- Date:

Infocus - China’s economic growth slowed in 2021, raising doubts about the sustainability of the global recovery from Covid-19. Many observers fear the renminbi will depreciate – mirroring what often happens in struggling emerging countries.

China’s economic growth slowed in 2021, raising doubts about the sustainability of the global recovery from Covid-19. Many observers fear the renminbi will depreciate – mirroring what often happens in struggling emerging countries. In this edition of Infocus, Daisy Li and GianLuigi Mandruzzato examine the outlook for China’s growth and its currency.

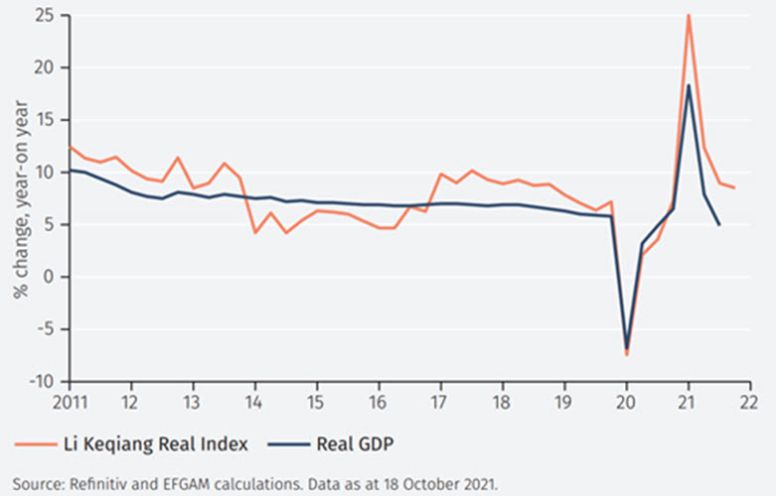

The Chinese economy has recently lost momentum as shown by a wide range of indicators, including retail sales, industrial production and PMI indices. The Li Keqiang index, a synthetic measure often used to estimate Chinese GDP growth, indicates a marked decline in Q3 and into Q4 (see Figure 1).1 In the first three quarters of 2021, Chinese GDP growth fell to an average rate of only 0.5% quarter-on-quarter. This is equivalent to 2% annualised growth, below the estimated potential growth rate of around 5.5%.2 It is interesting to note that after the fluctuations due to the Covid-19 pandemic, Chinese GDP is returning to the trend of moderately slowing growth that has been underway for several years.

How to interpret China’s slowdown?

The slowdown in Chinese GDP growth leads to two observations. The first is that it reflects structural aspects of China’s development. As the Chinese economy is modernising and maturing, the service sector, which is naturally slowgrowing, becomes an increasingly important share of the economy, reducing the overall growth rate.3

The second observation is that the intensity of the most recent slowdown raises concerns about the world economy because of the size of China. It is either the first or second largest economy in the world, depending on how GDP is measured, and it has made the highest contribution to global GDP growth over the last two decades. Markets often assume that the Chinese government is perfectly able to manage policy so that growth remains on a stable path. That indeed was the case until the Covid crisis. However, managing an increasingly large and complex economy was always likely to be difficult.

The policy measures introduced recently, although leading to slower growth, have arguably put economic growth on a more sustainable path.

These have included strict anti-Covid policies and tightening of regulation on sectors such as internet-based services, private education, real estate and those characterised by high CO2 emissions.

For example, tighter regulation imposed on internetrelated activities, a sector deemed strategic by the Chinese authorities, has increased uncertainty among internet operators and, unsurprisingly, contributed to the moderation in fixed asset investment. Similarly, the emphasis on reducing greenhouse gas emissions has led state owned banks to tighten the provision of finance to highly polluting sectors, curbing production as in the case of steel.

The real estate sector is also subject to restrictive measures aimed at limiting its chronic excesses. This is nothing new: in recent years, the trend in construction financing has been weaker and more volatile than that of total loans (see Figure 2). In a banking market dominated by public institutions, this trend reflects government guidance.4

Limited impact on the exchange rate

Faced with the slowdown in activity, many observers expect the Chinese government to facilitate a depreciation of the exchange rate to support the economy.5 However, there are several reasons to believe that the Chinese authorities will not do so at the current juncture. The internationalisation of the renminbi, including the ambition for it to compete with the US dollar and the euro as a reserve currency, is a strategic objective. In addition, the domestic bond market is opening to international investors, who have so far shown great interest. To achieve both objectives, it is preferable for the exchange rate to remain stable.6

Moreover, an opportunistic devaluation of the yuan would be frowned upon by Washington, which in the past has often complained about Beijing’s exchange rate policy. Now that the Biden administration has adopted a more conciliatory approach, the Chinese government has no interest in risking ratcheting up tensions again.

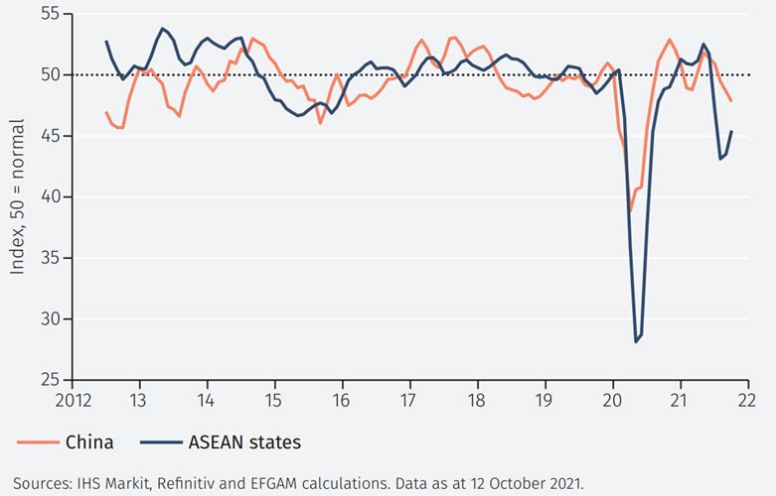

In policy terms, a weak renminbi would also make little sense. Foreign demand for Chinese products is benefiting from production bottlenecks caused by Covid in ASEAN states (see Figure 3). Furthermore, the slowdown is driven by domestic sectors, insensitive to the exchange rate. Rather, a strong yuan aids domestic demand by limiting imported inflation, supporting real incomes and allowing the PBOC to remain accommodative.

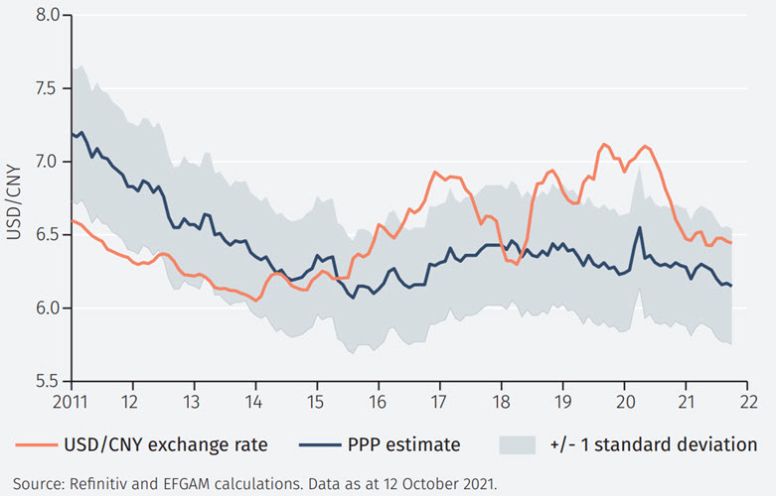

Finally, Purchasing Power Parity estimates suggest that the renminbi should be stronger vis-à-vis the US dollar, which would correspond to a lower USD/CNY exchange rate (see Figure 4). Furthermore, based on our PPP model, the USD/ CNY equilibrium exchange rate tends to fall over time, which means that keeping the renminbi stable increases its undervaluation and thus moderately supports the economy.7

Conclusions

The recent decline in Chinese growth is a source of concern for investors. However, it is the result of a mix of structural and cyclical factors. The former reflect the strong economic development of the last decades and the fact that the economy is maturing: as such, this is not a reason for concern. The latter relate to government policies adopted to strengthen long-term economic and financial stability which have led to an over-reaction by economic agents: while the degree of cyclical slowdown justifies the market’s worries in the short-term, it should eventually be transitory.

In this context, it seems unlikely that the Chinese authorities will again weaken the yuan to boost activity. The stability of the exchange rate meets the strategic objective of increasing its use in international trade and making it attractive as a reserve currency. Moreover, a weaker exchange rate would be ineffective in counteracting shocks affecting the domestic sectors of the economy. Finally, the fundamentals indicate that the yuan’s equilibrium exchange rate continues to rise: a stable exchange rate would be sufficient to provide moderate support for Chinese growth without compromising the improved relationship with the United States since the advent of the Biden administration.

1 The Li Keqiang index is named after the current Premier of the People’s Republic of China who, according to media reports, in 2007 said freight traffic volumes, electricity consumption and total loans give a better gauge of Chinese activity trends than official GDP data. This version of the index is calculated as the weighted average of the annual changes in the three indicators with total loans deflated by the CPI to produce a real measure comparable to GDP.

2 See https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-03-26/china-s-central-bank-estimates-potential-growth-of-under-6?sref=5epPVx10.

3 The tendency for growth to slow as the service sector increases in size has been widely discussed from William Baumol (American Economic Review, 1967) onwards.

4 In recent weeks, tensions in the real estate market have come to the fore in the case of Evergrande, once a major player in the sector and now on the brink of default.

5 The incomplete liberalisation of Chinese capital movements allows the People’s Bank of China to control the exchange rate of the yuan against other currencies.

6 For the same reason, it is likely that the Chinese authorities will intervene to prevent the Evergrande crisis from undermining the real estate sector and the Chinese bond market.

7 Other measures regarding the renminbi exchange rate cannot be excluded, although they look unlikely. Since the renminbi is a managed float against a basket of currencies, the authorities could change the basket in a way that results in devaluation. A more drastic alternative could be to simply abandon the basket and aggressively manage a currency depreciation. However, both alternatives would damage credibility and act against China’s aims to open up its capital account over time and reduce the attractiveness of the renminbi as a reserve currency.

Important Information

The value of investments and the income derived from them can fall as well as rise, and past performance is no indicator of future performance. Investment products may be subject to investment risks involving, but not limited to, possible loss of all or part of the principal invested.

This document does not constitute and shall not be construed as a prospectus, advertisement, public offering or placement of, nor a recommendation to buy, sell, hold or solicit, any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. It is not intended to be a final representation of the terms and conditions of any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. This document is for general information only and is not intended as investment advice or any other specific recommendation as to any particular course of action or inaction. The information in this document does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of the recipient. You should seek your own professional advice suitable to your particular circumstances prior to making any investment or if you are in doubt as to the information in this document.

Although information in this document has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no member of the EFG group represents or warrants its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Any opinions in this document are subject to change without notice. This document may contain personal opinions which do not necessarily reflect the position of any member of the EFG group. To the fullest extent permissible by law, no member of the EFG group shall be responsible for the consequences of any errors or omissions herein, or reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein, and each member of the EFG group expressly disclaims any liability, including (without limitation) liability for incidental or consequential damages, arising from the same or resulting from any action or inaction on the part of the recipient in reliance on this document.

The availability of this document in any jurisdiction or country may be contrary to local law or regulation and persons who come into possession of this document should inform themselves of and observe any restrictions. This document may not be reproduced, disclosed or distributed (in whole or in part) to any other person without prior written permission from an authorised member of the EFG group.

This document has been produced by EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited for use by the EFG group and the worldwide subsidiaries and affiliates within the EFG group. EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority, registered no. 7389746. Registered address: EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited, Leconfield House, Curzon Street, London W1J 5JB, United Kingdom, telephone +44 (0)20 7491 9111.