- Date:

Infocus - the surge of central bank digital currencies

In recent years a growing number of digital platforms have allowed companies to accept payments in Bitcoin. In addition, social media company Facebook has launched its own digital currency, Libra. Such digital currencies have been in the spotlight over the past few months due to the strong performance of Bitcoin which recently hit a new all-time high. Partly as a result of their popularity central banks have become increasingly interested in digital currencies. In this issue of Infocus, Joaquin Thul looks at the characteristics of digital currencies and how Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) could become a complement to cash in the future.

Today over 45% of daily global retail transactions are facilitated via digital methods such as contactless card payments and mobile phone transfers. The development of third-party mobile payment apps such as Apple Pay, Android Pay and Alipay, which are expected to reach over one billion users in 2020, and increased mobile phone penetration have contributed to the growth in the use of digital payments.1

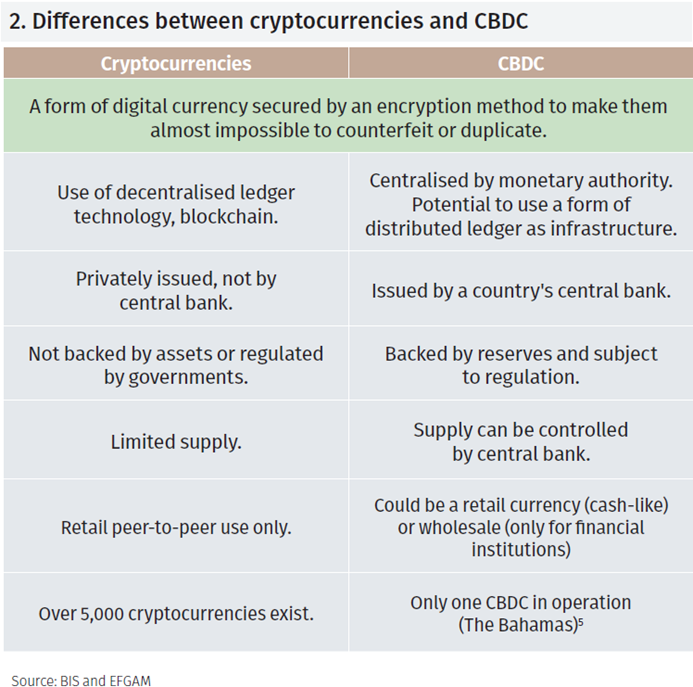

As at end 2019 less than 1% of global digital payments took place via digital currencies.2 The term ‘digital currency’ refers to a specific form of money which is only available in electronic form, is stored in applications such as electronic wallets, and which is accessible only through electronic devices. Digital currencies are secured by an encryption method that prevents them from being counterfeited or duplicated. The details are stored using a distributed ledger technology (DLT) that contains large chronological datasets of transaction history. Bitcoin, Ethereum and Litecoin are examples of these currencies, also called as cryptocurrencies, which use a decentralised form of DLT called blockchain.

Although the use of cryptocurrencies to pay for day-to-day transactions has not yet become commonplace, over the last year payment platform company BitPay has enabled companies such as AT&T to accept payments in Bitcoin.3 Social media companies have also started to get involved, with Facebook launching its own digital currency, Libra.

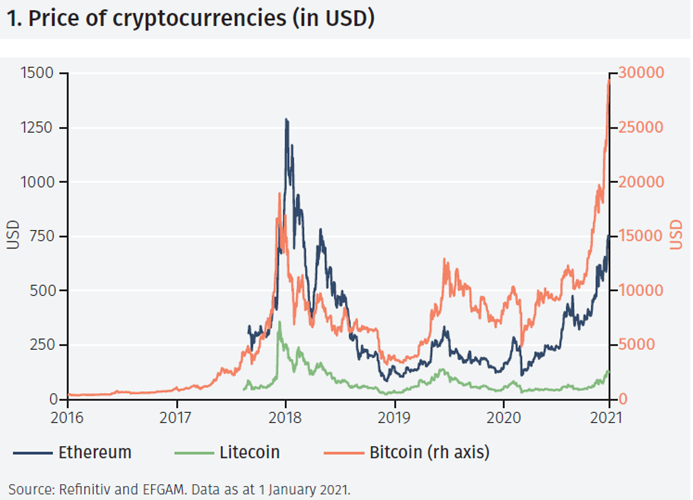

The increase in popularity of privately-issued digital currencies has been reflected in the recent rise in the price of Bitcoin, which has increased by over 300% since March 2020, hitting a new all-time high over USD 30,000 (see Figure 1).

Another characteristic of privately-issued cryptocurrencies is the limited supply available. In the case of Bitcoin, approximately 18.5 million Bitcoins have been issued, or mined, out of a maximum possible of 21 million. Therefore, the limited residual supply could have contributed to the recent sharp price increase.

Regardless of the reason for the surge in Bitcoin’s price, the popularity of cryptocurrencies has increased significantly over the last few years, reflected by the increase in the global market capitalisation of cryptocurrencies from USD 237 billion in 2019 to USD 537 billion in 2020.4 However, restrictions on their use for everyday payments, the lack of regulation and concerns over their use to facilitate illegal activities have so-far hindered their development as a mainstream form of digital payment. Furthermore, the high volatility and limited liquidity of Bitcoin and other digital currencies makes them inappropriate as a store of value – accepting payment in Bitcoin for an everyday item such as a cup of coffee may result in a significant shift in value in a short space of time when converted back to a traditional currency such as US dollars or euros.

Separately, in response to the change in consumer payment trends, central banks have become interested in the technology behind cryptocurrencies, which could help them develop a potential complement to existing forms of digital payments. However, it is important to differentiate between central bank digital currencies (CBDC) and cryptocurrencies issued by private firms, summarised in Figure 2.

A report by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) highlights that central banks have become concerned about the declining use of cash, which in some countries was accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic. However, there are ongoing debates regarding the need to introduce a digital currency issued by central banks and the potential benefits and challenges this could bring to the financial system.6

Research on the issuance of digital currencies as a means of payment has focused on three main areas. In economies where a large proportion of transactions have become digital, central banks want to ensure customers continue to have access to a publicly regulated, peer-to-peer, means of payment, backed by reserves and with the same characteristics as cash as a unit of account and store of value. In addition, CBDCs could increase financial inclusion in areas with low banking infrastructure or high levels of informality. Also, the issuance of a wholesale CBDC, accessible only to financial institutions as a new instrument to settle transactions between them and with the central bank, could help improve the speed of payment settlements.7

However, there remain a series of challenges in the implementation of CBDCs. Although the potential issuance of a digital currency could complement central banks’ monetary policy tools by providing an additional way to inject or withdraw funds into or out of the economy, it could also undermine the financial stability of commercial banks. In an indirect model, commercial banks distribute the CBDC to end users while they maintain reserves deposited with the central bank. In the direct model, central banks distribute CBDCs to end users, becoming a direct competitor to commercial banks and potentially risking their financial stability. The ease of access to a liquid asset that can be safely stored and is backed by the central bank could accelerate bank runs in times of uncertainty if customers turn away from commercial bank deposits.

In addition, while most CBDCs would be issued for domestic use, if one CBDC were to be adopted across multiple countries it could dilute a country’s monetary sovereignty by reducing the attractiveness of the local currency. In the case of inflationary economies, this could potentially accelerate the process of dollarisation.

Finally, the increase in the demand for privacy, as seen by the rollout of GDPR directives across the EU in 2018 and the intensification in regulation against money laundering and financing of illegal activities, means that any central bank regulated currency will have to strike a balance between observing the appropriate rules and regulations and the privacy of its users.

In summary, the issuance of digital currencies by central banks still has considerable hurdles to overcome and it is not entirely clear that central banks will want to embark in issuing a form of cryptocurrency which could disrupt the functioning of their financial systems. However, in some specific cases, retail CBDCs could complement the use of cash or help with financial inclusion.

A key difference with existing digital payment methods, such as Apple Pay, which are used for transactions between businesses and consumers, is that CBDCs could also operate for peer-to-peer payments. However, it is not expected that cash will cease to exist as the safest form of money. In designing CBDCs, consideration will need to be given both to the safety and stability of central bank money and the convenience and accessibility of electronic payments.

Footnotes

1 WorldPay Global Payments Report, 2020.

2 WorldPay Global Payments Report, 2020.

3 https://about.att.com/story/2019/att_bitpay.html

4 CoinMarketCap

5 On 20 October 2020, the Sand dollar became the first CBDC, representing the digital version of the Bahamian dollar (BSD). The central bank wanted to leverage from the 90% mobile device penetration in the population to solve a problem of low access to banking infrastructure across the country’s archipelago of more than 700 islands and cays. Issuing a digital currency, which can operate 24-hours a day as a peer-to-peer digital payment, became a way to improve financial inclusion. The CBDC has a 1:1 peg to the BSD, which is in turn pegged 1:1 to the US dollar.

6 The ECB Governing Council announced the purchase of Government bonds in January 2015, but President Draghi hinted at it in August 2014 at the Federal Reserve’s annual Economic Policy Symposium in Jackson Hole.

Important Information

The value of investments and the income derived from them can fall as well as rise, and past performance is no indicator of future performance. Investment products may be subject to investment risks involving, but not limited to, possible loss of all or part of the principal invested.

This document does not constitute and shall not be construed as a prospectus, advertisement, public offering or placement of, nor a recommendation to buy, sell, hold or solicit, any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. It is not intended to be a final representation of the terms and conditions of any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. This document is for general information only and is not intended as investment advice or any other specific recommendation as to any particular course of action or inaction. The information in this document does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of the recipient. You should seek your own professional advice suitable to your particular circumstances prior to making any investment or if you are in doubt as to the information in this document.

Although information in this document has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no member of the EFG group represents or warrants its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Any opinions in this document are subject to change without notice. This document may contain personal opinions which do not necessarily reflect the position of any member of the EFG group. To the fullest extent permissible by law, no member of the EFG group shall be responsible for the consequences of any errors or omissions herein, or reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein, and each member of the EFG group expressly disclaims any liability, including (without limitation) liability for incidental or consequential damages, arising from the same or resulting from any action or inaction on the part of the recipient in reliance on this document.

The availability of this document in any jurisdiction or country may be contrary to local law or regulation and persons who come into possession of this document should inform themselves of and observe any restrictions. This document may not be reproduced, disclosed or distributed (in whole or in part) to any other person without prior written permission from an authorised member of the EFG group.

This document has been produced by EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited for use by the EFG group and the worldwide subsidiaries and affiliates within the EFG group. EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority, registered no. 7389746. Registered address: EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited, Leconfield House, Curzon Street, London W1J 5JB, United Kingdom, telephone +44 (0)20 7491 9111.