- Date:

The outcome of the upcoming German elections is uncertain. Many observers are concerned about who will succeed Angela Merkel after 16 years as German Chancellor and de facto leader of the European Union. In this edition of Infocus, GianLuigi Mandruzzato looks at the main issues at stake in the forthcoming German vote.

Less than two weeks before the German elections on 26 September, it is far from clear who will succeed Angela Merkel as Chancellor. Nevertheless, several key issues are clear. The first is that the next government will likely be supported by a three-party coalition, a first for post-war Germany. The second is that the fight against climate change and more investment in infrastructure will be at the top of the agenda, whatever the composition of the next government coalition. The third is that while there will be no drastic changes in fiscal policy and European integration, in both areas the approach of the next German government will be more proactive and flexible, which should be appreciated by the financial markets.

Who will be the next Chancellor?

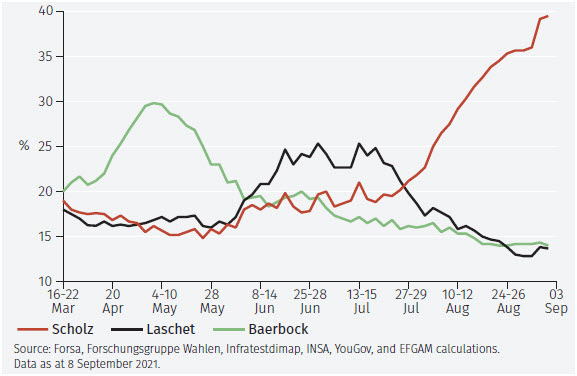

The German general election on 26 September will mark the end of Merkel’s Chancellorship after 16 years and the race for her successor remains wide open. The polls show the greatest support for the SPD’s Olaf Scholz. The popularity of Scholz, who is Vice-Chancellor and Finance Minister in the incumbent CDU/CSU-SPD coalition government, has soared since Germany was hit by heavy flooding in mid-July (see Figure 1). As Finance Minister, Scholz has been proactive in ensuring support for people and businesses affected by the floods, demonstrating to the voters his ability to manage a crisis.

In contrast, the CDU/CSU’s candidate Armin Laschet, the incumbent President of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany’s largest and most populous Länder, was criticised for some inappropriate behaviour at a memorial for flood victims and for the slow pace of his government in North Rhine-Westphalia in distributing financial support to those affected by the floods. The decline in Laschet’s popularity is seen by many as the main reason for the decline in support for the CDU/CSU.

The Green’s candidate Annalena Baerbock has failed to capitalise on an event that demonstrates the urgency of the fight against climate change and has also been penalised for not having government experience.

If the polls are a good guide to the election results, Scholz is the most likely candidate to succeed Merkel as Chancellor, although this ultimately depends on the composition of the government.

Which government coalition?

According to German Basic Law, the Chancellor is elected by the Bundestag, Germany’s lower house, on the advice of the Federal President of the Republic. Members of the Bundestag are elected according to a proportional representation system with a 5% barrier. If no party obtains an absolute majority of seats, the party with the greatest support is asked to consult with the other parties to form a coalition government. However, other coalitions that would exclude the party with the most seats in the Bundestag are also possible. When a coalition controlling a majority of seats in the Bundestag is agreed, the parties report the outcome of the consultations to the President of the Republic, including the name of the Chancellor candidate, who then appears before the Bundestag to seek approval to govern.1

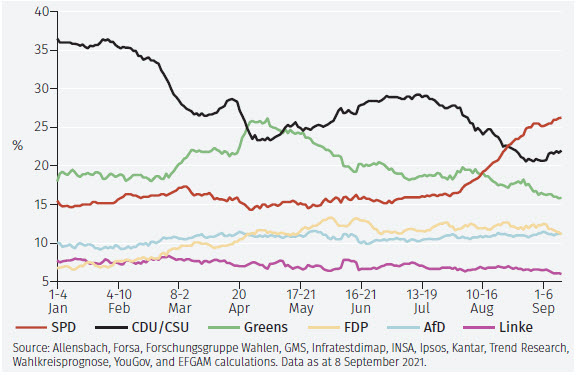

With less than two weeks left before the vote, the polls (see Figure 2) suggest that:

- no party will win an absolute majority in the Bundestag, hence the next government will most likely be supported by a coalition;

- the centre-left SPD is leading and its momentum has been rising since the floods that hit Germany around mid-July;

- the support for Merkel’s centre-right CDU/CSU has stumbled to an historical low;

- the Green party has lost support since the spring and now trails the other two major parties;

- support for the other parties that will likely enter the Bundestag has stabilised at 12% for the liberals of the FDP, at 11% for the far-right AfD, and at 7% for the leftist Die Linke.

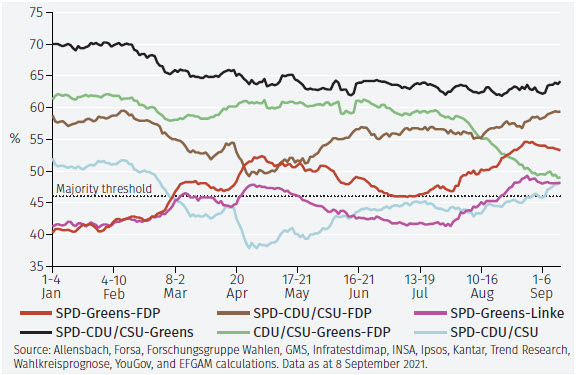

If the election result is in line with the polls, for the first time in the post-war period the government coalition could include three parties. In theory, this opens up numerous alternative formations, but only a few of them are viable because all of the four largest parties have effectively ruled out governing with either the AfD or Die Linke.

Although negotiations for the formation of the new government will probably be long and complicated, the good news for markets is that the coalition including the SPD, the Greens, and the FDP, known as the traffic light coalition after the colours of the three parties, seems by far the most likely (see Figure 3)2. One point of uncertainty relates to whether the FDP is willing to govern with the Greens. In 2017, the FDP abandoned consultations for a possible CDU/CSU-Greens-FDP coalition arguing that the Greens’ positions on taxation and public spending were incompatible with its electoral base. That decision, which was followed by six months of gruelling negotiations between the CDU/CSU and the SPD to create the incumbent Grosse Koalition, reduced the FDP’s popularity towards the 5% critical threshold. It therefore seems unlikely that the FDP will make the same choice today, at the risk of paying an even higher price and given the increased profile of environmental issues in German politics.

What will be the priorities of the next government?

Agreement among the SPD, the Greens, and the FDP can be found on greater public investment in environmental policies, innovation and the improvement of infrastructure. At the same time, the presence of the FDP in government would be welcomed by the markets as a guarantee against a generalised increase in taxation and regulation, including of the labour and housing markets.

It might be more complicated to find a common denominator in the approach to the European Union. The SPD and the Greens favour greater European integration, including an increase in the EU budget and the development of fiscal solidarity instruments. In contrast, the FDP has historically held rigid positions on burden sharing within the EU and respect of fiscal sustainability criteria. The leadership of Scholz, who is a committed pro-European and an enthusiastic supporter of the Recovery and Resilience Fund as a first step towards European fiscal union, will immediately be tested in this area.

However, no drastic changes in German economic policy would be expected. Besides the broad-based composition of the next government coalition, which will most likely include parties from both political sides, the scope for major change is limited by the need to find agreement with the opposition on major issues. This is because the German Constitution grants the opposition parties a de-facto veto power on issues that also need the approval of the Bundesrat, the German Upper House whose members reflect the results of regional elections.

Conclusions

With less than two weeks before the vote that will mark the end of the Merkel era, it is still uncertain who will succeed her as Chancellor. The SPD, the party of incumbent Vice- Chancellor and Finance Minister Scholz, is leading in the polls but rapid changes in voters’ opinions cannot be ruled out.

If the polls are a good guide to the elections, the next German government will for the first time in the post-war period be supported by a three-party coalition. This presents the risk that the consultations for the formation of the government will once again take a long time and that government action itself will be less decisive and effective. However, the most likely coalition, led by the SPD together with the Greens and the liberals of the FDP, would easily agree on more public investment to fight climate change and improve German infrastructure. The new government is expected to be moderately more proactive on fiscal and European policies than under Chancellor Merkel, while moving in continuity with her actions. Overall, such an election outcome would likely be viewed positively by financial markets.

1 Article 63, commas 3 and 4, of the German Basic Law prescribes that if the Chancellor candidate is not voted by an absolute majority of the Bundestag members, other candidates can be proposed. If within 14 days, no candidate receives an absolute majority, the Bundestag can elect a new Chancellor by a simple majority. Within seven days from the election, the Federal President may appoint the new Chancellor, allowing the formation of a minority government, or dissolve the Bundestag and call new elections within 60 days.

2 Other mathematically possible coalitions are, however, hardly feasible. The Greens are unlikely to agree to be the junior partner in a coalition led by CDU/CSU and complemented by the FDP. It seems also unlikely, although not impossible, that the CDU/CSU would agree to be part of an SPD-led coalition together with the Greens. Likewise, the SPD would have little interest in enlarging the Grosse Koalition to the FDP since it would rather choose a more like-minded partner such as the Greens. Finally, another Grosse Koalition with reversed roles between SPD as leader and CDU/CSU as junior partner can no longer be excluded.

Important Information

The value of investments and the income derived from them can fall as well as rise, and past performance is no indicator of future performance. Investment products may be subject to investment risks involving, but not limited to, possible loss of all or part of the principal invested.

This document does not constitute and shall not be construed as a prospectus, advertisement, public offering or placement of, nor a recommendation to buy, sell, hold or solicit, any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. It is not intended to be a final representation of the terms and conditions of any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. This document is for general information only and is not intended as investment advice or any other specific recommendation as to any particular course of action or inaction. The information in this document does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of the recipient. You should seek your own professional advice suitable to your particular circumstances prior to making any investment or if you are in doubt as to the information in this document.

Although information in this document has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no member of the EFG group represents or warrants its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Any opinions in this document are subject to change without notice. This document may contain personal opinions which do not necessarily reflect the position of any member of the EFG group. To the fullest extent permissible by law, no member of the EFG group shall be responsible for the consequences of any errors or omissions herein, or reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein, and each member of the EFG group expressly disclaims any liability, including (without limitation) liability for incidental or consequential damages, arising from the same or resulting from any action or inaction on the part of the recipient in reliance on this document.

The availability of this document in any jurisdiction or country may be contrary to local law or regulation and persons who come into possession of this document should inform themselves of and observe any restrictions. This document may not be reproduced, disclosed or distributed (in whole or in part) to any other person without prior written permission from an authorised member of the EFG group.

This document has been produced by EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited for use by the EFG group and the worldwide subsidiaries and affiliates within the EFG group. EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority, registered no. 7389746. Registered address: EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited, Leconfield House, Curzon Street, London W1J 5JB, United Kingdom, telephone +44 (0)20 7491 9111.