- Date:

Insight - Concerns about China will overshadow global growth prospects in the rest of the year. Around the world, however, massive infrastructure spending is needed for a sustainable post-pandemic recovery.

OVERVIEW

Concerns about China will overshadow global growth prospects in the rest of the year. Around the world, however, massive infrastructure spending is needed for a sustainable post-pandemic recovery.

From Sputnik and ‘Japan as Number One’ to China today

In 1961, as Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first man to orbit Earth, Nobel prizewinning economist Paul Samuelson predicted that the Soviet Union would overtake the US to become the world’s largest economy. Its economy was only half the size of the US at the time, but Russia’s superior technology and its planned economy (considered a benefit at the time) meant it would overtake the US as soon as 1984, Samuelson thought. That didn’t happen. Today, Russia’s GDP is only a fifth of that of the US (even at purchasing power parity, a measure which boosts the Russian level); its GDP per capita is less than half the US level.

In 1979, Harvard professor Ezra Vogel predicted in his book Japan as Number One, that Japan would overtake the US in terms of GDP per capita by 1985 and in overall GDP by 1998. That didn’t happen either. Today, Japan’s GDP per capita is two thirds of the US level and its overall GDP around one quarter of the US.

Starting in the early 2000s, many predicted China would soon overtake the US. Indeed, in our own EFGAM 2014 Outlook publication, we argued that China’s GDP would, at purchasing power parity, overtake the US by 2020. That did happen. Today, China is 20% bigger than the US on that measure although GDP per capita is only around a quarter of the US level. But, quite suddenly, concerns about China’s growth model have arisen and intensified. Could it be another Russia or Japan?

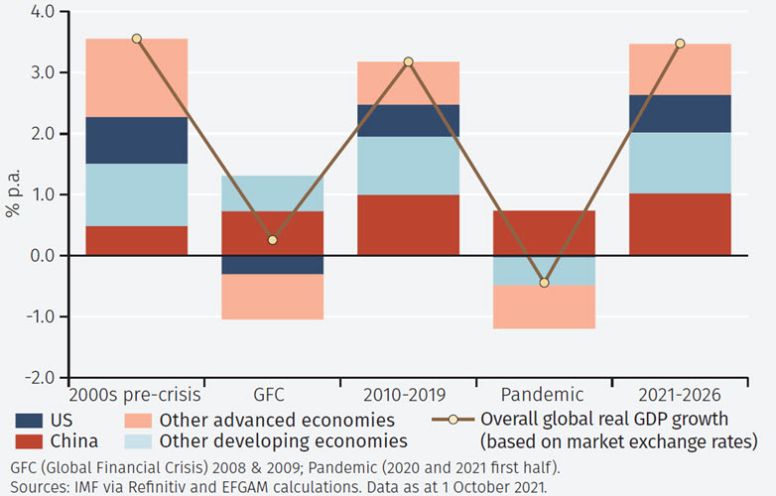

The IMF’s latest predictions are that it will not. China will grow at an average rate of 5% p.a. in real terms in the next five years (lower than the 8% average of 2010-2019). That implies it will still make one of the largest contributions to global economic growth (see Figure 1). Indeed, on the IMF’s forecasts the pattern of world growth (that is, split between the US and China and other emerging and developed countries) will be similar to that which followed the global financial crisis.

Not a ‘Lehman moment’ for China

The robustness of China’s growth has been questioned for many years. One of its main vulnerabilities – the importance of a credit-fuelled residential property sector (see Asia section on page 9) – has recently come into sharp focus. But we doubt this will be China’s ‘Lehman moment’: that is, a dislocation which threatens not just the Chinese, but the global financial system and economy. The main reason is that China’s predominantly state-controlled banks are likely to facilitate a restructuring of property-related debt with some form of government assistance.

However, there are other concerns. The way in which the government has curbed activities such as online tutoring and gaming raises questions about what might be next. And various interpretations of what is meant by the new approach of “common prosperity” are clearly possible.

A post-pandemic infrastructure

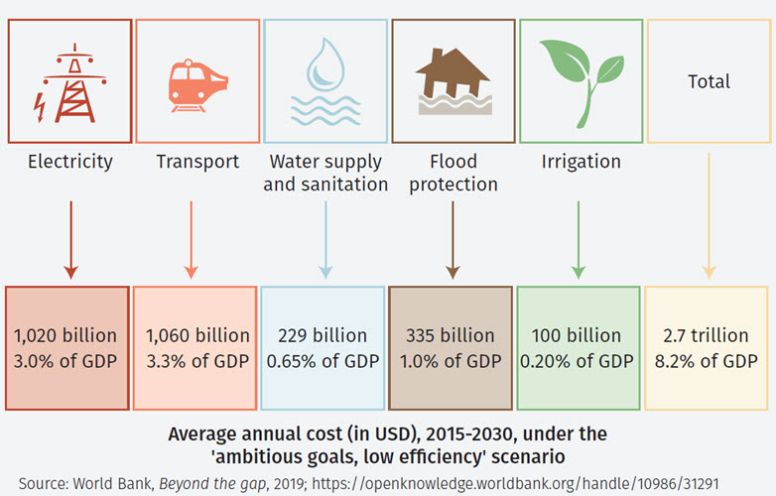

Despite these China concerns, other factors clearly support global growth. The World Bank estimated, pre-Covid, that the investment needs of emerging economies to meet climate change and sustainable development goals could amount to more than US$3 trillion per year (see Figure 2). Given the disruption caused by Covid, that annual amount is now even higher. In a similar vein, Mark Carney has estimated that global new energy infrastructure spending to meet net zero objectives (for advanced and emerging economies together) could be up to US$2.5 trillion a year.1

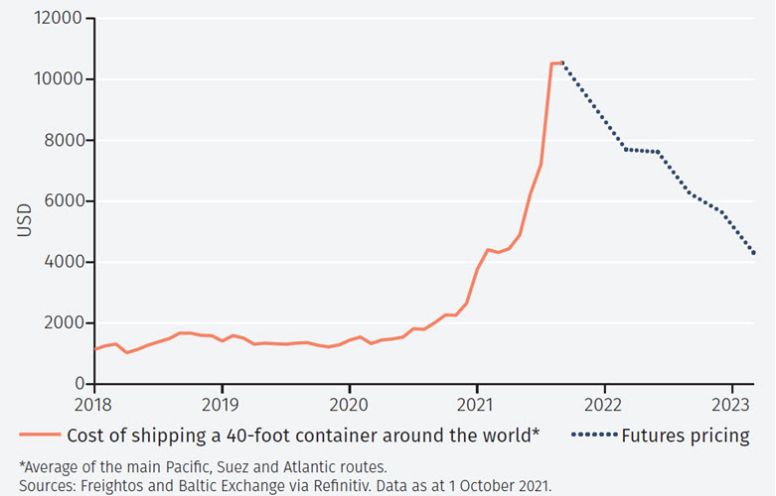

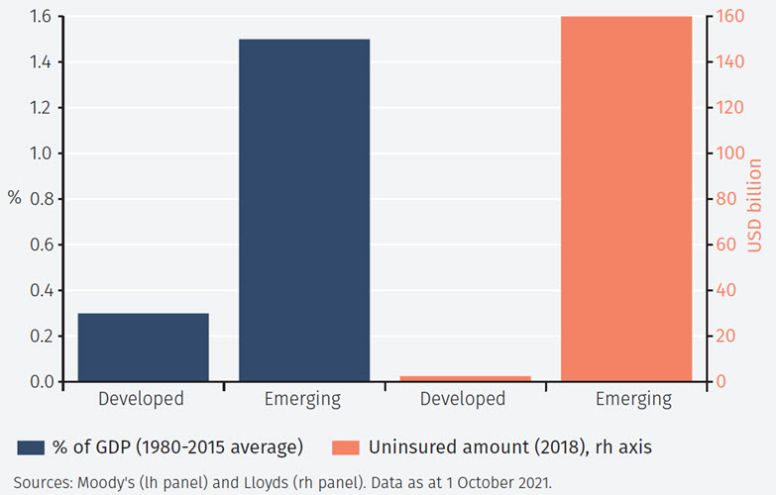

Such huge spending requirements may seem daunting, especially in a world still mired in the difficulties of postCovid recovery: supply chain disruptions, higher freight costs (see Figure 3), shortages of many key industrial components and, as a result of these changes, higher inflation. The world’s focus is, however, changing. The growing frequency of natural disasters, the consequences of which are often uninsured, and their particularly large effect on emerging economies (see Figure 4), are driving the need for much improved infrastructure.

Some will argue that such plans are unaffordable, but with low borrowing costs – even for very long periods – still in place and likely to remain so, that argument does not seem very well founded (see Special Focus on page 11).

Corporate profitability

It would be unreasonable to expect the building of the new global infrastructure to be a job of governments alone. Indeed, the finances of many governments are already stretched as a result of the cost of Covid. The private sector around the world will clearly need to play an important role. There are grounds for optimism that it will rise to the challenge. First, in many respects it is the corporate sector that is taking the lead in new technologies to address climate change and improve sustainability: electric vehicles, solar and wind power, big data and other new technologies may be helped by government support but are largely products of private enterprise.

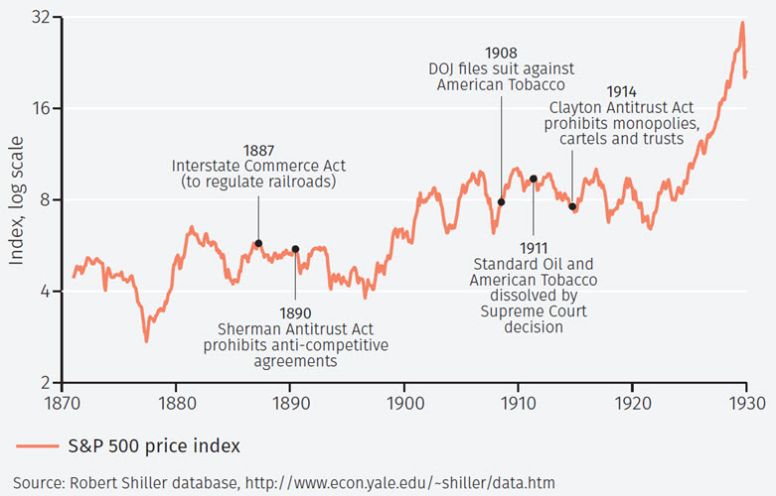

Second, corporate profit margins are high and, we think, will be maintained (see Figure 5), meaning companies have the ability to finance new investment spending. One concern raised by high profitability is, of course, that it may reflect anti-competitive practices. Greater regulation may be inevitable. But as far as the equity market is concerned, history suggests that may be no bad thing.

During the US Gilded Age (from around 1870 to the late 1890s) the US experienced a massive economic transformation, but many markets were characterised by monopolies. These may have been to the benefit of individual firms, but not for the broader economy and the S&P 500 index was essentially flat in that period (see Figure 6). The Gilded Age was followed by the Progressive Era, and a shift toward government regulation of business to ensure competition and free enterprise. Stock prices rose sharply during this period – an encouraging lesson for today’s times.

To continue reading, please use the button below to download the full article.

Footnotes

1 In a Bloomberg Television interview on 23 September 2021.

Important Information

The value of investments and the income derived from them can fall as well as rise, and past performance is no indicator of future performance. Investment products may be subject to investment risks involving, but not limited to, possible loss of all or part of the principal invested.

This document does not constitute and shall not be construed as a prospectus, advertisement, public offering or placement of, nor a recommendation to buy, sell, hold or solicit, any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. It is not intended to be a final representation of the terms and conditions of any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. This document is for general information only and is not intended as investment advice or any other specific recommendation as to any particular course of action or inaction. The information in this document does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of the recipient. You should seek your own professional advice suitable to your particular circumstances prior to making any investment or if you are in doubt as to the information in this document.

Although information in this document has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no member of the EFG group represents or warrants its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Any opinions in this document are subject to change without notice. This document may contain personal opinions which do not necessarily reflect the position of any member of the EFG group. To the fullest extent permissible by law, no member of the EFG group shall be responsible for the consequences of any errors or omissions herein, or reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein, and each member of the EFG group expressly disclaims any liability, including (without limitation) liability for incidental or consequential damages, arising from the same or resulting from any action or inaction on the part of the recipient in reliance on this document.

The availability of this document in any jurisdiction or country may be contrary to local law or regulation and persons who come into possession of this document should inform themselves of and observe any restrictions. This document may not be reproduced, disclosed or distributed (in whole or in part) to any other person without prior written permission from an authorised member of the EFG group.

This document has been produced by EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited for use by the EFG group and the worldwide subsidiaries and affiliates within the EFG group. EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority, registered no. 7389746. Registered address: EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited, Leconfield House, Curzon Street, London W1J 5JB, United Kingdom, telephone +44 (0)20 7491 9111.