- Date:

- Author:

- Joaquin Thul

As the more severe effects of the pandemic start to recede and the world becomes used to living alongside Covid-19, the global economy is gradually returning to a more normal state. A survey conducted in April 2021 revealed that 75% of US adults expect the pandemic will drive long-term changes in their behaviour. These changes could relate to work, housing, transport habits or changes in consumption patterns and the way we socialize.1

During the early months of the pandemic consumers swiftly changed their spending patterns, shifting from leisure and recreation activities to spending more on durable goods for their homes. We observed a decline in gym memberships and a rise in purchases of home gym equipment. The revenue of Peloton, a company that sells exercise bikes and online workout classes, reached $1.8 billion in 2020, doubling that of the previous year and hitting 3.1 million global memberships during the year. Spending on cinema and concert tickets was replaced by a spike in subscriptions to on-demand streaming platforms, new televisions, and better home sound systems. In the UK, one in five homes signed up for a new video streaming subscription during the Covid-19 lockdown months. Additionally, as of the end of last year, almost 60% of UK households had at least one subscription to an on-demand video platform.2

These changes in consumer behaviour during the pandemic also contributed to an increase in global savings. According to data from Moody’s analytics, global savings increased by an extra $5.4 trillion since the start of the pandemic, representing 6% of global GDP. 3 This increase in savings was attributed to three main factors.

- Forced savings. The closure of non-essential shops across most developed economies during the peak of the pandemic together with restrictions to travel, forced consumers to reduce spending.

- Precautionary savings. Workers were concerned over the possibility of becoming unemployed or seeing a reduction in work hours, creating an incentive to increase savings as a safety net. The uncertainty over the length and stringency of lockdown measures favoured a more cautious approach to spending.

- Fiscal support. As part of the policy support during the pandemic governments implemented measures such as job retention schemes, extended unemployment benefits, stimulus cheques and direct transfers. In lower-income households, these compensated for some of the loss of income as a result of a reduction in working hours. However, in higher-income groups, these transfers increased household savings.

Consumption patterns have already started to change again, shifting away from durable goods towards leisure and recreation activities as consumers get used to socializing again. Therefore, the excess savings accumulated during the pandemic are expected to drive a spending spree in services, particularly in developed economies.

A high vaccination rate against Covid-19 will be key to supporting the lifting of restrictions to mobility and, alongside the recovery in the labour market, this should improve consumer confidence. These, together with high levels of excess savings, will boost demand and consumer spending as countries reopen.

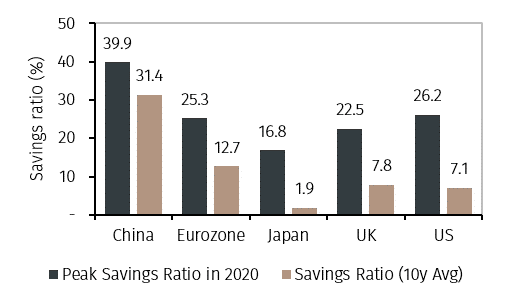

In countries such as the US, UK and Japan, the savings ratio increased to double-digit figures during 2020, representing more than double the average of the last ten years. In China, which already had a high savings ratio, savings increased by a lower magnitude during the pandemic showing a smaller change in consumer patterns (Figure 1).

Source: Refinitiv, Barclays and EFGAM

However, accumulated savings have not been distributed evenly across income groups. Higher earning households saved more than lower earning ones. Therefore, the lower marginal propensity to consume from wealthier households could reduce the effect on growth in some economies.

Spending spree

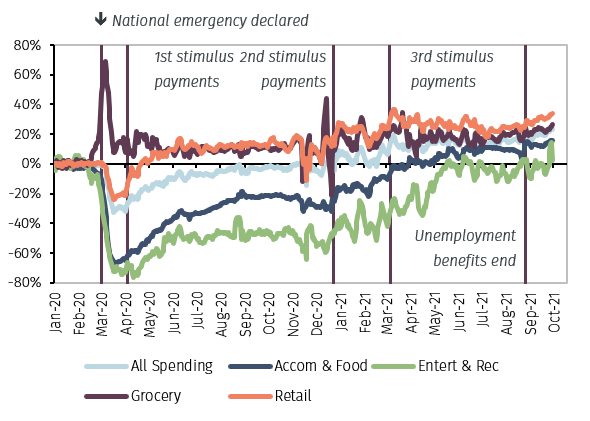

Moody’s estimates one-third of global excess savings will be spent in 2021, adding over 2% to global GDP this year and an additional 2% in 2022. As of the end of October 2021, retail spending by US consumers increased by 23% compared to January 2020. This was facilitated by the three rounds of stimulus payments by the US government, which contributed to bring spending above pre-pandemic levels (Figure 2).4 Although spending in sectors such as groceries and retail has increased by 34% and 26% respectively, other sectors have still to catch up. The slow return of consumers to outdoor activities means that although spending in restaurants and hotels and entertainment and recreation picked-up by 16% and 2.5% respectively in comparison to January 2020, these figures are still low relative to the rest of the economy.

Source: Affinity and EFGAM

In the UK, the Bank of England estimates consumers accumulated more than £200 billion in savings since the start of the pandemic. The central bank expects household consumption will increase by 5.25% in 2021 and 9.25% in 2022. Although consumption has picked-up this year, households remain cautious across lower income groups. Therefore, the BoE expects the full effect of the deployment of excess savings to be observed in 2022, when the savings rate is projected to return to its 10-year average of around 7%.

Differences among consumers

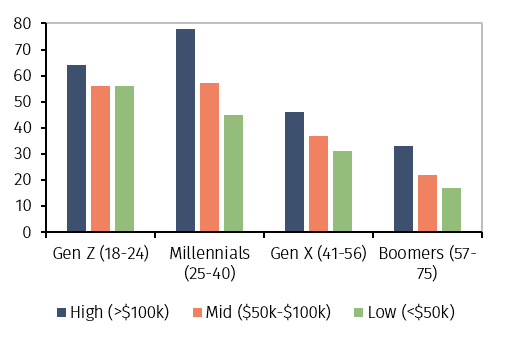

A survey conducted by McKinsey & Company revealed younger cohorts of consumers across most income groups in the US are expected to increase leisure spending by over 50% in 2021 and 2022 (Figure 3). The asymmetric distribution of savings across income groups will affect the speed at which these groups increase consumption. Older and wealthier households in developed economies have fared the effects of the pandemic better than younger households. However, the latter have a higher marginal propensity to consume and therefore will be more likely to boost spending on holidays and events such as concerts, festivals and sports, and overall social activities such as dinning and recreation.

Source: McKinsey & Company

The marginal propensity to consume is determined by the composition of savings during the last year and a half. Different to previous crises when consumers worried over the health of the financial system, during the Covid-19 crisis households increased their savings in financial assets, particularly in the form of liquid deposits. As an example, in Q1-2021 financial investments by households in the euro area increased at an annual rate of 4.8%. While investments in shares and other equity investments picked-up by 3.8%, currency and deposits grew at a rate of 8.2% in the quarter. The fact that a high proportion of savings have been held in relatively liquid bank deposits over the last year, despite low interest rates, reinforces the argument that the marginal propensity to consume will be higher than in previous crises, when savings went into real assets (i.e. real estate).

Conclusion

Changes to consumer behaviour as a result of the pandemic has already become evident in developed economies. As vaccination rates increase and confidence returns, consumers have started to shift away from spending on durable goods back towards travel, leisure and entertainment sectors. As a result, spending on holidays, theme parks, cinemas, concerts, healthcare and fitness, which were off the menu last year, will return in 2022 providing attractive investment opportunities.

The differences among consumers’ age and income level will determine the sectors and industries which will capture most of the spending capacity. Therefore, it remains key to understand these changing trends and invest in industry leaders and disrupting companies across multiple regions that will capture most of the marginal propensity to consume of the different income groups.

This will create opportunities for airlines, hotels, booking platforms, entertainment companies, healthcare, and fitness firms to benefit from this rising trend. The effects of rising price pressures and higher inflation could reduce real disposable incomes and raise fears of an earlier-than-expected increase in interest rates. However, this will also reduce the attractiveness of keeping large savings in liquid deposits and increase even more the incentives to spend. We maintain our expectation that developed markets central banks will look through these inflationary pressures, maintaining monetary accommodation which will favour the economic recovery and support the rise in consumer spending.

Footnotes

1 “How to make sense of consumer behaviour after the pandemic”. Forrester, 2021.

2 Entertainment On-Demand Service. Kantar, 2020.

3 “Hot Start for High-Yield”. Moody’s Analytics, 2021.

4 Affinity Solutions, via tracktherecovery.org

Important Information

The value of investments and the income derived from them can fall as well as rise, and past performance is no indicator of future performance. Investment products may be subject to investment risks involving, but not limited to, possible loss of all or part of the principal invested.

This document does not constitute and shall not be construed as a prospectus, advertisement, public offering or placement of, nor a recommendation to buy, sell, hold or solicit, any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. It is not intended to be a final representation of the terms and conditions of any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. This document is for general information only and is not intended as investment advice or any other specific recommendation as to any particular course of action or inaction. The information in this document does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of the recipient. You should seek your own professional advice suitable to your particular circumstances prior to making any investment or if you are in doubt as to the information in this document.

Although information in this document has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no member of the EFG group represents or warrants its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Any opinions in this document are subject to change without notice. This document may contain personal opinions which do not necessarily reflect the position of any member of the EFG group. To the fullest extent permissible by law, no member of the EFG group shall be responsible for the consequences of any errors or omissions herein, or reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein, and each member of the EFG group expressly disclaims any liability, including (without limitation) liability for incidental or consequential damages, arising from the same or resulting from any action or inaction on the part of the recipient in reliance on this document.

The availability of this document in any jurisdiction or country may be contrary to local law or regulation and persons who come into possession of this document should inform themselves of and observe any restrictions. This document may not be reproduced, disclosed or distributed (in whole or in part) to any other person without prior written permission from an authorised member of the EFG group.

This document has been produced by EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited for use by the EFG group and the worldwide subsidiaries and affiliates within the EFG group. EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority, registered no. 7389746. Registered address: EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited, Leconfield House, Curzon Street, London W1J 5JB, United Kingdom, telephone +44 (0)20 7491 9111.