- Date:

Infocus - Is Swiss fiscal virtue too much of a good thing?

The eurozone economy is recovering from the pandemic and inflation is now consistent with the ECB’s objective. Nevertheless, the outlook remains highly uncertain. In this edition of Infocus, Stefan Gerlach and GianLuigi Mandruzzato look at the prospects for monetary and fiscal policies.

The news from the eurozone economy is encouraging, as evidenced by PMI surveys and the EU Commission’s Economic Sentiment Index reaching their highest levels in several years. The EU Commission raised its GDP growth forecasts to 4.3% for 2021 and 4.4% for 2022 from the 3.8% in both years expected in January. The level of GDP is thus projected to return to pre-pandemic levels next year.

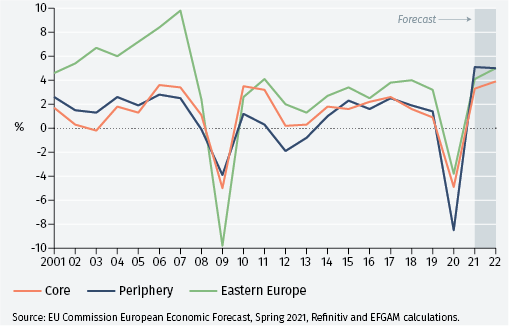

Despite the improved outlook, due to the acceleration of vaccinations and the easing of Covid restrictions, differences in economic performance among eurozone member countries are evident (see Figure 1). Furthermore, economies in the “core” and Eastern Europe are likely to close the activity gap caused by the pandemic faster than those in the “periphery”.1

This disparity highlights the importance of the Next Generation EU plan, including the Recovery and Resilience Plan, in reducing growth differentials within the eurozone. Italy is a case in point: over the past fifteen years, Italy’s relatively slow growth trimmed 0.3 percentage points off eurozone average annual growth, or one-fifth of its estimated growth potential.

Looking forward, the eurozone will benefit indirectly from the Biden administration’s fiscal stimulus in the USA and from solid growth in China. Demand from the eurozone’s export markets will grow in excess of 7% on average in 2021-22, driving exports and fixed investments.

The outlook for private consumption hinges on how households will dispose of the savings accumulated since the start of the pandemic. The fact that the increased savings have been concentrated among the wealthiest, who have a lower propensity to consume, will limit the rebound in household demand. Furthermore, the ongoing pandemic could lead to continued precautionary saving. Nevertheless, consumption spending is likely to rebound strongly in the near term from low levels and as the situation normalises further.

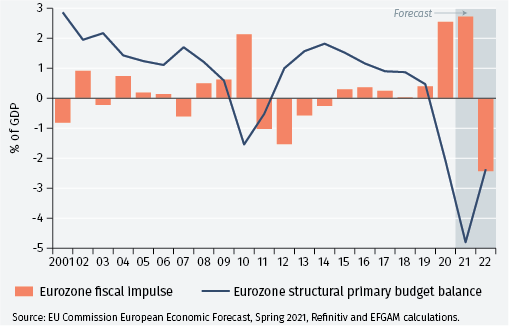

Turning to fiscal policy, the EU Commission estimates that the fiscal impulse will be close to 3% of GDP in 2021, a slight increase from last year (see Figure 2).2 Based on current legislation, fiscal policy is expected to be less expansionary in 2022, i.e. the public deficit will be smaller. However, the EU Commission has recently announced that the Stability and Growth Pact will remain suspended in 2022 as downside risks to growth remain, including that of a pandemic resurgence. As Economic and Financial Affairs Commissioner Gentiloni said, it is important not to repeat past mistakes of being “too quick in restricting the policy support”. It seems likely that the drag on next year’s growth from fiscal policy will be significantly lower than currently estimated. At the same time, it is important to ensure sustainability of public finances, especially in economies where public debt is high. Once again, how Italy balances these two needs will be important for the eurozone.

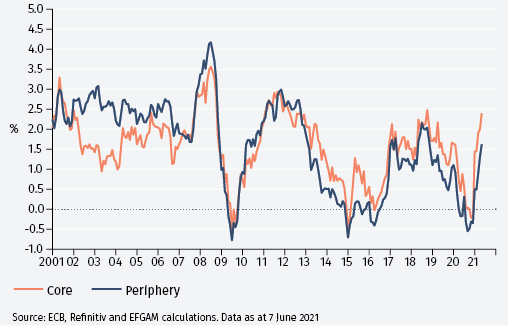

In the eurozone as in the US, inflation pressures have been rising recently, both in the core and periphery (Figure 3). With eurozone-wide inflation reaching 2.0% in May, it is natural that calls are made for the ECB to consider when and how to reduce policy accommodation.

However, two considerations urge caution.

First, the jump in annual headline inflation from -0.3% in December 2020 to 0.9% in January 2021 was disproportionally impacted by the surge of headline inflation in Germany, the largest eurozone economy, from -0.7% to 1.6%. This jump was amplified by the normalisation of VAT rates, measures in the government’s climate package, and an update of the HICP weights that were more extensive than usual.3 These factors are all one-off and are unlikely to be repeated.

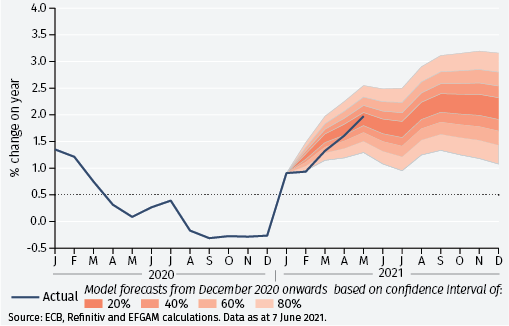

Second, forecasts suggest that HICP annual inflation is evolving much as expected after January. To see this, Figure 4 contains an illustrative forecast for the period February – December 2021 of eurozone headline inflation, using data ending in December 2020.4 Interestingly, actual inflation of 2% in May is very close to the 1.9% central forecast.

The forecasts call for annual inflation to rise gradually over the year, reaching 2.1% in December. The average for the year is 1.8%, marginally stronger than the ECB’s March projection of 1.5%.5 To the extent that this forecast is similar to the ECB’s forecasts, fears that inflation is about to take off seem exaggerated.

With economic activity rebounding and inflation reaching 2%, members of the Governing Council in favour of less accommodative policy will push for an early end to the PEPP.6

They are unlikely to be successful.

First, the ECB has made clear it will look through the current temporary rise in inflation as it aims at maintaining a high degree of accommodation until it is confident that inflation, including core inflation, is “robustly” converging towards the objective of “below, but close to, 2%”. In March, ECB staff macroeconomic projections had inflation at 1.5% for Q3 2023, a level that is not close enough to 2% to warrant a tightening of monetary policy.

Furthermore, a major shift in ECB policy seems unlikely before the outcome of the ECB’s strategy review has been announced. Most obviously, if that leads to the adoption of compensation mechanisms for the low inflation of recent years (i.e. allowing above-target inflation for some time), any plans for a substantial tapering of bond purchases are likely to be delayed.

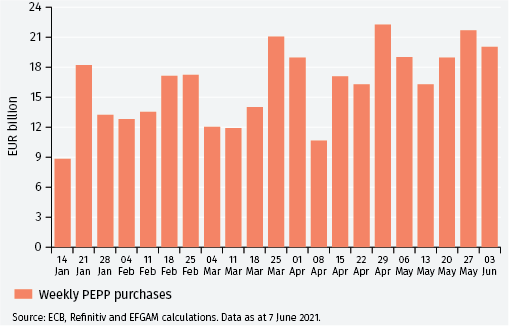

In the meantime, the Governing Council will seek to ensure the “favourable financing conditions” necessary to promote recovery. The role of the PEPP therefore remains central and the barometer of the ECB’s monetary policy stance is the pace of weekly bond purchases. After the announcement at the end of March of a “significant increase” in PEPP purchases to counteract the rise in German government bond yields and the widening of spreads of other eurozone government bonds, weekly average purchases increased by more than 30% to almost EUR 18.5bn from around EUR 14bn in the first months of the year (see Figure 5 overleaf).

The measure was only partially successful, at least judging by the moderate increase of eurozone government spreads and German bond yields relative to the US. However, it seems likely that the Governing Council will reiterate its commitment to keep PEPP purchases high in the coming months to consolidate the economic recovery.

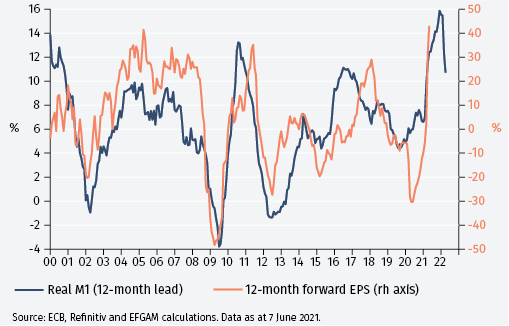

A mix of economic strengthening, moderate inflationary pressures and expansive fiscal and monetary policies will support the corporate sector and financial markets. Corporate profits are rising and expectations point to further improvements in the coming months, consistent with the increase in liquidity conditions (see Figure 6). If the earnings of listed companies (in the MSCI EMU index) follow the profile of the real M1 money supply, as has broadly occurred since the birth of the euro, their growth over the next twelve months will be close to, if not higher than 20% from current levels.

Conclusions

The eurozone growth outlook has improved, inflation has risen and fiscal policy is expected to remain supportive. Many commentators hence wonder if the ECB will soon announce a tapering of its bond purchases. However, this seems premature due to remaining downside risks to growth and the ECB’s own projections that inflation will fall short of the “below, but close to, 2%” objective until the end of 2023.

Rather, the Governing Council’s focus on maintaining favourable financing conditions points to a high pace of bond purchases continuing during the summer. Continued accommodation from fiscal and monetary policy will support eurozone financial assets.

Footnotes

1 Core countries are Austria, Belgium, Finland, Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. Peripheral countries are Cyprus, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Malta, Portuga,l and Spain. Eastern European countries are Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia and Slovenia.

2 The fiscal impulse is defined as the change in the structural primary balance.

3 See Monthly Report, Deutsche Bundesbank, February 2021, p. 51.

4 A second-order AR model, incorporating a MA(12) term, is estimated on monthly data for years 2000-2020.

5 The ECB’s projections can be found here: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/projections/html/ecb.projections202103_ecbstaff~3f6efd7e8f.en.html.

6 The PEPP (Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme) is the asset purchase scheme launched by the ECB in March 2020. The initial EUR 750bn amount was increased by EUR 600bn on 4 June 2020 and by EUR 500bn on 10 December, for a total of EUR 1,850bn.

Important Information

The value of investments and the income derived from them can fall as well as rise, and past performance is no indicator of future performance. Investment products may be subject to investment risks involving, but not limited to, possible loss of all or part of the principal invested.

This document does not constitute and shall not be construed as a prospectus, advertisement, public offering or placement of, nor a recommendation to buy, sell, hold or solicit, any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. It is not intended to be a final representation of the terms and conditions of any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. This document is for general information only and is not intended as investment advice or any other specific recommendation as to any particular course of action or inaction. The information in this document does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of the recipient. You should seek your own professional advice suitable to your particular circumstances prior to making any investment or if you are in doubt as to the information in this document.

Although information in this document has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no member of the EFG group represents or warrants its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Any opinions in this document are subject to change without notice. This document may contain personal opinions which do not necessarily reflect the position of any member of the EFG group. To the fullest extent permissible by law, no member of the EFG group shall be responsible for the consequences of any errors or omissions herein, or reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein, and each member of the EFG group expressly disclaims any liability, including (without limitation) liability for incidental or consequential damages, arising from the same or resulting from any action or inaction on the part of the recipient in reliance on this document.

The availability of this document in any jurisdiction or country may be contrary to local law or regulation and persons who come into possession of this document should inform themselves of and observe any restrictions. This document may not be reproduced, disclosed or distributed (in whole or in part) to any other person without prior written permission from an authorised member of the EFG group.

This document has been produced by EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited for use by the EFG group and the worldwide subsidiaries and affiliates within the EFG group. EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority, registered no. 7389746. Registered address: EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited, Leconfield House, Curzon Street, London W1J 5JB, United Kingdom, telephone +44 (0)20 7491 9111.