- Date:

The recent burst of inflation in the US and in many other countries has led investors to wonder whether the entire inflation environment has changed.

Question: If I hired a fund manager with perfect foresight as to which stocks would be the best performers over the next five years, what kind of drawdown would I have to bear in order to get the absolute best possible returns?

We decided to simulate the performance of such a “perfect foresight” fund manager to determine the drawdowns relative to the benchmark one may incur if such a strategy was selected.

Our “perfect foresight” fund manager looked at up to 1,000 of the largest companies listed in the United States in June 1972 (the earliest month for which we have easily available data) and then looked forwards to see which stocks would produce the best return over the next five years. The manager then constructed an equally weighted portfolio of the 50 companies that would produce the top returns over the next five years.

Each quarter our “perfect foresight” manager would look forward and select companies that would again produce the best performance over the following five years and then rebalance the portfolio back to include these stocks.

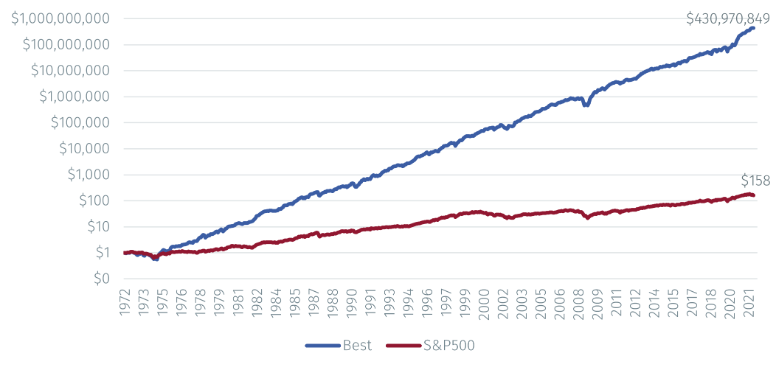

Needless to say, the performance from such a fund manager would be astonishing. $1 invested in such a portfolio in June 1972 would be worth $430,970,849 at the end of April 2022, for a whopping 48.83% return per annum. This compares to investing in the S&P 500 which would have turned $1 into $158, for a return of 10.67% per annum.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to the future. Source: FactSet and EFGAM calculations.

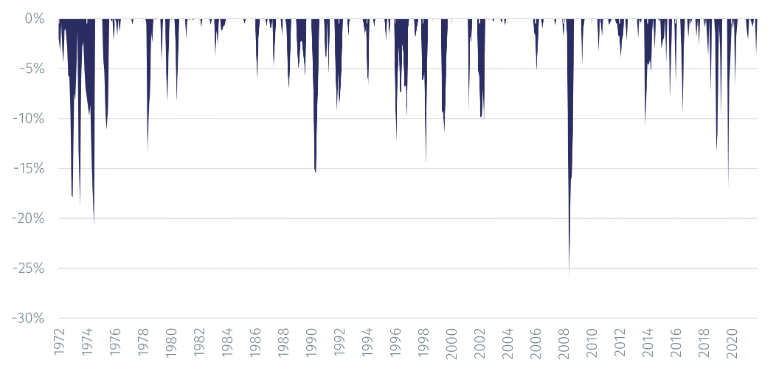

So how much volatility would one have to bear to turn $1 into $430,970,849? We analysed the monthly drawdown of such a portfolio against the S&P 500 assuming our manager maintained the discipline of holding onto those 50 best performing companies despite the volatility. In order the generate this 48.83% return per annum an investor in the fund would need to stomach:

- 92 months where the fund was below the S&P500 by 5% or more;

- 24 months where the fund was below by 10% or more;

- 11 months where the fund was below by 15% or more;

- 2 months where the fund was below by 20% or more;

- 1 month where the fund was below by 25% or more.

The maximum drawdown relative to the S&P 500 an investor would suffer would be 26.1% which occurred during the 2008 financial crisis. Other recent notable periods would also produce gut wrenching drawdowns. During the Dotcom bust of 2000 the fund would draw down by 11.4%, and during the Covid-19 crisis of 2020, by 16.8%.

Source: FactSet and EFGAM calculations.

Hiring a fund manager with perfect foresight is of course not possible, but what about hiring one that consistently picks a significant number of stocks that outperform the benchmark?

Using a Monte Carlo simulation, we constructed three stylised managers. One constructs a portfolio where just 50% of the stocks outperform over the next 5 years with quarterly rebalancing, another with 60% of the stocks outperforming, and a third with 70% of the stocks outperforming. How do the returns and drawdowns of these managers compare to the “perfect foresight” manager? Over the 50-year period, the manager with a 50% “hit ratio” delivered a 8.06% return, but with a maximum relative drawdown of 76% - not very attractive compared to the S&P500 at a 10.67% per annum. The manager with a 60% hit ratio delivered a 11.38% return, a healthy 71bps of alpha per annum, but you would need to stomach a 49% maximum relative drawdown. The exceptionally good manager with a 70% hit ratio delivered a 14.47% annual return, or 407bps of alpha per annum, but even with this an investor would need to remain steadfast with a maximum relative drawdown of 34% compared to the benchmark.

In practice fund managers are often fired for much smaller drawdowns than the ones above, and even the “perfect foresight” fund manager would most likely have been fired many times during their tenure as manager of this fund.

Even a fund managed with perfect foresight would experience many periods of significant relative drawdowns in delivering the best possible portfolio return. The key lesson from this is that if one is invested in an investment process which delivers proven long term returns, one has to be willing to experience significant drawdowns to obtain better than benchmark performance. The key criteria for assessing whether or not to retain a fund manager should not be short periods of underperformance but rather the quality of their underlying investment process and how consistently their process is applied.