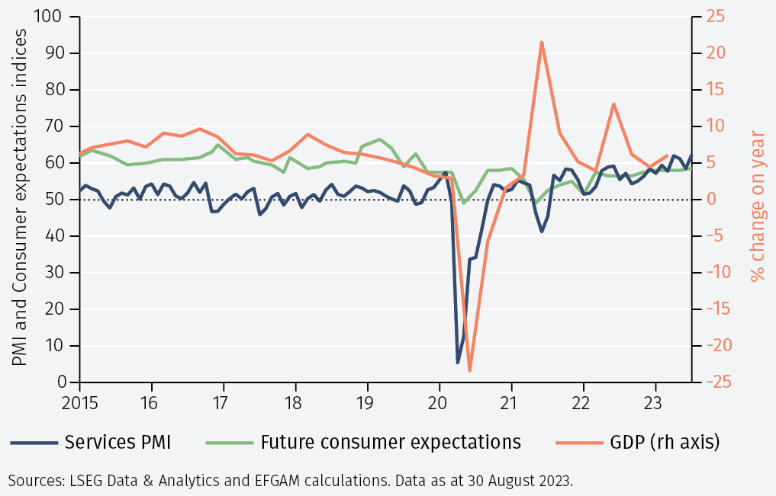

Given the strength of the services sector and the high level of consumer optimism in India, private consumption appears well placed to drive growth again in fiscal year 23-24 (see Figure 2).

Furthermore, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) believes banks and private companies have healthy balance sheets, while supply chain normalisation, business optimism and robust government capital expenditures are additional factors supportive of a renewal of the capex cycle.

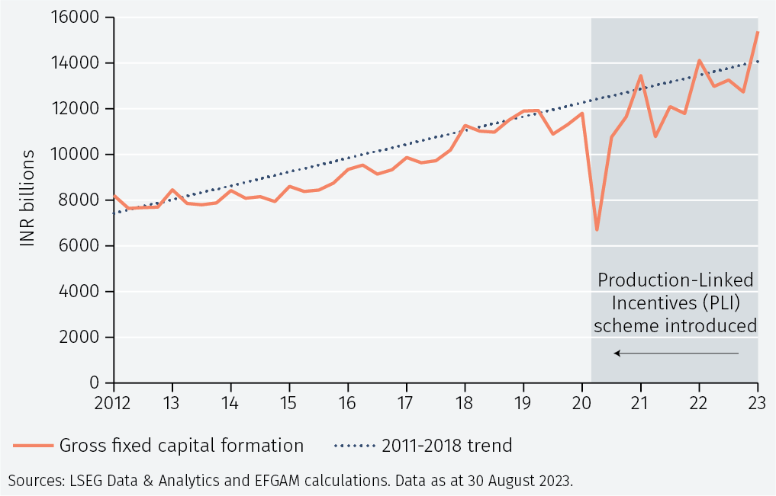

A further tailwind to growth comes from the government’s Production-Linked Incentives (PLI) scheme which was introduced in 2020. This scheme proposes financial incentives over five years to boost domestic manufacturing across 14 key sectors.6 Since the PLI’s introduction, fixed capital formation in India accelerated beyond its 2011-2018 trend implied level (see Figure 3). Further acceleration is possible in 2024 as protectionist policies, such as the impending import restriction on laptops and tablets, are implemented to encourage domestic production.

However, while protectionist policies can raise demand for domestic products in the short run, in the longer run they are more likely to reduce aggregate demand due to market inefficiencies which increase costs for consumers. The result could be a slower pace of GDP growth due to weaker aggregate demand.

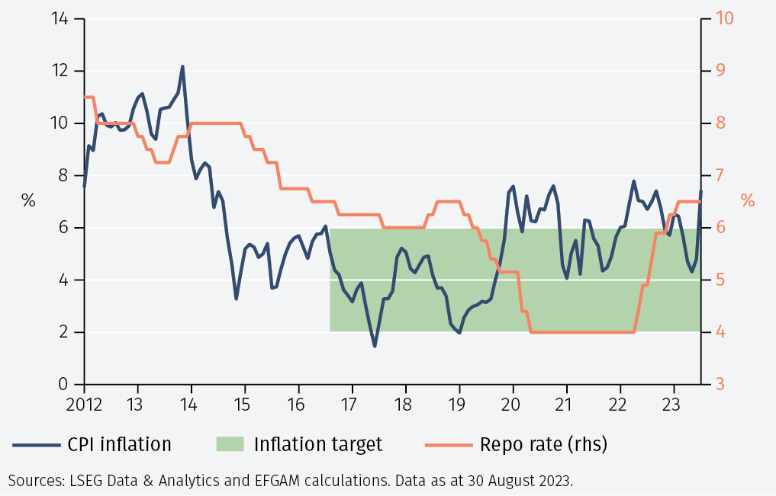

Turning to monetary policy, India adopted a flexible inflation targeting framework in 2016, formalising price stability as the primary policy objective. The RBI targets CPI inflation at 4% with a 2% tolerance band either side of the target.

Food accounts for around 46% of the CPI basket in India, making it an important determinant of inflation. Since food prices are more vulnerable to supply shocks than other goods and services, having a credible inflation target to anchor both inflation and inflation expectations is important.

Without such a target, long-run inflation expectations can drift due to supply shocks, on which monetary policy has little impact. If long-run inflation expectations are stable, supply shocks are less likely to lead to second-round effects and more likely to manifest themselves as one-off changes to the rate of inflation, i.e. they become transitory.

In May 2022, the RBI began raising interest rates with inflation above the upper end of its target range at 7.0% year-on-year. Having raised the repo rate by a cumulative 250 basis points to 6.5%, the central bank left rates unchanged at its last three meetings, while inflation fell to within its target range (see Figure 4).

Conditions were in place for interest rate cuts before the end of 2023. However, in July inflation increased once more above the RBI’s target range. This was driven by an increase in vegetable prices, reflecting the impact of a late start to the Monsoon season and uneven rainfall distribution, highlighting the vulnerability of inflation in India to agricultural supply shocks.

The RBI expects price increases to peak in the second quarter of the fiscal year at 6.2% before falling towards the midpoint of the inflation target over the next year. Monetary policy is therefore likely to remain restrictive for the remainder of 2023 to maintain the credibility of the inflation target. Interest rate cuts are possible in 2024 in the absence of further shocks.

Structural challenges, ambitions and reforms

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government announced an array of reforms upon his re-election for a second term in 2019. These focus on deregulation, attracting foreign investment and simplifying processes. Modi’s ambition is to achieve ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’, a phrase which means self-reliant India. Though most reforms have not been started and many of those that have remain incomplete, they hold the potential to enhance the business landscape for private companies and facilitate foreign investor access to India’s market. A nonexhaustive list of reforms is summarised in the Appendix.

A key aspect of achieving Atmanirbhar Bharat is Modi’s ‘Make in India’ plan. This plan was originally announced when Modi first took office in 2014. Many new policies have been announced during his second term aimed at boosting domestic production. The Production Linked Incentives scheme previously mentioned, for example, forms part of this.

While protectionist policies aimed at boosting domestic production may be popular among local producers, they often result in market inefficiencies which frustrate productivity gains. Furthermore, empirical studies have shown that the removal of trade barriers would significantly increase welfare in India.

This highlights a key problem with Atmanirbhar Bharat: it fails to address some of the structural problems facing India such as poor living standards and inefficient labour. Despite being the world’s sixth-largest economy, GDP per capita ranks one hundred and sixty-fifth. For context, India’s GDP per capita in 2022 was USD 2085, below the global median of USD 6205.

GDP per capita is a useful proxy for productivity. That India’s GDP per capita is the lowest of all the BRIC countries and almost ten times less than that of the US therefore represents both a challenge and a significant opportunity for growth (see Figure 5).

A key reform which could have a large impact in this area is the National Education Policy (NEP). The NEP came into effect in the 2023-24 academic year and focuses on access, equity, quality and accountability. Although this should help improve living standards and increase productivity, it will take time for India to reap the rewards. For those entering the new system in 2023, most will not enter the working population as high-skilled workers for at least another fifteen years.

2024 election & foreign policy

Despite a lack of progress with many important reforms, Modi benefits from an approval rating of almost 80%. A general election will be held in India between April and May 2024 and he is likely to retain the premiership for another five years. However, Modi’s victory is not a certainty. His ruling party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), lacks popularity.

If Modi retains power, India will likely maintain its current approach to foreign policy, which has been based on a closer alignment with Western countries and away from its strained relationship with China. A 58-point joint communique with the US was released following a meeting with Biden in June, reaffirming the commitment of the two countries to the US-India Comprehensive Global and Strategic Partnership. The West appears determined to reduce its dependence on China, presenting India with a valuable opportunity to establish itself as a geopolitical powerhouse.

However, India’s approach will likely be measured. Despite differing geopolitical stances, India and China are closely aligned when it comes to trade. China ranks top among India’s import origins and third as an export destination, with over USD 100 billion of goods and services flowing between the two economies in 2021.

Conclusion

In summary, the outlook for India is positive. GDP growth is projected to be around 6% per annum for the next five years and despite the current surge, inflation is expected to return to its target range, opening the door for rate cuts in 2024.

However, average living standards in India are disappointingly low. Moreover, additional structural problems such as inefficient labour persist. Modi’s reforms, intended to achieve ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’, have not yet addressed these structural issues and may yet aggravate them. Nevertheless, groundwork is now being laid for India’s future, with the National Education Policy having the potential to mitigate some of these problems.

This will take time and the challenge is not insignificant. Re-election for Modi in 2024 could see a fresh set of reforms introduced. In any case, India appears to be on the right path and has the potential for a prosperous future.

Important Information

The value of investments and the income derived from them can fall as well as rise, and past performance is no indicator of future performance. Investment products may be subject to investment risks involving, but not limited to, possible loss of all or part of the principal invested.

This document does not constitute and shall not be construed as a prospectus, advertisement, public offering or placement of, nor a recommendation to buy, sell, hold or solicit, any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. It is not intended to be a final representation of the terms and conditions of any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. This document is for general information only and is not intended as investment advice or any other specific recommendation as to any particular course of action or inaction. The information in this document does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of the recipient. You should seek your own professional advice suitable to your particular circumstances prior to making any investment or if you are in doubt as to the information in this document.

Although information in this document has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no member of the EFG group represents or warrants its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Any opinions in this document are subject to change without notice. This document may contain personal opinions which do not necessarily reflect the position of any member of the EFG group. To the fullest extent permissible by law, no member of the EFG group shall be responsible for the consequences of any errors or omissions herein, or reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein, and each member of the EFG group expressly disclaims any liability, including (without limitation) liability for incidental or consequential damages, arising from the same or resulting from any action or inaction on the part of the recipient in reliance on this document.

The availability of this document in any jurisdiction or country may be contrary to local law or regulation and persons who come into possession of this document should inform themselves of and observe any restrictions. This document may not be reproduced, disclosed or distributed (in whole or in part) to any other person without prior written permission from an authorised member of the EFG group.

This document has been produced by EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited for use by the EFG group and the worldwide subsidiaries and affiliates within the EFG group. EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority, registered no. 7389746. Registered address: EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited, Park House, 116 Park Street, London W1K 6AP, United Kingdom, telephone +44 (0)20 7491 9111.