- Date:

Infocus - Although inflation is reaching levels not seen for many years, central banks in most advanced economies hesitate to raise interest rates.

Although inflation is reaching levels not seen for many years, central banks in most advanced economies hesitate to raise interest rates. In this issue of Infocus, EFG Chief Economist Stefan Gerlach explains why that may be so.

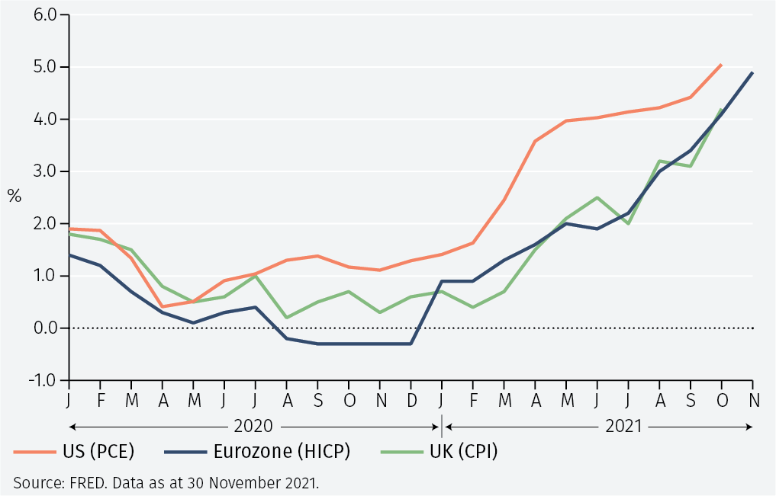

Inflation has risen sharply in recent months. In November, HICP inflation in the eurozone reached 4.9% (according to Eurostat’s flash estimate), PCE inflation in the US reached 5.0% year-over-year in October while UK CPI inflation was 4.2% (Figure 1). Nevertheless, the Federal Reserve (Fed), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of England have left interest rates unchanged. Furthermore, the Fed and the ECB signalled that they will not raise interest rates for many more months.

While several central banks in Latin America and Eastern Europe – including Brazil, Chile, Columbia, Mexico, Peru, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Romania – have raised rates, central banks in the most advanced economics seem loath to do so.

Reaction functions

Looking at central bank ‘reaction functions’ makes it even more difficult to understand why central banks are not raising interest rates. Reaction functions capture the idea that central banks set interest rates in relation to a few observed variables, in a numerically stable way. For instance, the celebrated ‘Taylor rule’ holds that the Fed’s setting of the Federal funds rate between 1987-1993 could be seen as determined by a simple equation or ‘rule’.

According to the rule, the Federal funds rate is well captured by the neutral real interest rate plus the rate of inflation, plus ½ times the deviation of inflation from 2%, plus ½ times the size of the output gap.1 Using data from FRED, the Fed’s public data base,2 the Taylor rule suggests that the Federal funds rate should now be 8.55%. Plainly, if the Fed were to set interest rates at this level, the US economy would collapse. A more relevant implication of the Taylor rule is that the Federal funds rate should rise by 150 basis points in response to a one percentage point increase in inflation.

But no central bank sets interest rates according to a fixed rule with the help of a pocket calculator. There are four main reasons for that. In declining order of importance for explaining why central banks do not raise interest rates now, they are:3

- First, central banks do not react to inflation and economic activity but to the underlying disturbances that cause economic fluctuations. A rise in inflation that is due to a rise in aggregate demand for goods and services is more likely to trigger an interest rate increase than an increase in inflation due to a contractionary supply-side shock. While increases in demand boost the economy and make it able to withstand higher interest rates, a contraction of supply reduces economic activity, implying that higher interest rates risk triggering a recession.

- Second, the expected persistence of economic shocks matters. Since monetary policy impacts inflation with lags of between 6 and 12 quarters, it makes little sense to respond to a surge in inflation if the rise is likely to be temporary.

- Third, reaction functions disregard many other factors that are important when setting interest rates. These include the state of the financial system, which determines how effective monetary policy is, and inflation expectations that may move very little in response to movements in observed inflation.

- Fourth, the neutral real interest rate (r*) is not constant, but appears to have fallen to close to, or even just below, zero. As r* declines, a central bank must reduce the interest rate it sets.4

All these factors are difficult to assess, particularly in real time. Doing so calls for plenty of good judgement. This is why central banks almost always set interest rates using a committee (such as the Fed’s Federal Open Market Committee, the ECB’s Governing Council or the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee), which discusses how and why the state of the economy has evolved since the last policy meeting.

Overall, reaction functions are too simple to be used to set monetary policy in practice.

Reaction functions

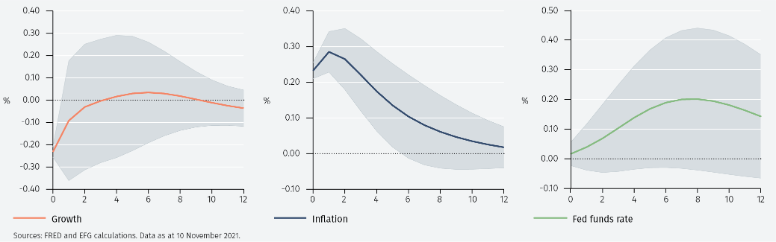

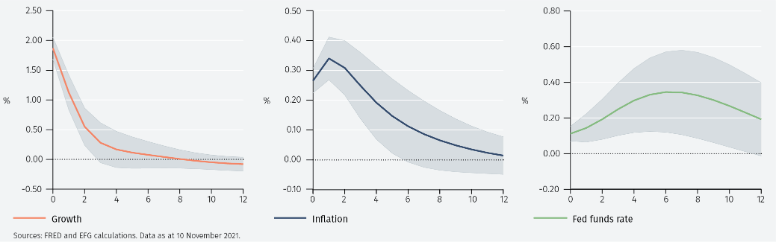

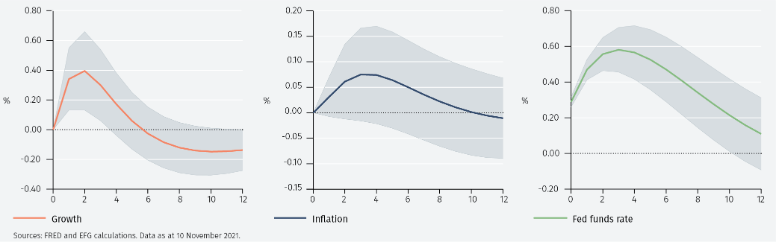

To illustrate how central banks’ responses to supply and demand disturbances differ, a simple model estimated on US data since 2000 is used.5

Figure 2 shows how real GDP growth, inflation and the Federal funds rate react to a contractionary aggregate supply shock While real GDP growth falls and inflation rises, there is no statistically significant change in the Federal funds rate. While weaker growth calls for lower interest rates, the rise in inflation calls for higher rates. Thus, the policy implication of the changes in growth and inflation offset each other.

Figure 3 shows that real GDP growth and inflation both rise in response to an expansionary demand shock, leading the Fed to raise interest rates.

Figure 4 shows the effects of unexpected increases in interest rates. These appear to happen in advance of the increase in real GDP growth. This finding is typically interpreted as evidence that the Fed raises interest rates as its analysis shows that growth is about to pick up.6

Conclusions

A growing number of commentators feel that developed countries’ central banks are “falling behind the curve” by not raising interest rates in response to surging inflation. But that seems to disregard the fact that the current rise in inflation is largely due to bottlenecks and other supply considerations, that at least the Fed has not responded to in the past.

Furthermore, and as central banks have noted repeatedly, they still think that the increase in inflation is temporary. If they are right, tighter monetary policy today would slow inflation a few years out when it may otherwise have returned to central banks’ objectives.

To download the full article, please use the button below.

1 See John B. Taylor, Discretion versus policy rules in practice, Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 39 (1993) 195-214. Taylor measured inflation using the change in the GDP deflator over four quarters and assumed that the neutral real interest rate was 2%. The output gap used by Taylor was the percent difference between trend and actual real GDP.

2 See https://fred.stlouisfed.org/

3 The Fed and the ECB have now one more reason not to react immediately to rising inflation: the symmetry of their mandates and their willingness to tolerate inflation above target to compensate for past below-target inflation.

4 The neutral real interest rate is defined as the real interest rates that would be appropriate for the central bank to achieve if inflation is at target and the cyclical state of the economy is at neutral.

5 A VAR(2) model is estimated on data on real GDP growth, inflation as measured by the GDP deflator (both over four quarters) and the Federal funds rate for 2000Q1-2021Q3. The identify restrictions are that (a) while aggregate demand shocks determine nominal GDP growth, aggregate supply factors determine how that is split up into real GDP growth and inflation; and (b) that monetary policy shocks have no immediate impact on growth and inflation.

6 Since the results are symmetric (by assumption), the findings are also compatible with the idea that the Fed cuts interest rates when it expects growth to slow.

Important Information

The value of investments and the income derived from them can fall as well as rise, and past performance is no indicator of future performance. Investment products may be subject to investment risks involving, but not limited to, possible loss of all or part of the principal invested.

This document does not constitute and shall not be construed as a prospectus, advertisement, public offering or placement of, nor a recommendation to buy, sell, hold or solicit, any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. It is not intended to be a final representation of the terms and conditions of any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. This document is for general information only and is not intended as investment advice or any other specific recommendation as to any particular course of action or inaction. The information in this document does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of the recipient. You should seek your own professional advice suitable to your particular circumstances prior to making any investment or if you are in doubt as to the information in this document.

Although information in this document has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no member of the EFG group represents or warrants its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Any opinions in this document are subject to change without notice. This document may contain personal opinions which do not necessarily reflect the position of any member of the EFG group. To the fullest extent permissible by law, no member of the EFG group shall be responsible for the consequences of any errors or omissions herein, or reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein, and each member of the EFG group expressly disclaims any liability, including (without limitation) liability for incidental or consequential damages, arising from the same or resulting from any action or inaction on the part of the recipient in reliance on this document.

The availability of this document in any jurisdiction or country may be contrary to local law or regulation and persons who come into possession of this document should inform themselves of and observe any restrictions. This document may not be reproduced, disclosed or distributed (in whole or in part) to any other person without prior written permission from an authorised member of the EFG group.

This document has been produced by EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited for use by the EFG group and the worldwide subsidiaries and affiliates within the EFG group. EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority, registered no. 7389746. Registered address: EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited, Leconfield House, Curzon Street, London W1J 5JB, United Kingdom, telephone +44 (0)20 7491 9111.