- Date:

- Author:

- Sam Joochim

Infocus - Inflation has surged to levels not seen in decades due to rising commodity prices, supply chain bottlenecks and tight labour markets. These factors apply to most developed countries, but not to Switzerland where inflation remains low. In this edition of Infocus, GianLuigi Mandruzzato compares Swiss inflation to that in the US and the eurozone and draws some policy implications.

Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has a significant lead in the opinion polls for India’s general election. A third term in power is likely to be confirmed on 4 June and so it is important to assess the economic implications of another five years of a Modi premiership. In this edition of InFocus, Economist Sam Jochim delves further into these topics.

Executive summary

One of Modi’s key ambitions for his third five-year term as Prime Minister is to grow the manufacturing sector as a share of gross value added (GVA). His ‘Make in India’ initiative forms a key part of the strategy to achieve this, aiming to attract foreign direct investment into 14 key sectors. However, the policy’s success has been debatable. While it is likely that there is a fresh push in Modi’s prospective third term, headwinds remain and there are clear areas for policy improvement such as reducing import tariffs.

Infrastructure development will form another key area of focus for Modi. In his first ten years as Prime Minister, he focussed on building roads and electrifying railways. These infrastructure targets were ambitious and often they were not achieved, but in attempting to reach them, there was often a significant acceleration in progress. In his third term it is likely that the focus shifts to producing more electric vehicles and developing infrastructure which will help India in its efforts to achieve netzero by 2070.

Despite his popularity among Indian voters, Modi faces challenges in his prospective third term. Unemployment is the most prominent concern among Indian voters. Youth unemployment is high by historical standards and female labour force participation is low. Reforms to India’s outdated labour laws could help tackle these issues.

Election appears a formality

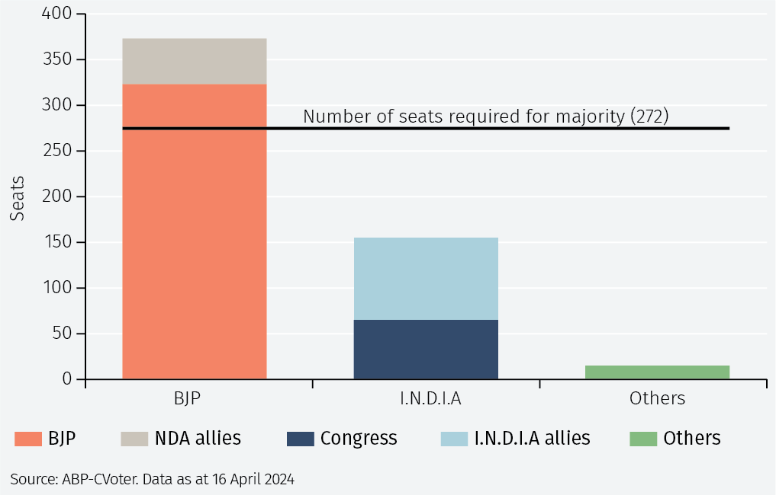

Voting in India’s general election began on 19 April and is split into seven phases, lasting 44 days and ending on 1 June. The election is expected to be the largest in the world, with 968 million people eligible to vote, and there is little doubt about the outcome. The National Democratic Alliance (NDA), led by Modi’s BJP, is projected to win 373 seats – well above the 272 needed to secure a majority in the Lok Sabha (lower house of Parliament). The opposition coalition, the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (I.N.D.I.A), led by Mallikarjun Kharge’s Congress Party, is expected to win just 155 seats (see Figure 1).

Although a majority in the Lok Sabha is seemingly a formality for the BJP-led NDA, passing legislation in India requires approval at both levels of Parliament. The NDA are four seats short of a majority in the Rajya Sabha (upper house of Parliament) and this could act as a constraint on the speed with which legislation is passed, though it is unlikely to prevent Modi from pushing through his agenda.

Modi’s key ambitions: manufacturing and trade

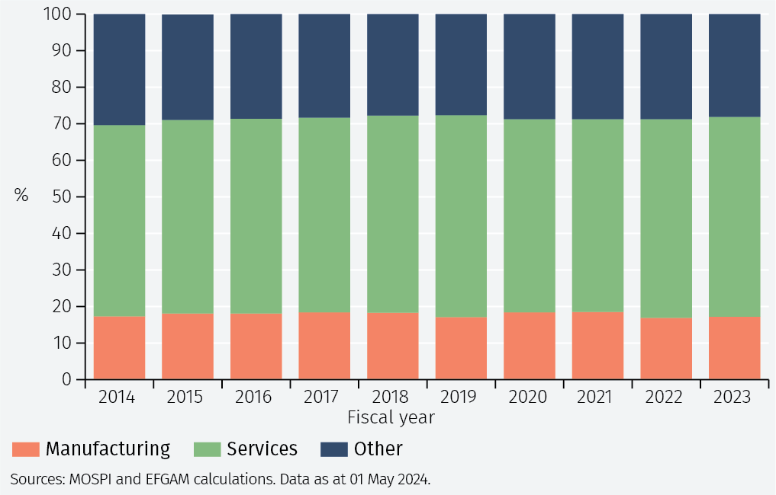

One of Modi’s key ambitions for his third five-year term as Prime Minister is to grow the manufacturing sector as a share of GVA. Since Modi took office in 2014, the manufacturing sector has accounted for just under 20% of GVA (see Figure 2). This is despite the BJP’s ‘Make in India’ initiative which aims to “transform India into a global design and manufacturing hub”.

One of the key pillars of this initiative is the Production-Linked Incentives (PLI) scheme, which was introduced in 2020. The scheme proposes financial incentives with the goal of boosting domestic manufacturing across 14 key sectors. Its introduction was aligned with the release of an updated foreign direct investment (FDI) policy that aims to improve the ease with which foreign companies can invest in India.

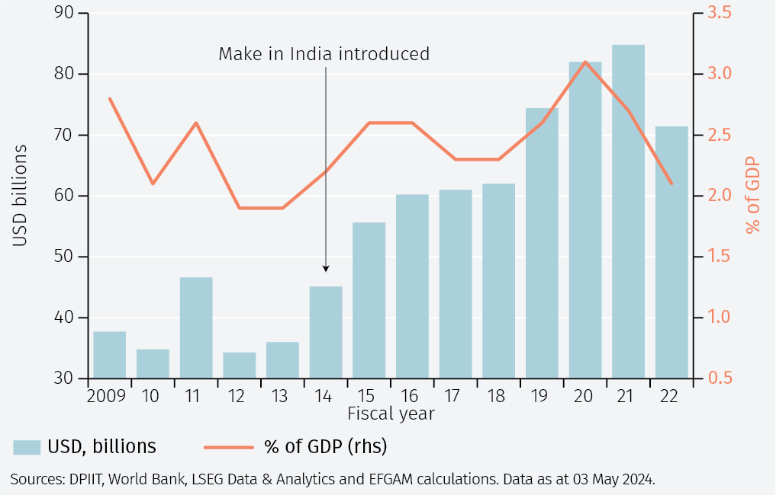

However, the success of these policies is debatable. Although FDI has risen in USD terms since the ‘Make in India’ initiative was introduced in 2014, it has not risen as a percentage of GDP (see Figure 3). Furthermore, most of the flows have not been into sectors that PLIs focus on. In fact, the PLI sectors accounted for 31% of FDI from fiscal year (FY) 2000 to FY 2013 but their share of FDI dropped to 26% when measured from FY 2000 to FY 2022. The sectors the Indian government wants to grow may not necessarily be viewed as good investments by foreign investors.

Click here to continue reading

Important Information

The value of investments and the income derived from them can fall as well as rise, and past performance is no indicator of future performance. Investment products may be subject to investment risks involving, but not limited to, possible loss of all or part of the principal invested.

This document does not constitute and shall not be construed as a prospectus, advertisement, public offering or placement of, nor a recommendation to buy, sell, hold or solicit, any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. It is not intended to be a final representation of the terms and conditions of any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. This document is for general information only and is not intended as investment advice or any other specific recommendation as to any particular course of action or inaction. The information in this document does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of the recipient. You should seek your own professional advice suitable to your particular circumstances prior to making any investment or if you are in doubt as to the information in this document.

Although information in this document has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no member of the EFG group represents or warrants its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Any opinions in this document are subject to change without notice. This document may contain personal opinions which do not necessarily reflect the position of any member of the EFG group. To the fullest extent permissible by law, no member of the EFG group shall be responsible for the consequences of any errors or omissions herein, or reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein, and each member of the EFG group expressly disclaims any liability, including (without limitation) liability for incidental or consequential damages, arising from the same or resulting from any action or inaction on the part of the recipient in reliance on this document.

The availability of this document in any jurisdiction or country may be contrary to local law or regulation and persons who come into possession of this document should inform themselves of and observe any restrictions. This document may not be reproduced, disclosed or distributed (in whole or in part) to any other person without prior written permission from an authorised member of the EFG group.

This document has been produced by EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited for use by the EFG group and the worldwide subsidiaries and affiliates within the EFG group. EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority, registered no. 7389746. Registered address: EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited, Park House, 116 Park Street, London W1K 6AP, United Kingdom, telephone +44 (0)20 7491 9111.