- Date:

With fiscal deficits surging but interest rates at unprecedently low levels, how concerned should investors be about government borrowing? In this edition of Infocus, EFG Chief Economist Stefan Gerlach looks at the issues involved.1

Public deficits are exploding as a consequence of the Covid-19 recession. With tax revenues imploding and governments engaging in large-scale stimulus programmes, many countries – including Canada, France, Italy, Japan, Spain the UK and the US – are expected to experience deficits of over 10% of GDP.2 With several of these countries already having large public debts, some commentators worry about the long-run prospects for public debt.

The sustainability of public debt is a particular concern in the eurozone since the ECB is not, at least not de jure, a lender of last resort to governments. In countries that have a domestic currency, such as the UK or the US, that concern is largely absent.

Some commentators argue that with 10-year government bond yields below 1% in most countries, and in some cases even negative, there is little reason for governments to worry about the cost of borrowing. Governments could safely run large deficits and lock in the current exceptionally low yields by selling long bonds. Of course, since governments typically do not pay back any borrowing but rather roll it over, this argument is slippery since the level of interest rates that will prevail when the bonds mature is unknown.

Fiscal dynamics

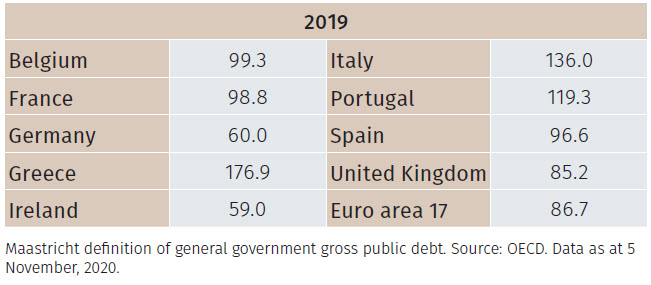

To think through these issues, it is useful to start by recalling that the size of the public debt in a country is generally compared to the country’s GDP (since taxes can be levied against it to service and repay the debt). Figure 1 shows debtto- GDP ratios at the end of 2019 for a number of eurozone countries, for the overall eurozone and for the UK. Debt-to- GDP ratios in the eurozone are often around 100%. In Greece, the debt ratio is almost 200%.

The evolution of the debt-to-GDP ratio depends on three factors:

• The interest cost of servicing the debt.

• The growth of GDP, which in turn depends on the rate of inflation and rate of real GDP growth.

• The primary fiscal deficit (that is, the deficit net of interest payments on the debt), expressed as a percentage of nominal GDP.

Using these factors, it is interesting to ask how large a primary deficit the government can run if it wishes to stabilise the debt-to-GDP ratio at its current level. That deficit is given by the difference between the interest rate on public debt and the growth rate of GDP, times the debt-to-GDP ratio.3 This spread plays a crucial role in debt sustainability analysis.

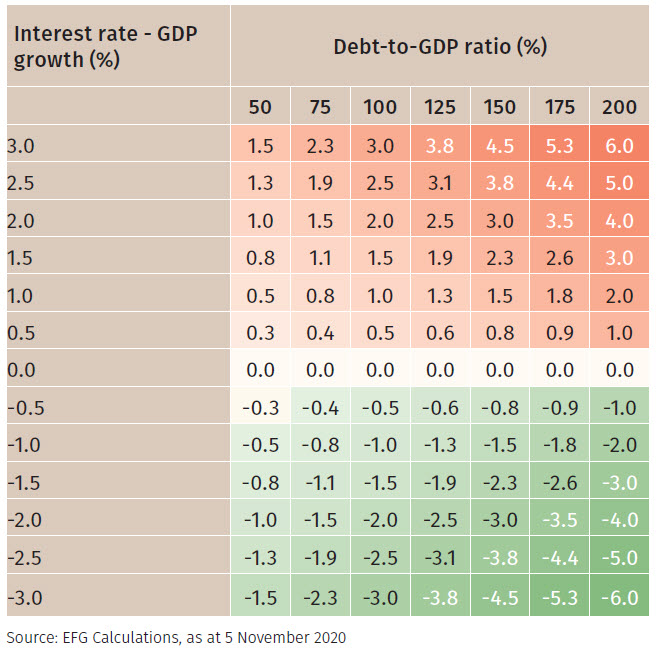

To see that, Figure 2 shows the necessary primary surplus depending on the spread between the interest rate and GDP growth for different assumptions regarding the debt-to-GDP ratio.

To understand Figure 2, suppose that the current debt-to-GDP ratio is 75% and that the interest rate on the debt is 0.5 percentage points higher than the growth rate of GDP. The table shows that in order to stabilise the debt-to-GDP ratio, the government must run a primary surplus of 0.4% of GDP forever. If the interest rate – GDP growth spread is 2%, then the necessary surplus is 1.5%.

The table leads to two important conclusions. First, it makes the point that high public debt, and interest rates exceeding the growth rate of GDP, require a larger primary surplus to stabilise the debt-to-GDP ratio.

Second, if interest rates are below the growth rate of GDP, it is possible for the government to stabilise the debt-to-GDP ratio while still running a primary deficit. Since this is the situation that is expected to prevail in a number of countries once the Covid-19 shock is overcome, it is not surprising that it is often argued that governments need not have any concerns about fiscal solvency.

However, in practice governments never pay back their debts but merely roll them over when they come due. While the interest rate – GDP spread looks attractive for the next few years, there is no guarantee that this situation will be permanent.

How large primary surpluses could governments run in emergencies?

The table raises the difficult question of how large a primary surplus could a government run for an extended period of time if a fiscal emergency arose. For instance, could Italy, whose debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to rise above 150% this year, run a permanent primary surplus of 2.3% that would be necessary if the interest paid on the public debt exceeded the growth rate of GDP by 1.5%?

It is a very difficult question to answer. To think about it, it is helpful to look at the size of primary surpluses countries have run in the past. Looking at the experiences of 34 OECD members over the period 2002-2019, three eurozone countries had a debt-to-GDP ratio of more than 100% in 2002: Belgium (105.4%), Greece (104.7%) and Italy (106.4%).

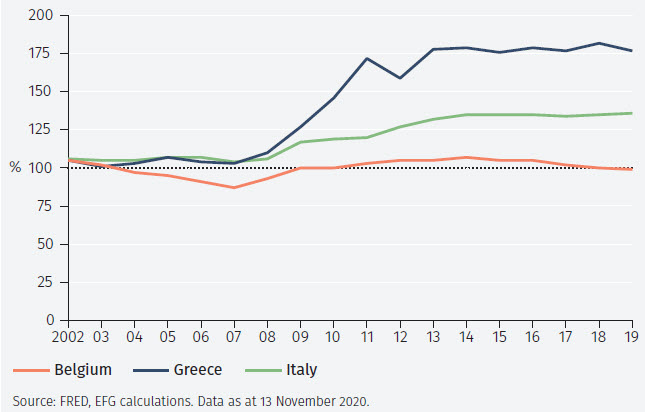

Figure 3 shows the primary balances of these countries and Figure 4 shows the evolution of their debt-to-GDP ratios. It is apparent that the countries took different approaches to their public debt.

The Belgian government strove to reduce their debt-to-GDP ratio before the 2009-2009 financial crisis, running primary surpluses of about 4% of GDP. That led to a decline in the debt-to-GDP ratio. During the financial crisis it ran small deficits and more recently has been running small surpluses. Overall, the debt-to-GDP ratio was 99.3% in 2019.

Italy displayed less discipline than Belgium and, except for 2009-10, ran consistently small surpluses in the period considered. As a consequence, the debt to GDP ratio rose to 136.0% in 2019.

Greece followed a third route by running primary deficits in the early 2000s. When the financial crisis hit, the deficits grew much larger, reaching about 10% of GDP in 2009 and 2013. As a part of its agreement with its official creditors, in 2016-2019, Greece ran large primary surpluses, averaging just below 4%. In 2019, the Greek debt-to-GDP ratio reached 176.9%, despite a debt restructuring intended to alleviate the burden of the debt.

The experiences of Belgium and Greece suggest that governments would find it difficult to run primary surpluses much larger than 4% on a sustained basis. The problem is largely political – a government that is willing to pursue such austerity to achieve a larger surplus is simply unlikely to be reelected. In terms of Figure 2, the five entries (i.e. those above 4%) in the upper right-hand corner are unlikely to be sustainable.

What is the average difference between the interest rate and GDP growth?

But what should governments assume regarding the average spread between the interest rate paid on the debt and the growth rate of GDP? While long term interest rates are currently exceptionally low, at times even negative, both they and GDP growth fluctuate over time. It seems hazardous to look only at current conditions when deciding whether to borrow, given that the loan will almost surely be rolled over indefinitely.

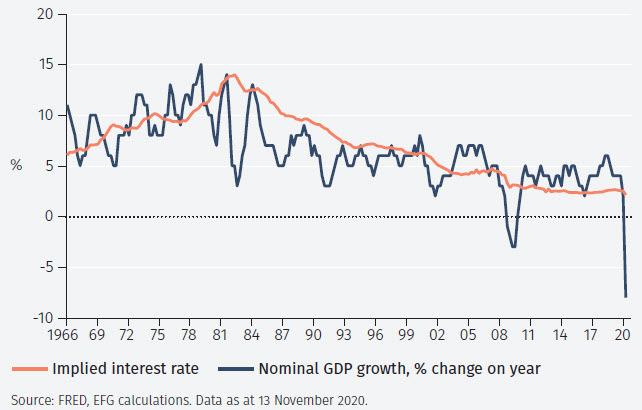

Governments borrow regularly at different interest rates of varying maturity. As a consequence, the interest paid on the public debt is an average of past borrowing rates. It therefore evolves slowly over time as the government engages in new borrowing. While the rate changes slowly, over extended periods of time it can change substantially.

As an illustration, Figure 5 shows the implied interest rate on the US public debt together with the growth rate of nominal GDP (over four quarters).4 Both series are rising from 1966 to around 1980, and decline subsequently. Importantly, while the interest rate changes slowly, GDP growth is subject to large fluctuations. GDP growth on occasions falls dramatically and even turns negative, implying that the debt-to-GDP ratio rises sharply. This is a major risk, in particular since episodes of unusually low GDP growth are often associated with large fiscal deficits.

In judging whether borrowing is a good idea, what difference between the interest rate and the growth rate of GDP should the government assume? In this specific sample, the interest rate exceeded GDP growth by on average 0.66%. However, since the global financial crisis in 2008-9, GDP growth has generally exceeded the interest rate.5 Thus, in this time period, the US government could have run a primary deficit and still stabilised the debt-to-GDP ratio. However, the figure also shows that between 1980-1999, the interest rate exceeded GDP growth by 2.68%, a very substantial amount.

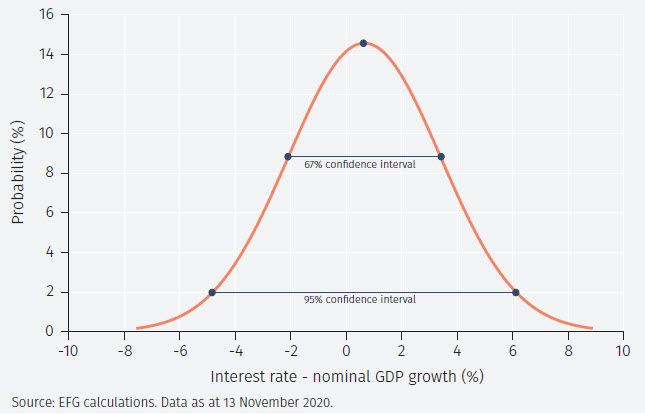

The spread is thus highly uncertain. Figure 6 shows just how uncertain it is. While the average difference is 0.66%, a 67% confidence band ranges from -2.08% to 3.39%; a 95% confidence band ranges from -4.82% to 6.13%. Plainly, history provides little guidance as to what spread to assume when borrowing.

Conclusions

With fiscal deficits surging but interest rates at unprecedently low levels, how concerned should investors be about government borrowing? The answer to that depends largely on the expected difference between the interest cost of new debt and GDP growth. These variables are both difficult to predict, GDP growth particularly so.

Of course, governments have little choice but to borrow to overcome the covid crisis. But while conditions are expected to be favourable for debtors in the next years, it would be hazardous to believe that this will be a permanent situation. History suggests that large and long-lasting spreads – positive or negative – between the interest cost of public debt and the growth of nominal GDP are possible. If the debt-to-GDP ratio is higher, say above 100%, this can quickly lead to a situation in which governments have to run large primary surpluses to prevent the debt-to-GDP ratio from rising further.

Footnotes

1 For related work, see ‘Fiscal Fortitude, Fiscal Folly and Fiscal Dominance’, Macro Flash Note 7 May 2020, by GianLuigi Mandruzzato and Daniel Murray; and ‘The long and winding road to eurozone debt sustainability’, InFocus May 19th 2020, by Grazia Cozzi and GianLuigi Mandruzzato.

2 See ‘Economic & financial indicators’, The Economist, p. 76, 31 October 2020,

3 This relationship is approximate; since GDP growth and interest rates fluctuate over time, their variances and covariance also matter. However, their effects are generally quite small and are disregarded here.

Important Information

The value of investments and the income derived from them can fall as well as rise, and past performance is no indicator of future performance. Investment products may be subject to investment risks involving, but not limited to, possible loss of all or part of the principal invested.

This document does not constitute and shall not be construed as a prospectus, advertisement, public offering or placement of, nor a recommendation to buy, sell, hold or solicit, any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. It is not intended to be a final representation of the terms and conditions of any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. This document is for general information only and is not intended as investment advice or any other specific recommendation as to any particular course of action or inaction. The information in this document does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of the recipient. You should seek your own professional advice suitable to your particular circumstances prior to making any investment or if you are in doubt as to the information in this document.

Although information in this document has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no member of the EFG group represents or warrants its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Any opinions in this document are subject to change without notice. This document may contain personal opinions which do not necessarily reflect the position of any member of the EFG group. To the fullest extent permissible by law, no member of the EFG group shall be responsible for the consequences of any errors or omissions herein, or reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein, and each member of the EFG group expressly disclaims any liability, including (without limitation) liability for incidental or consequential damages, arising from the same or resulting from any action or inaction on the part of the recipient in reliance on this document.

The availability of this document in any jurisdiction or country may be contrary to local law or regulation and persons who come into possession of this document should inform themselves of and observe any restrictions. This document may not be reproduced, disclosed or distributed (in whole or in part) to any other person without prior written permission from an authorised member of the EFG group.

This document has been produced by EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited for use by the EFG group and the worldwide subsidiaries and affiliates within the EFG group. EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority, registered no. 7389746. Registered address: EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited, Leconfield House, Curzon Street, London W1J 5JB, United Kingdom, telephone +44 (0)20 7491 9111.