- Date:

Insight - After one of the worst years for global economic growth in 2020, this year looks set to be one of the best. Indeed, the bounce in activity is greater than many expected just a few months ago.

OVERVIEW

After one of the worst years for global economic growth in 2020, this year looks set to be one of the best. Indeed, the bounce in activity is greater than many expected just a few months ago.

Global recovery: a bigger bounce

“It was the best of times; it was the worst of times”.1 is an apt summary of global economic developments this year and last.

This year, the World Bank forecasts the strongest postrecession recovery for the world economy in over eighty years.2 The Fed has revised its forecast of US GDP growth up to 7% (from 4.2% just seven months ago).3

Last year, the contraction of US real GDP was the largest recorded in the post-war period; for the eurozone, the drop was the biggest since its launch in 1999; and for the UK, 2020’s decline was the biggest since 1706, when the UK was at war with France.

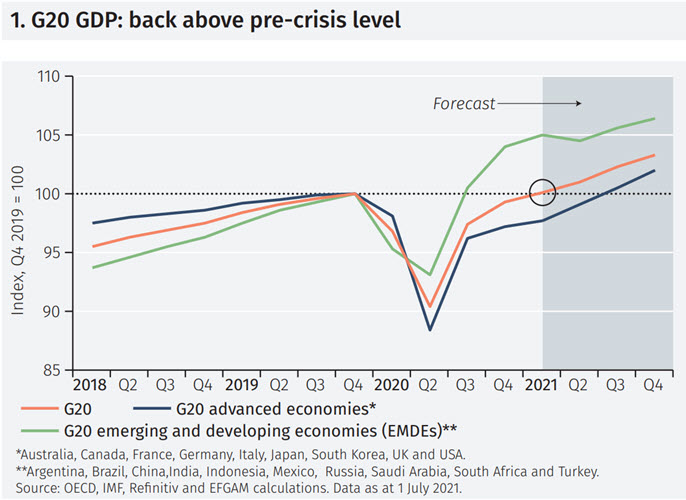

For the G20 economies in aggregate, real GDP was already above its pre-Covid level in the first quarter of 2021 (see Figure 1). That recovery was led by China; but South Korea and Australia were also above their pre-Covid levels. The US is set to pass a similar milestone in the second quarter; and most European economies will be close to their pre-pandemic GDP levels by late 2021/early 2022. Whereas the fiscal response to support the US economy was quick and substantial, the eurozone’s response, whilst still large, is more ‘slow burn’ – focusing on longer-term priorities such as curbing carbon emissions and the take-up of digital technologies.

Fast growth rates will not be sustained

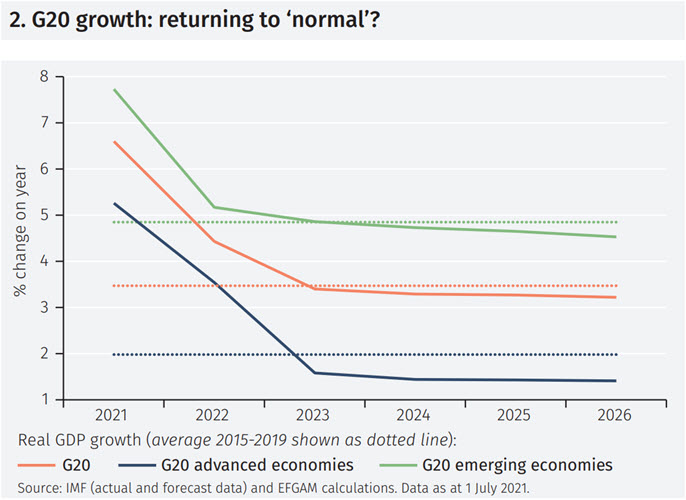

After pre-Covid activity levels are regained, what can we expect? Growth rates may remain elevated for a while as pent-up demand, especially for travel, holidays and entertainment, gradually recovers. But, looking ahead to 2023 and beyond, many (notably the IMF, whose forecasts are shown in Figure 2) are concerned that there will be a slowing to rates below those of the pre-Covid world. The concerns are on a number of fronts. Slower population and workforce growth are a feature of many advanced economies, as well as China. Weak productivity trends remain a concern and as Paul Krugman quipped, “productivity isn’t everything but, in the long run, it is almost everything”. That is, a country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker. The quality of the infrastructure needed to facilitate that – both of the ‘old school’ variety (transport, power, water and sanitation) and that of the digital world – varies enormously. Improving it is a priority everywhere.

Inflation pressures set to recede

The other major economic uncertainty for the months ahead relates to inflation. A rebound in inflation has been seen in many economies, notably the US. There are concerns that this may herald the start of a new, more inflationary period for the world economy; but most central banks, as well as many private sector forecasters, see this as temporary. For now, we are probably at a time of ‘peak inflation noise’: discerning the underlying trend is much more difficult than usual.

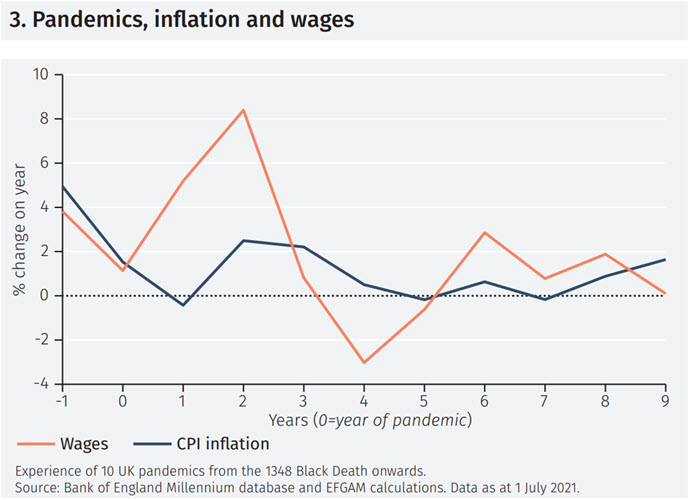

There are two main concerns relating to the consumer price inflation trend. The first is that it may be pushed up by higher wages. From bar staff in Britain to stevedores in San Francisco, labour shortages are seen around the world. A broad sweep of UK economic history shows that wages, driven higher by labour shortages, have typically risen sharply in the aftermath of pandemics (see Figure 3). However, the rise in wages tends to be temporary; and the general trend for several years after the pandemic is for lower, not higher, consumer price inflation. The reason, broadly, is that subdued demand tends to be a more important factor than supply shortages.

That suggests that the second inflationary force – supply shortages of semiconductors, new cars and building materials, etc. – may also not be long-lasting. Indeed, there are already signs of these shortages being corrected in the US, the advanced economy which has opened up the fastest. On balance, therefore, we tend to be sanguine about inflation prospects, a message which the US bond market also seems to have accepted.

The “three Cs”: climate change, cars and copper

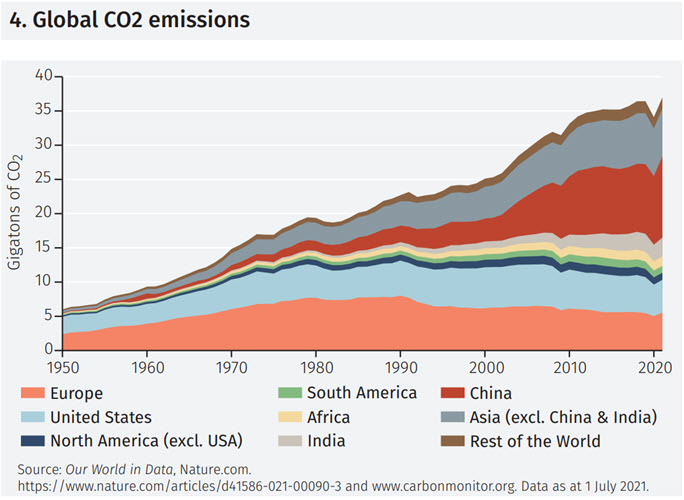

One welcome side-effect of the drop in activity in 2020 was the decline in carbon dioxide emissions. But that has not lasted. Data for the first four months of 2021 show a marked rebound (see Figure 4). A similar pattern was seen after the Global Financial Crisis: the reduction in carbon emissions at that time now appears as a temporary blip.

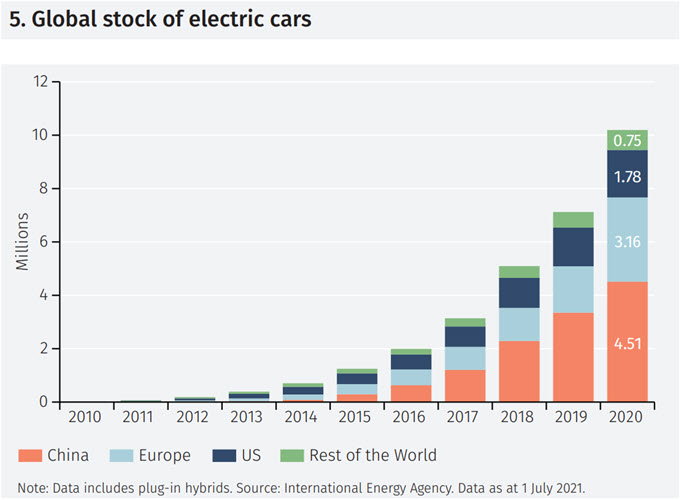

What is clear, however, is that there is a more determined focus on environmental issues and a greater co-ordinated international commitment to act. There has been a rapid growth in installed solar and wind power and plans for much more. Electric cars, a rarity just a few years ago, are now more common. But on all these fronts more needs to be done. Of the 1.4 billion cars on the road around the world, for example, only 10 million are electric vehicles (see Figure 5).

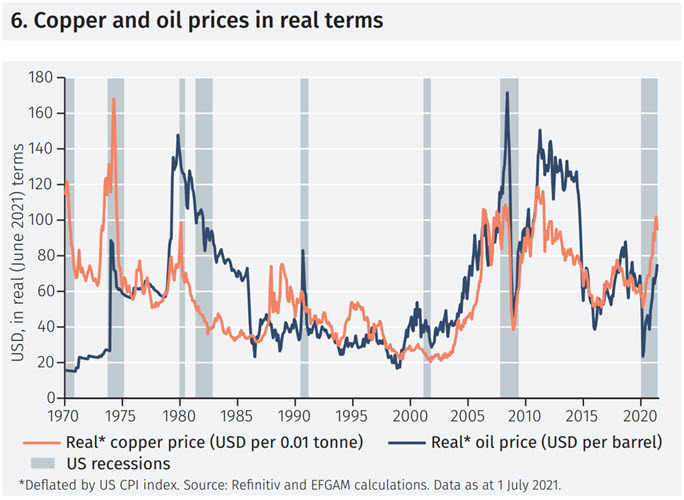

Electrification of the economy extends to many other areas. But that trend, in itself, will lead to greatly increased demand for some commodities (notably copper, aluminium, nickel and zinc). Although the copper price has risen sharply in recent months, in real terms it is still below previous peaks (see Figure 6). In that market, contrary to the general trend, strong demand may dominate a poor supply response.

Some are concerned that capital markets may struggle to finance the move to a new, greener infrastructure. To curb global warming to 2.0°C above pre-industrial levels, one estimate suggests US$50tr over the next 30 years will be needed.4 TheBut given that there has been a shift in the priorities of many investors to favour climate-focused investing, we doubt that there will be a problem in attracting the required finance. And some context is provided by the global fiscal response to the Covid pandemic: US$16 trillion so far.5 After paying that bill, the cost of mitigating climate change may seem much more acceptable.

To continue reading, please use the button below to download the full article.

Footnotes

1 The opening line of Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities.

2 World Bank Global Economic Prospects June 2021. https://tinyurl.com/yz35efjr

3 Fed Summary of Economic Projections. Measured as growth between the fourth quarter of the current year and the fourth quarter of the previous year.

4 Morgan Stanley estimates. See https://tinyurl.com/4yr48et5

5 IMF Fiscal Monitor April 2021.

Important Information

The value of investments and the income derived from them can fall as well as rise, and past performance is no indicator of future performance. Investment products may be subject to investment risks involving, but not limited to, possible loss of all or part of the principal invested.

This document does not constitute and shall not be construed as a prospectus, advertisement, public offering or placement of, nor a recommendation to buy, sell, hold or solicit, any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. It is not intended to be a final representation of the terms and conditions of any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. This document is for general information only and is not intended as investment advice or any other specific recommendation as to any particular course of action or inaction. The information in this document does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of the recipient. You should seek your own professional advice suitable to your particular circumstances prior to making any investment or if you are in doubt as to the information in this document.

Although information in this document has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no member of the EFG group represents or warrants its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Any opinions in this document are subject to change without notice. This document may contain personal opinions which do not necessarily reflect the position of any member of the EFG group. To the fullest extent permissible by law, no member of the EFG group shall be responsible for the consequences of any errors or omissions herein, or reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein, and each member of the EFG group expressly disclaims any liability, including (without limitation) liability for incidental or consequential damages, arising from the same or resulting from any action or inaction on the part of the recipient in reliance on this document.

The availability of this document in any jurisdiction or country may be contrary to local law or regulation and persons who come into possession of this document should inform themselves of and observe any restrictions. This document may not be reproduced, disclosed or distributed (in whole or in part) to any other person without prior written permission from an authorised member of the EFG group.

This document has been produced by EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited for use by the EFG group and the worldwide subsidiaries and affiliates within the EFG group. EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority, registered no. 7389746. Registered address: EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited, Leconfield House, Curzon Street, London W1J 5JB, United Kingdom, telephone +44 (0)20 7491 9111.