- Date:

The objective of the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy is to achieve the dual goals of maximum employment and price stability. While many central banks have a main objective for price stability and often a secondary goal of smoothing the business cycle, the Federal Reserve Act is unusual in that it provides an explicit goal for maximum employment that, furthermore, is of equal importance to its goal for price stability.1

Quantifying the Fed’s inflation and unemployment objectives

Interestingly, these goals can be given a numerical definitioneven though no such definition is provided in the legislation. Every quarter, the members of the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (FOMC) provide their views of several macroeconomic variables for the next few years and in the “longer run.” When the “longer run” is reached is not clear, but one can think of it as when the economy has fully recovered from whatever cyclical situation it is currently experiencing.

Since the Fed can influence inflation, the longer run forecasts indicate what inflation rate FOMC members are aiming for. That longer run rate, which is 2%, is often interpreted as the Fed’s inflation target.

Furthermore, FOMC members also indicate what they think the unemployment rate will be in the longer run. Since experience suggests that monetary policy has no long run effects on real economic variables such as economic growth or employment, the unemployment rate in the longer run can be interpreted as the lowest unemployment rate – which corresponds to the maximum employment rate – that the Fed believes it can achieve and maintain. This is 4%.

The Fed’s loss function

In sum, how well the Federal Reserve is achieving its goals can be assessed by looking at the deviation of inflation from 2% and the deviation of unemployment from 4%. Since deviations can be positive or negative and it is often felt that both are equally undesirable, economists often define the loss as equal to the sum of the squared deviation of inflation from target and unemployment from its longer run level:

Loss = (inflation – 2%)2 + (unemployment rate – 4%)2

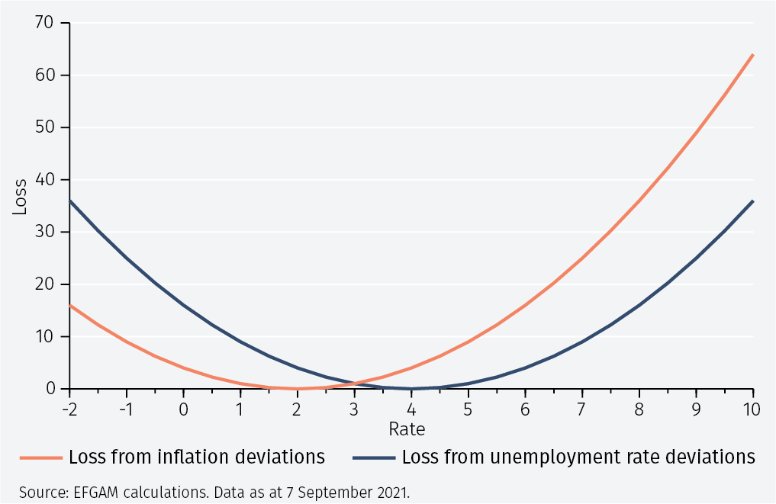

This loss function is illustrated in Figure 1.

Four aspects of this loss function deserve comment.

First, while it only involves two variables, in practice the Fed is concerned by many more measures of inflation and unemployment. Thus, the loss function and the associated analysis should be seen as a short cut to understanding Fed policy making.

Second, the losses are minimised when inflation and the unemployment rate are at the targeted levels.

Third, the costs of deviating from target rise as the deviations of inflation and unemployment grow larger. That is important for thinking about FOMC members’ views about monetary policy in the recent past.

Fourth, too low rates of inflation and unemployment are as costly as too high rates: that is, the loss function is symmetric. While the notion of symmetric losses from inflation deviations is mainstream, the idea that central banks care as much about unemployment being below the long run level as they do about unemployment being above it is debatable.

Indeed, in recent cycles the US unemployment rate has fallen below the level that was previously thought to be consistent with full employment yet that, by itself, did not elicit a policy response: rather the Fed concluded that the NAIRU (non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment) had declined. And in announcing last year the Fed’s new policy strategy which emphasises the benefits of a strong labour market, Chairman Powell said that “our revised statement says that our policy decision will be informed by our ‘assessments of the shortfalls of employment from its maximum level’ rather than by ‘deviations from its maximum level’ as in our previous statement.”2 While this signalled that a symmetric loss arising from deviations of unemployment from its longer-term level is no longer appropriate for the Fed, the unemployment rate has so rarely been below its long-run level that in practice this distinction may be moot.

Recent US macroeconomic history

Figure 2 shows PCE inflation and the unemployment rate since January 2010. While inflation was close to the 2% target during most of the period, the unemployment rate started the period far above the 4% objective but gradually declined to it, and even fell temporarily below it before Covid-19 struck.

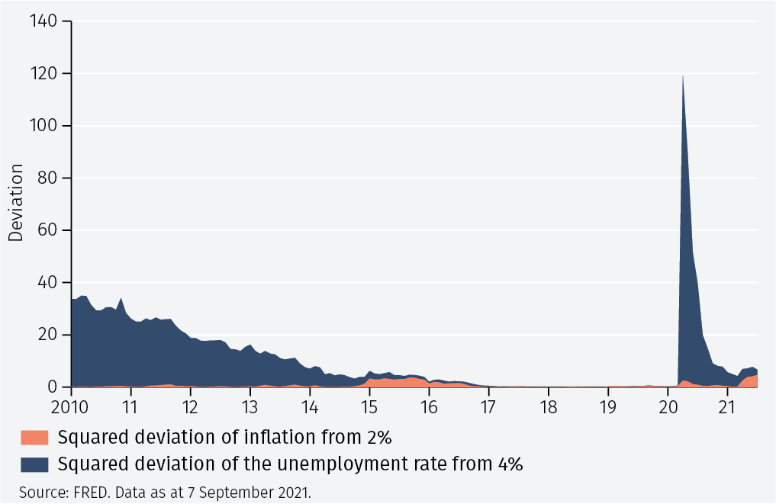

Figure 3 shows the squared deviations of inflation from 2% and the unemployment rate from 4%, individually, and their sum. The figure shows how well the Fed is achieving its objectives. Importantly, the figure indicates to what extent the losses stem from inflation or the unemployment rate deviating from target.

The figure illustrates two important points. First, deviations of unemployment from target have been much more important as a source of losses than deviations of inflation from target. That helps explain why the Federal Reserve since the onset of the Covid pandemic appears to have been more preoccupied by the high unemployment rate than the high inflation rate.

Second, following the rapid rise in inflation since May, inflation deviations are now more important than unemployment deviations, suggesting that the FOMC’s focus could shift. However, since the Fed believes that the rise in inflation is temporary, it seems likely to continue to concentrate on the high unemployment rate.

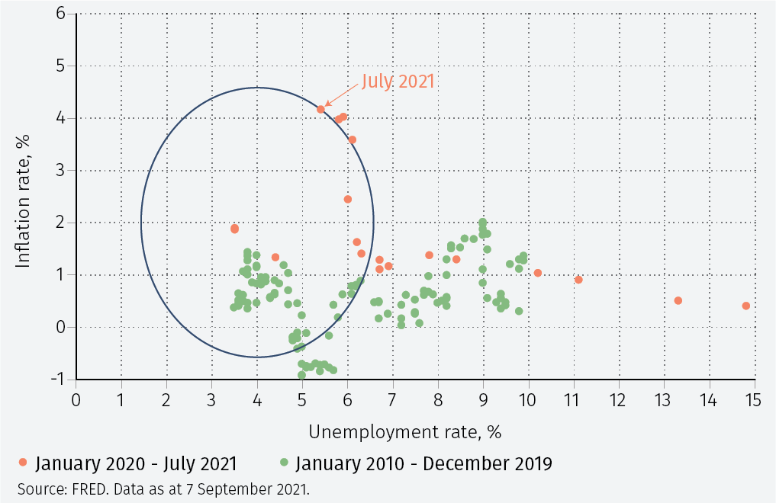

Another way to view the Fed’s loss function is presented in Figure 4, which shows inflation and the unemployment rate, together with a circle centred at a point given by inflation and unemployment equal to target, which sometimes is referred to as the Fed’s “bliss point.” The circle is drawn to pass through the July 2021 data point, with inflation of 4.2% and an unemployment rate of 5.3%. The radius of the circle measures the value of the loss function.3

The figure indicates again that while fluctuations in unemployment have been a greater source of movements of the economy away from the Fed’s bliss point than inflation, in the last few months it is the sharp rise in inflation that is the main explanation for the worsening macroeconomic outcomes as experienced by the Fed.

Conclusions

How well the Fed has achieved its objectives can be assessed using a formal loss-functional analysis. Such an investigation shows that deviations of unemployment from its long-run level, which can be thought of as the Fed’s target, have been much more important as a source of concern than deviations of inflation from the 2% target.

In turn, that observation helps in explaining why the Fed has not been quick to announce tapering of bond purchases at the current juncture, in which unemployment is only gradually declining towards target but inflation has surged.

1 See Section 2.A of the Federal Reserve Act www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/section2a.htm

2 See https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/powell20200827a.htm

3 To be precise, it measures the square root of the loss. Amusingly, the radius of the circle is obtained by applying Pythagoras’ theorem to the loss function, indicating that high school mathematics is not a waste of time.

Important Information

The value of investments and the income derived from them can fall as well as rise, and past performance is no indicator of future performance. Investment products may be subject to investment risks involving, but not limited to, possible loss of all or part of the principal invested.

This document does not constitute and shall not be construed as a prospectus, advertisement, public offering or placement of, nor a recommendation to buy, sell, hold or solicit, any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. It is not intended to be a final representation of the terms and conditions of any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. This document is for general information only and is not intended as investment advice or any other specific recommendation as to any particular course of action or inaction. The information in this document does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of the recipient. You should seek your own professional advice suitable to your particular circumstances prior to making any investment or if you are in doubt as to the information in this document.

Although information in this document has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no member of the EFG group represents or warrants its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Any opinions in this document are subject to change without notice. This document may contain personal opinions which do not necessarily reflect the position of any member of the EFG group. To the fullest extent permissible by law, no member of the EFG group shall be responsible for the consequences of any errors or omissions herein, or reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein, and each member of the EFG group expressly disclaims any liability, including (without limitation) liability for incidental or consequential damages, arising from the same or resulting from any action or inaction on the part of the recipient in reliance on this document.

The availability of this document in any jurisdiction or country may be contrary to local law or regulation and persons who come into possession of this document should inform themselves of and observe any restrictions. This document may not be reproduced, disclosed or distributed (in whole or in part) to any other person without prior written permission from an authorised member of the EFG group.

This document has been produced by EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited for use by the EFG group and the worldwide subsidiaries and affiliates within the EFG group. EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority, registered no. 7389746. Registered address: EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited, Leconfield House, Curzon Street, London W1J 5JB, United Kingdom, telephone +44 (0)20 7491 9111.