- Date:

Infocus - Latin America's slow and uneven economic recovery

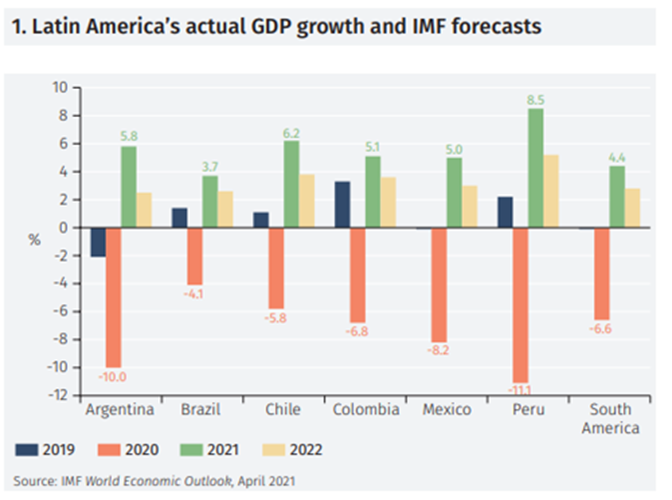

Latin American and Caribbean countries were negatively impacted last year by the combination of the global recession, falling commodity prices, declining global trade and the pandemic, resulting in a decline in the region’s 2020 GDP of over 8%. In this issue of Infocus, Joaquin Thul discusses the 2021 outlook for Latin American economies.

According to the IMF, Latin America will grow by approximately 4.6% in 2021, which would beat the region’s 30-year average growth rate of 2.6%. The IMF expects the region to benefit this year from stronger global growth, improving international trade, rising commodity prices and a gradual recovery in services activity, thanks to wider availability of Covid-19 vaccines. Additionally, the region is expected to be supported by the spillover impact from higher GDP growth in the US in 2021, following the approval of a USD 1.9 trillion fiscal stimulus plan. Estimates from the OECD show the marginal benefit to the economies of Mexico and Brazil resulting from the US stimulus will be about 0.8% and 0.6% of GDP respectively in the first year after the plan’s approval.1

However, the pick-up in economic activity is expected to be slow and uneven across the region for several reasons. First, the lack of control of the virus across Latin America has resulted in a recent resurgence of Covid-19 cases and deaths. Countries will be under pressure to maintain restrictions on activity and mobility, delaying economic recovery. Second, although stimulus plans will need to be maintained through the year, there are doubts over how these programmes will be financed to balance longer-term fiscal sustainability. Third, the region’s busy political calendar in 2021 is also likely to prompt further government spending in countries with limited fiscal space.

Resurgence of Covid-19 cases and inflationary pressures

A year after the Covid-19 outbreak, Latin American countries have used a range of available tools to support their economies while failing to control the spread of the virus. As of April 6th, the region registered an average of 3,500 daily deaths attributed to Coronavirus, over 35% of the world’s daily deaths, and over 110,000 daily new cases of the virus, approximately 20% of the world’s total. Vaccination programs have had a slow start across the region, apart from Chile where more than a quarter of the population has already received at least one dose. The slow progress of vaccinations, means that on average only ten out of every 100 people in South America have received a vaccine so far.2

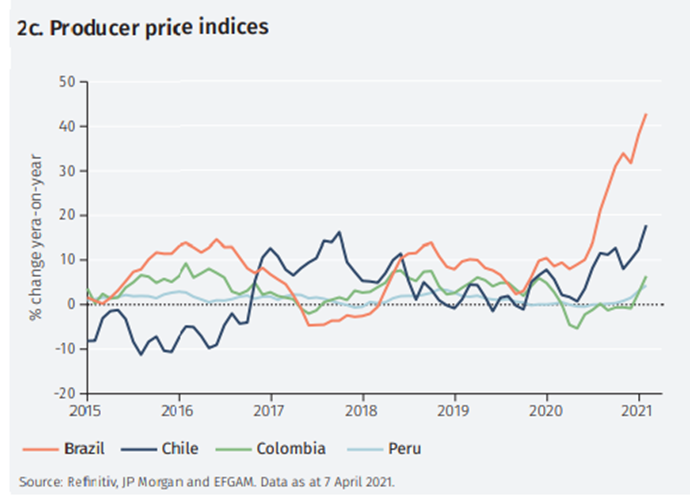

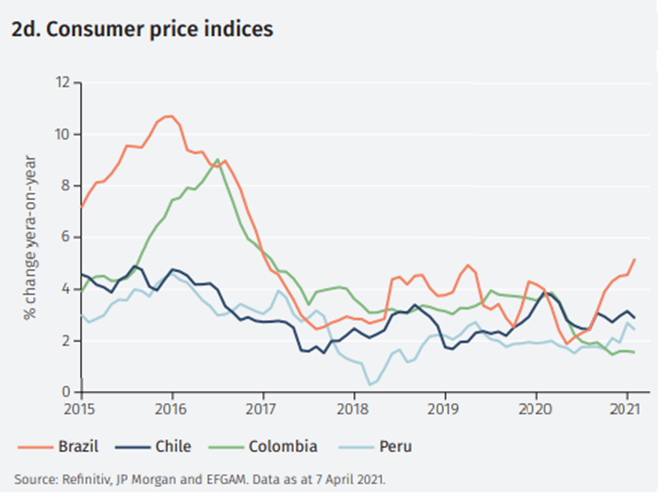

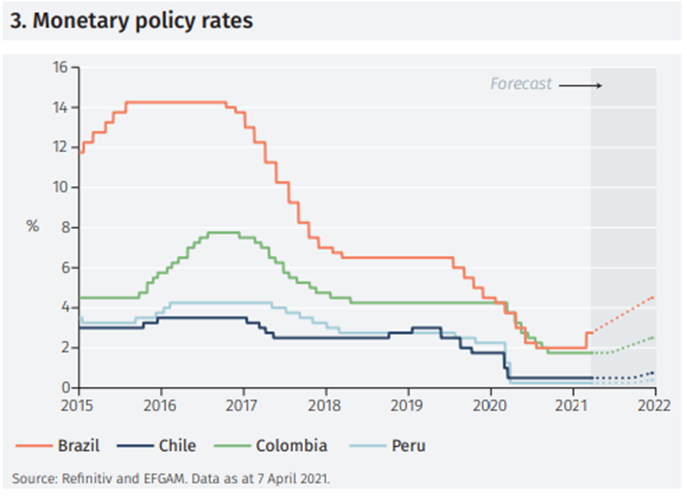

If the number of new Covid-19 cases remains high and vaccine rollouts are delayed, governments will need to extend their stimulus programs at a time when concerns about fiscal sustainability and inflation are rising. The combination of the strong monetary support measures implemented in 2020 and the recent increase in food and energy prices have fuelled inflationary pressures. Last year, central banks in Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Peru and Mexico cut interest rates to historic lows. Additionally, Chile, Colombia and Brazil turned to quantitative easing in 2020 for the first time.

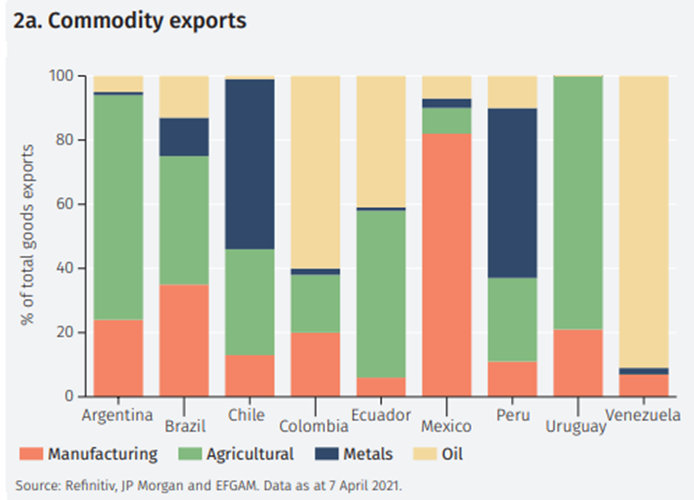

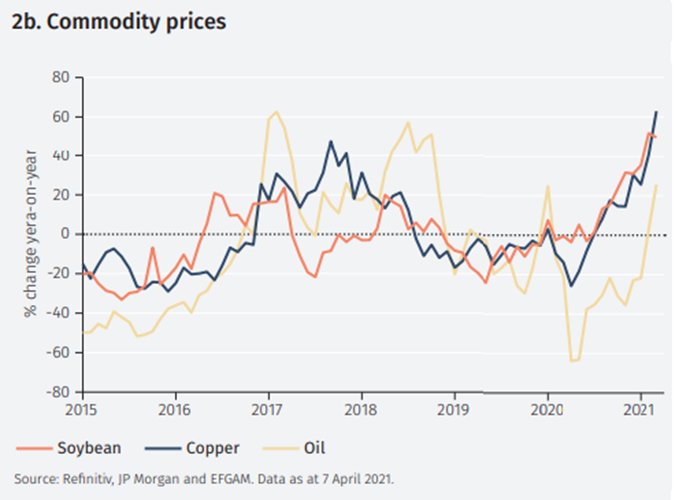

The increase in global demand for manufactured products and commodities in 2021 will contribute to the pick-up in economic activity in Latin America. However, the impact on growth will vary by country depending on each country’s exports and imports, see Figures 2a and 2b.

Chile and Peru, both exporters of industrial metals, will benefit from the 60% increase in copper prices over the last year. Although soybean prices have increased by 50% year-on-year, favouring exporters such as Argentina, dry weather conditions have reduced production by almost 10%. Additionally, Argentina increased tariffs on soybean exports to 33% in January, aimed at controlling food prices. Brazil will also benefit from the recovery in agricultural prices, but the country’s need to import light crude oil, as opposed to refining the heavier domestic oil, has created upward pressure on domestic energy prices, as evidenced by the 3. Monetary policy rates producer price index, see Figure 2c. Similar pressures have been observed in Chile, Colombia and Peru. These indicators normally provide a lead on future consumer prices and will weigh on central banks’ decisions on monetary policy, see Figure 2d.

2. Rise in commodity prices will fuel gradual tightening of monetary policy in 2021

On 17 March, Brazil was the first country to tighten monetary policy with a 75bps increase in the Selic rate, the first increase in six years. While inflation pressures have gradually increased due to commodity price rises, negative output gaps i.e. the actual output below potential output, will help to keep inflation contained in most of the region, allowing central banks in Peru and Chile to delay any interest rate hikes until the end of 2021, see Figure 3.

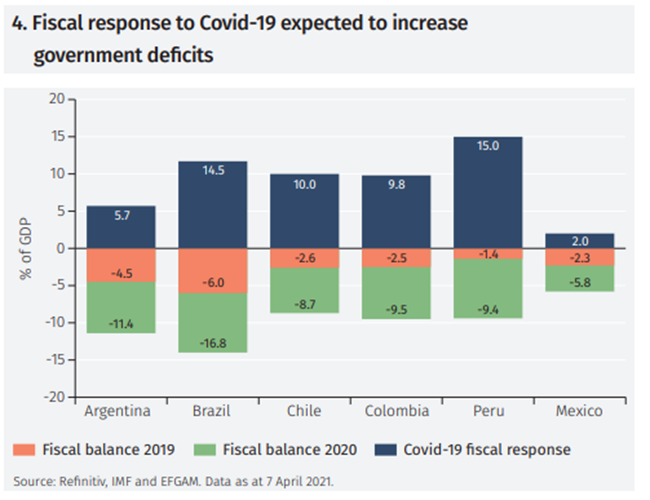

Limited scope for further fiscal stimulus

To support the economic recovery in 2021, countries will also need to maintain some of the fiscal plans from 2020. Last year fiscal stimulus was mixed across the region, with countries having to balance the need for fiscal discipline against providing necessary support during the pandemic, see Figure 4.

Peru and Brazil deployed large fiscal stimuli worth 15% and 14.5% of GDP respectively. Prior to the pandemic, Peru had a fiscal deficit of 1.4% of GDP and a debt-to-GDP ratio below 30%. However, despite implementing the largest fiscal package in the region the economy suffered a contraction of 14% in 2020 and the unemployment rate doubled to 14.5%.

Brazil was in a difficult position at the start of the pandemic, with a deficit of 6% of GDP and gross debt of 80% of GDP. Congress approved an increase in fiscal spending, temporarily overruling the spending cap, financed by an increase in debt which pushed the debt ratio close to 100% of GDP and the government’s fiscal deficit to 17% of GDP. Brazil’s GDP declined by 4.1% in 2020, less than elsewhere on the continent, but it came at the cost of weak fiscal accounts and fears that more stimulus will be needed if the country fails to control the spread of the virus.

Mexico and Argentina followed different strategies. Argentina’s economy was already under stress before the pandemic, with debt of 90% of GDP and annual inflation above 50%. The fiscal stimulus in Argentina, equivalent to 5.7% of GDP, was constrained by limitations on the country’s ability to issue new debt following the recent USD 65 billion debt restructuring.

In Mexico, authorities prioritized fiscal stability and delivered a prudent stimulus package worth 2% of GDP. Household consumption was supported last year by direct government transfers and a pick-up in remittances which increased by USD 40 billion, representing 3.8% of GDP. Despite this, Mexico’s GDP fell by 8.5% in 2020 and the fiscal deficit is expected to surpass 5% of GDP in 2021.

Politics take centre stage

Election years historically have not been periods during which Latin American governments undertake large spending cuts or tax hikes. This year, Presidential elections in Ecuador and Peru in April will be influenced by the outcome of the Covid-19 crisis. In June, Mexico will elect all new members of the Lower House of Congress. Argentina’s mid-term elections in October will test President Fernandez’s power within a divided Peronist party and his handling of the health crisis. In Chile, a Constitutional Convention will be elected in April and general elections are scheduled for November (see Figure 5). In Brazil, although Presidential elections are not scheduled until the fourth quarter of 2022, President Bolsonaro has lost political support in favor of former President Lula. Therefore, although governments might acknowledge the need to consolidate the large fiscal deficits incurred during the crisis, this is unlikely to happen in 2021.

Conclusion

The pick-up in commodity prices and the recovery in global demand will be a tailwind for 2021 GDP growth in the region. Countries with greater trade links with the US will benefit from the spillover of its recently approved stimulus package. However, the pick-up in GDP growth in 2021 is expected to offset only part of the decline generated by the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020.

The health crisis is far from being controlled in the region: the number of cases and deaths continue to increase and vaccination campaigns started slowly, limiting the economic rebound this year. Equity markets have already reflected some of the risks ahead. While Mexico and Chile performed strongly in Q4 2020 and could receive a boost from a recovery in US activity and a pick-up in commodity prices respectively, Argentina and Brazil have been weak driven by domestic policy issues, see Figure 5.

Growth in Latin America will remain slow and uneven during the first half of this year as the region gradually returns to normal levels of activity. With less space for stimulus policies than developed economies, countries will have to focus on controlling the virus and vaccinating their populations first, aiming for a faster recovery in the second half of 2021.

Footnotes

1 OECD Interim Economic Outlook Presentation. March 2021

2 OurWorldInData.org. Data as at 7 April 2021.

Important Information

The value of investments and the income derived from them can fall as well as rise, and past performance is no indicator of future performance. Investment products may be subject to investment risks involving, but not limited to, possible loss of all or part of the principal invested.

This document does not constitute and shall not be construed as a prospectus, advertisement, public offering or placement of, nor a recommendation to buy, sell, hold or solicit, any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. It is not intended to be a final representation of the terms and conditions of any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. This document is for general information only and is not intended as investment advice or any other specific recommendation as to any particular course of action or inaction. The information in this document does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of the recipient. You should seek your own professional advice suitable to your particular circumstances prior to making any investment or if you are in doubt as to the information in this document.

Although information in this document has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no member of the EFG group represents or warrants its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Any opinions in this document are subject to change without notice. This document may contain personal opinions which do not necessarily reflect the position of any member of the EFG group. To the fullest extent permissible by law, no member of the EFG group shall be responsible for the consequences of any errors or omissions herein, or reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein, and each member of the EFG group expressly disclaims any liability, including (without limitation) liability for incidental or consequential damages, arising from the same or resulting from any action or inaction on the part of the recipient in reliance on this document.

The availability of this document in any jurisdiction or country may be contrary to local law or regulation and persons who come into possession of this document should inform themselves of and observe any restrictions. This document may not be reproduced, disclosed or distributed (in whole or in part) to any other person without prior written permission from an authorised member of the EFG group.

This document has been produced by EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited for use by the EFG group and the worldwide subsidiaries and affiliates within the EFG group. EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority, registered no. 7389746. Registered address: EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited, Leconfield House, Curzon Street, London W1J 5JB, United Kingdom, telephone +44 (0)20 7491 9111.