- Date:

Infocus - The Federal Minimum Wage in the US

With President Biden proposing an increase in the Federal Minimum Wage from $7.25 to $15 per hour, market participants are naturally worried about whether such a change could reduce US firms’ profitability and raise unemployment, slowing the broader economy. In this issue of Infocus, Stefan Gerlach and GianLuigi Mandruzzato look at this question in more detail.

President Biden has proposed that the Federal Minimum Wage (FMW) be increased to $15 per hour. Given that it currently is $7.25, market participants are concerned that such a large increase would constitute a cost-push shock that would reduce the earnings of US firms and raise unemployment, slowing the broader economy, and that wage inflation would seep into general price inflation.

To assess that question, it should be recalled that US state laws also prescribe minimum wages, generally at a higher level than Federal law. Furthermore, most workers earning hourly wages earn above the minimum wage. The impact on actual wages earned of an increase in the FMW will therefore be largely dampened.

State minimum wage laws

To see how much actual wages may change, it is useful to start by considering state minimum wage legislation. The US minimum wage is regulated by the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). The Act states that employees of businesses either with annual sales of at least $500,000 or that participate in interstate commerce, and workers in the public sector must be paid the FMW.1 The law allows states to set their own minimum wages. However, if they do so, workers covered by the FLSA must receive the highest of the two rates.

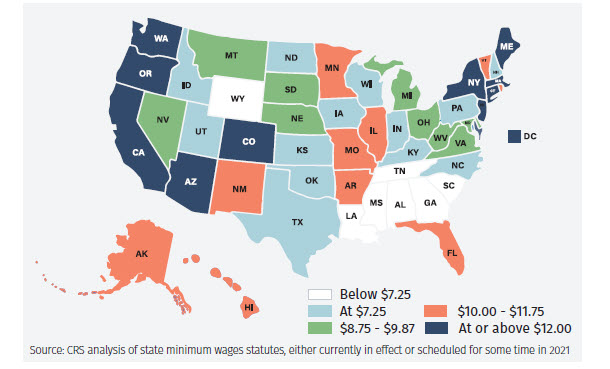

The FMW was last raised to $7.25 per hour in 2009. However, as at the beginning of 2021, 30 states and the District of Columbia apply minimum wages above the FMW, ranging from $1.50 to $7.75 above the latter.2 Another 13 states have minimum wages equal to the FMW, five have no minimum wage requirement and two have a minimum wage lower than the FMW. As a result of rising state minimum wages, the share of the U.S. civilian labour force for which the FMW is the floor fell to about 40% from 80% at the beginning of the century.

According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), 1.6 million workers earned wages at or below the FMW in 2019. These represent only about 1% of all US civilian employment. The BLS notes that minimum wage workers tend to be young: 40% of minimum wage earners are aged 25 or less. Also, women and workers without a high school diploma are three times more likely to earn the FMW than men and college graduates.

Of the workers earning wages at or below the FMW, 75% were employed in services, the vast majority in restaurants and other food services. Many of them are tipped workers, for whom the FLSA establishes the minimum wage at $2.13 per hour but adds that it must be increased to match the applicable minimum wage rate if earned tips do not fill the gap.3

Using shares of the civilian labour force across states to calculate the effective FMW results in an estimate of approximately $9.70 per hour, or 34% above the FMW. The effective FMW is set to rise further. Several of the states with minimum wages above the FMW have already scheduled further increases, with nine states and the District of Columbia planning to raise their minimum wage to $15 per hour by 2026 at the latest.4 Furthermore, 10 states and the District of Columbia have indexed their minimum wage rate to a measure of inflation and eight more states are scheduled to do the same by 2027.

The distribution of wages

The fact that the labour-force weighted state minimum wage is above the current FMW implies that an increase in the FMW to $15 would thus raise the effective minimum wage by 55%, much less than the 107% increase from $7.25 to $15.

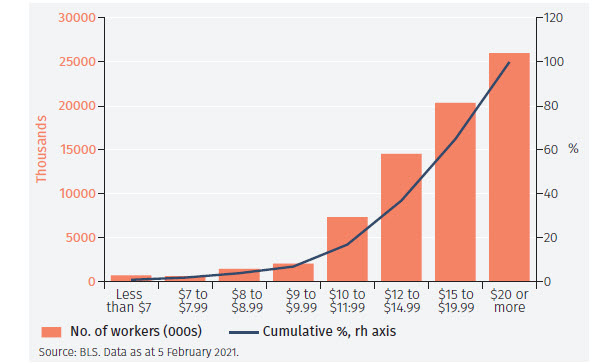

A second consideration that will dampen the impact of the increase in the FMW is the fact that most workers earn more than that per hour. Figure 2 shows the hourly wage rate for workers paid by the hour, of which there were 73.3 million in 2020. Of these, 14.6 million or 37% earned less than $15 per hour.

The weighted average hourly wage for workers earning less than $15 is $11.50, that is, substantially above the labour-force weighted state minimum wage rate of $9.70. This implies that the direct effect of the proposed increase in the FMW would be to push up by 30% the wages of affected workers, who represent about 10% of US total civilian employment Of course, the indirect effect would be larger, as workers currently earning just above $15 an hour would surely push for wage increases too.

The effects on unemployment

The consensus view of the economic effects of increases in minimum wages has shifted over time. The conventional view used to be that increases in minimum wages would have harmful macroeconomic effects, increasing unemployment for low-wage workers.

In response to research findings in the 1980s that failed to detect evidence of such effects, it became broadly accepted that increases in minimum wages have much less harmful consequences than previously believed, if any.

One argument is that low-wage employers may have wagesetting power (in the sense of being monopoly buyers of labour), which allows them to push wages below the free competition wage rate. In this case, a minimum wage will increase employment because it attracts into the labour force previously disincentivised workers.

However, it is easy to see that estimates of the impact of minimum wages could be seriously biased. For instance, if minimum wages are raised during an economic expansion, the unemployment consequences may be underestimated. Furthermore, studies that focus on the employment consequences of minimum wage increases may fail to detect if firms cease hiring low-skilled workers and instead hire more productive higher-skilled workers.

A recent survey of the large research literature on the effects of increases in minimum wages concludes that the majority of studies found a statistically significant negative effect on employment.5 This effect was stronger for teens and young adults, and less educated workers, who are most likely to be negatively affected by an increase.

Along these lines, the bipartisan US Congressional Budget Office recently concluded that the proposed minimum wage increase to $15 per hour would reduce overall employment by 1.4 million jobs. However, the CBO also noted that a higher minimum wage would lift 0.9 million people out of poverty, acknowledging a strong argument in favour of raising the FMW to make the recovery more inclusive and thereby reducing inequality in the US society.

Conclusions

The proposed increase in the FMW from $7.25 to $15 per hour would lead to an increase in affected workers’ wages of about 30%. This is likely to reduce employment of young and less educated workers. However, the impact on overall employment is likely to be small since the US economy is predicted to grow strongly in 2021-22.

Footnotes

1 The exceptions are young workers, some students, and disabled workers.

2 Some local government entities and private companies have higher minimum wage rates than the federal or state minimum. In addition, in some states a separate minimum wage applies to small employers as well as other exceptions to the local standard rate.

3 According to the US Department of Labor, “tipped workers” are those who “customarily and regularly receive more than $30 per month in tips.”

4 The nine states are: California, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Virginia. These states together with the District of Columbia account for about 40% of the total civilian labour force.

5 See ‘Myth or measurement: what does the new minimum wage research say about minimum wages and job loss in the United States?’, David Neumark and Peter Shirley, NBER Working Paper 28388, January 2021.

Important Information

The value of investments and the income derived from them can fall as well as rise, and past performance is no indicator of future performance. Investment products may be subject to investment risks involving, but not limited to, possible loss of all or part of the principal invested.

This document does not constitute and shall not be construed as a prospectus, advertisement, public offering or placement of, nor a recommendation to buy, sell, hold or solicit, any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. It is not intended to be a final representation of the terms and conditions of any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. This document is for general information only and is not intended as investment advice or any other specific recommendation as to any particular course of action or inaction. The information in this document does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of the recipient. You should seek your own professional advice suitable to your particular circumstances prior to making any investment or if you are in doubt as to the information in this document.

Although information in this document has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no member of the EFG group represents or warrants its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Any opinions in this document are subject to change without notice. This document may contain personal opinions which do not necessarily reflect the position of any member of the EFG group. To the fullest extent permissible by law, no member of the EFG group shall be responsible for the consequences of any errors or omissions herein, or reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein, and each member of the EFG group expressly disclaims any liability, including (without limitation) liability for incidental or consequential damages, arising from the same or resulting from any action or inaction on the part of the recipient in reliance on this document.

The availability of this document in any jurisdiction or country may be contrary to local law or regulation and persons who come into possession of this document should inform themselves of and observe any restrictions. This document may not be reproduced, disclosed or distributed (in whole or in part) to any other person without prior written permission from an authorised member of the EFG group.

This document has been produced by EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited for use by the EFG group and the worldwide subsidiaries and affiliates within the EFG group. EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority, registered no. 7389746. Registered address: EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited, Leconfield House, Curzon Street, London W1J 5JB, United Kingdom, telephone +44 (0)20 7491 9111.