- Date:

Latin America has been severely impacted by Covid-19, with an expected decline in GDP of over 8.5% in 2020, according to IMF estimates. However, responses to the crisis have varied across countries in the region. In this edition of Infocus, Joaquin Thul looks at three Andean countries – Chile, Colombia and Peru – and examines their responses and the economic impact of the pandemic.

Economic overview

As with most parts of the world, the peak in economic pain this year was experienced in the second quarter. In year-on-year terms, in the second quarter Chilean GDP contracted by 13.7%, Colombian GDP by 15.5% and Peru’s GDP by over 30%. Since then activity has rebounded but, for 2020 as a whole, growth prospects differ significantly among Latin American economies. Peru and Ecuador are expected to suffer double-digit declines in activity, while Chile and Colombia are expected to experience milder contractions of around 6% and 8%, respectively (see Figure 1). All countries are expected to see a further recovery in GDP next year.

In addition to the challenges posed by Covid-19, the regio nwas negatively affected by falling commodity prices, includin oil and copper. The decline in Chinese demand for oil in Q1 and the supply issues in the OPEC+ group of countries caused oil prices to fall to historical lows. Similarly, the decline in copper demand due to the coronavirus crisis pushed its price down to USD 209 per metric tonne in March from USD 280 per metric tonne in January. This affected finances in Chile and Peru, the world’s largest copper producers. According to Chile’s Mining Minister, every cent of a dollar decline in the copper price represents a loss of revenue of USD 60 million for the Chilean government and a drop of USD 125 million in the value of exports for the country.1

The extraordinary monetary and fiscal support deployed across the world was key in mitigating the negative impact on employment and private sector incomes. However, this was not true for all Latin American countries given domestic market conditions and budget constraints. Only those with low inflation rates and a strong domestic currency market have been able to lower interest rates. At the same time, only those countries with enough fiscal space have been able to engage in expansive fiscal policies.

Monetary policy measures

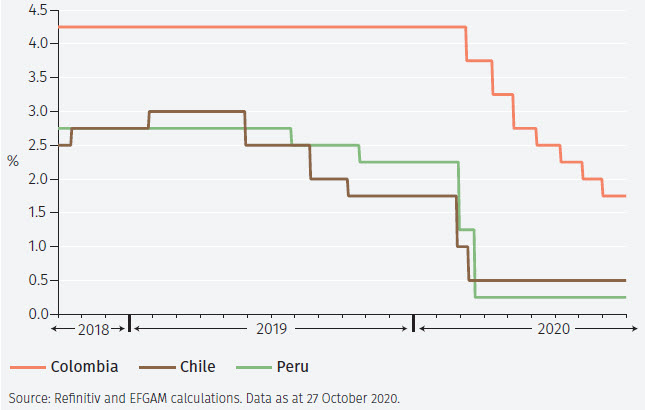

In Colombia, the central bank acted swiftly to protect the economy and implemented measures including interest rate cuts, liquidity and credit facilities to domestic firms and, for the first time, quantitative easing (QE). The central bank cut interest rates seven times between March and October, reducing the policy rate to 1.75% in October from 4.25% in February.

To contain the rise in government bond yields, Colombia’s central bank announced it would engage in QE, becoming the first Latin American country to use this monetary policy tool. The first round of QE included the purchase of up to approximately USD 2.6 billion in government bonds. As a result, 10-year government bond yields which had increased from 5.5% in January to 9% in March, fell by 50 basis points in the following days and gradually converged to 5% by September.

At the start of 2020 Chile had the lowest interest rates in the region – the Chilean central bank had cut rates three times in 2019, from 3% to 1.75% (see Figure 2). Following the Covid-19 outbreak, the monetary policy committee cut rates twice by 75bps and 50bps in March and April respectively, bringing the interest rate down to 0.50%. With rates already close to the zero lower bound and following Colombia’s example, in June the Chilean central bank announced the implementation of QE policies launching an asset purchase program of up to USD 8 billion over the following six months.

In Peru, the central bank had cut interest rates twice in 2019. At the start of the pandemic Peru’s inflation rate was already slightly below 2%. This allowed the central bank to act swiftly after the outbreak, providing the necessary stimulus by implementing two more rate cuts in March and April, of 100bps each, bringing the reference rate to 0.25% (see Figure 1). The central bank also cut reserve requirements for commercial banks and offered a series of new liquidity and guarantees facilities for the corporate sector.

Fiscal policy measures

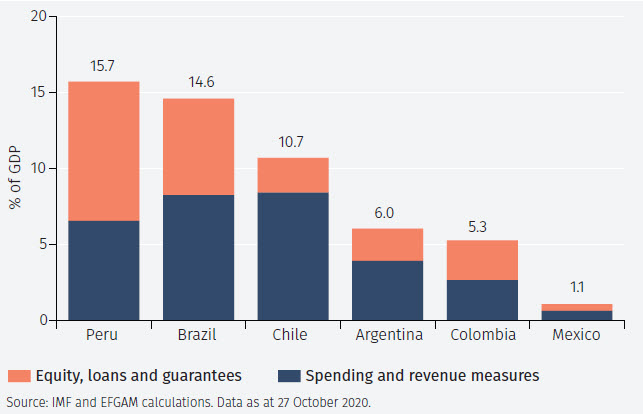

On the fiscal front, the three countries followed a similar approach. According to IMF estimates, Peru is among the countries providing the most fiscal support; its package is worth more than 15% of GDP and includes spending measures, equity, loans and guarantees. The fiscal packages in Chile and Colombia account for 10.7% and 5.3% of GDP

respectively (see Figure 3).

At the start of 2020, Chile and Peru had relatively low financing costs and debt-to-GDP ratios of 28% and 27% respectively. This provided space for both governments to increase debt, without endangering its long-term sustainability. By the end of the year, debt-to-GDP ratios are expected to reach 33% and 40% in Chile and Peru, respectively.

The limited fiscal support deployed in Colombia can be attributed to the worsening of economic conditions in recent years. By the end of 2019, gross debt had escalated to 50% of GDP, the current account deficit exceeded 4% of GDP, while the

fiscal deficit was around 2.5% of GDP. Additionally, the lower government revenue as a result of declining economic activity and weak oil prices hindered the ability of the Colombian government to provide further support.

Other policy measures

Peru and Chile have also allowed people to withdraw up to 25% and 10% of their private pension funds (AFPs) respectively. This has boosted disposable incomes by allowing workers to access their retirement savings and has not required any additional government spending. A similar project is under consideration in the Colombian congress.

According to one of Peru’s largest AFPs, the total withdrawals since April have amounted to approximately USD 5 billion, or 13% of total private pension funds’ assets.2 In Chile, during the first month following the constitutional amendment,93% of AFP clients had withdrawn a portion of their savings. According to the Chilean central bank, to the end of August workers had withdrawn USD 15.3 billion, more than 75% of the potential withdrawal limit and equal to 6% of Chile’s GDP.3

Conclusions

The rebound in commodity prices from the first quarte rlows will provide a boost to Andean countries‘ exports. The recovery in the copper price will favour a recovery in the industrial sectors of Chile and Peru which, combined with the recent pick-up in domestic consumption, should contribute to improved growth prospects for the remainder of 2020. Following a contraction of GDP of 6% in 2020, Chile is expected to grow by 4.5% in 2021.

On 25 October 2020, Chile held a referendum to establish a new constitution, following the social protests that erupted in the final quarter of 2019. The referendum was approved with almost 80% of support and will mandate an elected assembly to write a new constitution. The process is due to take a couple of years and is likely to open the discussion for deep economic reforms in the country. This will add uncertainty to Chile’s outlook in the coming years and could hinder its economic recovery.

Although the IMF anticipates GDP growth in Peru of over 7% in 2021, the recovery remains contingent on how quickly the government can reactivate an economy suffering a double digit contraction in 2020. The focus will turn to reducing the unemployment rate which increased from 6% in March to 16% in August.

In Colombia, despite the large monetary stimulus, fiscal support has been limited due to the weaker economic fundamentals at the start of the year. According to IMF projections, this will translate into GDP growth of 4% next year, above the 3.3% average expected for Latin America but below that for Chile and Peru.

With inflation around 2% in the three economies, monetary policy is likely to remain accommodative for the time being. Despite the depreciation of the Andean currencies against the US dollar in 2020, central banks expect the pass-through into broad inflation to be limited.

Overall, the measures implemented to mitigate the effects of the Covid-19 crisis are likely to come at a cost of larger fiscal deficits, higher debt levels and future funding problems for the pension systems. However, in the context of a region severely hit by the pandemic, the Andean economies appear well positioned to benefit from a cyclical rebound.

Footnotes

1 ‘Desplome en el precio del cobre asesta un duro golpe al fisco chileno’, El Economista, Chile, 20 March 2020.

2 https://www.emol.com/noticias/Economia/2020/07/21/992644/retiro-fondos-pensiones-Peru.html

3 Informe de Política Monetaria, Banco Central de Chile, September 2020.