- Date:

The severity of the Covid-19 pandemic has varied sharply between countries. In this issue of Infocus, Stefan Gerlach and Joaquin Thul ask what factors may explain these differences. They find that as much as about half of the variation between countries in Covid-19 mortality is explained by four variables: the median age of the population, tourist arrivals, inequality and a measure of government effectiveness.

Covid-19 has had huge social and economic consequences. With the virus often causing serious illness and sometimes death, governments have shut down economies to stop its spread. The risk of falling ill has also led the public to voluntarily refrain from shopping, going to bars and restaurants and from travelling. The overall impact was responsible for deep recessions across the world.

The severity of the Covid-19 pandemic, as captured by deaths per million inhabitants, has varied sharply between countries. In early 2020, Italy and Spain appeared to experience particularly severe pandemics. During the spring of 2020 Sweden also seemed to suffer an unusually serious pandemic. Other countries, including New Zealand, Australia, and Finland, appeared to have been more fortunate.

What factors may explain these differences in mortality? Do they imply that some countries managed the pandemic better than others? Or do they simply reflect the fact that countries differ in important respects. Most obviously, since Covid-19 was generally a more severe disease among older patients, do differences in the average or median age of the population help explain differences in mortality?

Structural determinants of mortality

To address this and other questions, a data set comprising 135 countries is studied. As shown in Table 1, a range of different variables are included. These are divided into three areas:

- Susceptibility to the virus:

Reflected by the median age of the population. Mortality is likely to be higher in countries with an older population. - Risk of contagion:

Captured by population density and a measure of the extent to which a country may be disproportionally at risk from contagion. The rationale is that higher population density may be associated with more contagion and therefore higher mortality. High income countries are more densely populated, with over 80% of their populations living in urban areas. In low-income economies this proportion drops to just one third of the population. Additionally, countries whose populations travel more or who receive many travellers from abroad may be more at risk of contagion. This is measured here by the ratio of international arrivals to the size of the population. - Policy and Governance:

Domestic policy choices and the ability of governments to manage a crisis may also have played a role in the pandemic. These factors may be encompassed in variables that capture income inequality, a series of governance metrics, the stringency of lockdowns and the level of GDP.

- Income inequality. Countries with a more egalitarian income distribution may do more to protect lower income earners that often are unable to work from home, for instance by offering a better safety net.

- Ability of the government to manage a crisis. This is difficult to measure but may be correlated with indices on government effectiveness, the rule of law, the control of corruption, the degree of political stability or the quality of regulation. Countries with more capable governments are likely to be better positioned to mitigate pandemics.

- Voice and accountability. Governments that are subject to public scrutiny have a strong incentive to enact policies to protect the wellbeing of the population.

- Stringency of lockdowns. A policy choice of greater stringency is expected to reduce mortality, leading to a negative relationship between the two variables. But countries that experienced more severe pandemics are likely to have adopted tighter lockdowns, leading to a positive relationship between them. This implies that there are two relationships: one from stringency to mortality, and one from mortality to stringency.

- Level of GDP. While income on its own is unlikely to be correlated with mortality, it may be correlated with other important variables that are omitted from the study. For instance, higher-income countries may have better health systems, leading to negative relationship between GDP and mortality.

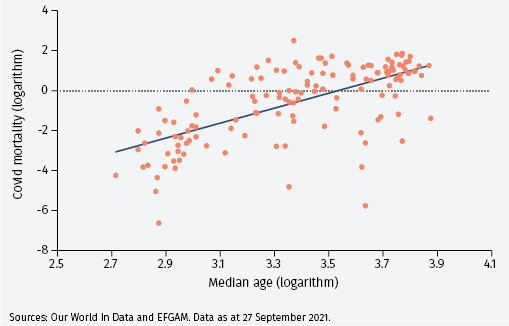

As a preliminary, Figure 1 presents a scatter plot of the number of deaths per million inhabitants over the period April 2020 to August 2021 against the median age of the population and shows that there is a positive relationship between these variables (correlation = 0.64). However, there is substantial variation between countries, with some with relatively old populations reporting low mortality. That finding suggests that the median age is not the only variable explaining the severity of the pandemic but that other factors will have been important too.

To continue reading, please use the button below to download the full article.

Important Information

The value of investments and the income derived from them can fall as well as rise, and past performance is no indicator of future performance. Investment products may be subject to investment risks involving, but not limited to, possible loss of all or part of the principal invested.

This document does not constitute and shall not be construed as a prospectus, advertisement, public offering or placement of, nor a recommendation to buy, sell, hold or solicit, any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. It is not intended to be a final representation of the terms and conditions of any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. This document is for general information only and is not intended as investment advice or any other specific recommendation as to any particular course of action or inaction. The information in this document does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of the recipient. You should seek your own professional advice suitable to your particular circumstances prior to making any investment or if you are in doubt as to the information in this document.

Although information in this document has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no member of the EFG group represents or warrants its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Any opinions in this document are subject to change without notice. This document may contain personal opinions which do not necessarily reflect the position of any member of the EFG group. To the fullest extent permissible by law, no member of the EFG group shall be responsible for the consequences of any errors or omissions herein, or reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein, and each member of the EFG group expressly disclaims any liability, including (without limitation) liability for incidental or consequential damages, arising from the same or resulting from any action or inaction on the part of the recipient in reliance on this document.

The availability of this document in any jurisdiction or country may be contrary to local law or regulation and persons who come into possession of this document should inform themselves of and observe any restrictions. This document may not be reproduced, disclosed or distributed (in whole or in part) to any other person without prior written permission from an authorised member of the EFG group.

This document has been produced by EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited for use by the EFG group and the worldwide subsidiaries and affiliates within the EFG group. EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority, registered no. 7389746. Registered address: EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited, Leconfield House, Curzon Street, London W1J 5JB, United Kingdom, telephone +44 (0)20 7491 9111.