- Date:

Infocus - With energy prices and inflation at a decade high and economic growth moderating, many commentators fear the return of stagflation.

With energy prices and inflation at a decade high and economic growth moderating, many commentators fear the return of stagflation. In this edition of Infocus, GianLuigi Mandruzzato looks at the differences in the institutional and economic framework to 50 years ago.

Surging commodity prices, including energy, and moderating economic growth have led many commentators to warn about the risks of stagflation, a situation where the economy grows below its potential and inflation is persistently high or rising.1 However, comparing today’s economic and institutional framework to the 1970s, the return of stagflation seems remote.2

Growth is above potential

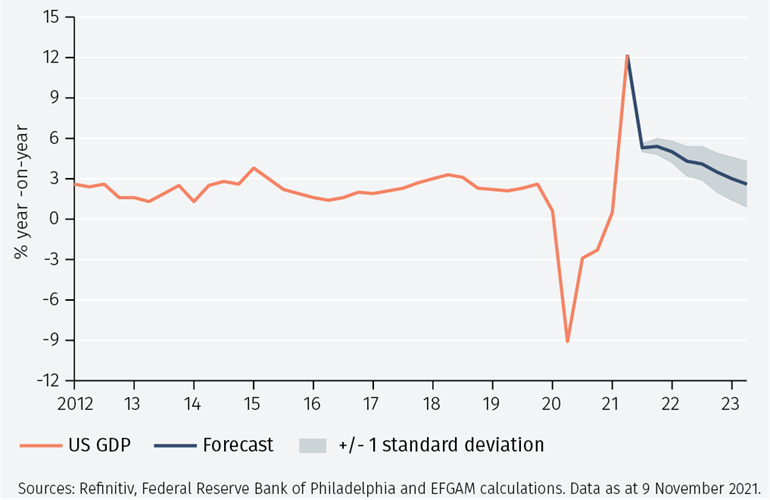

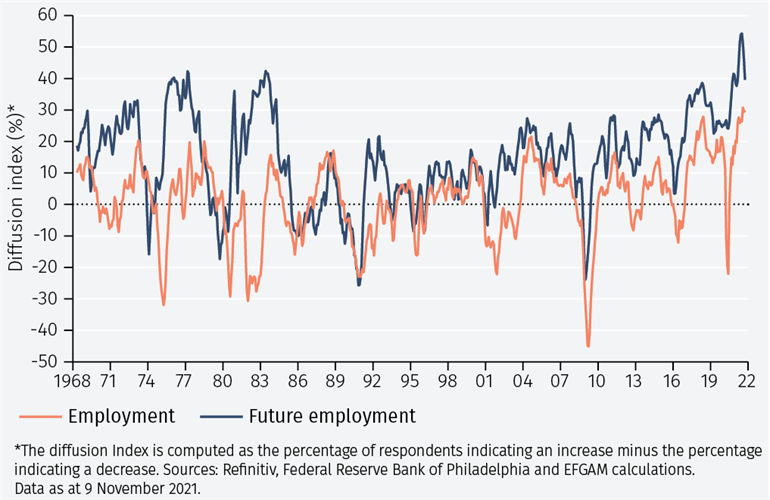

First, there is no stagnation. Despite issues linked to bottlenecks in global supply chains, the global economy is not weak. Thanks to a supportive policy mix, growth is expected to remain above potential in 2022 in most economies, including the US where the Congressional Budget Office estimates potential GDP growth of around 2% (see Figure 1a). These projections are underpinned by abundant private sector savings and pent-up demand for leisure and durable goods amid high demand for workers (see Figure 1b).

The risk of an inflation spiral is low

Turning to inflation, many commentators fear that rampant price and wage increases will force central banks to tighten policy at the risk of pushing the economy into recession. However, differences in the institutional framework compared to the 1970s suggest that the current commodity price shock is unlikely to get entrenched in the price formation process.

Today, most central banks in developed countries are independent and pursue an explicit inflation target of about 2%.3 By contrast, in the 1970s monetary policy was set by governments in most European countries and even the Federal Reserve accommodated the government’s focus on growth over controlling inflation. Today’s institutional framework should anchor inflation expectations, reducing the risk that the current price shock will lead to second-round effects on wages.

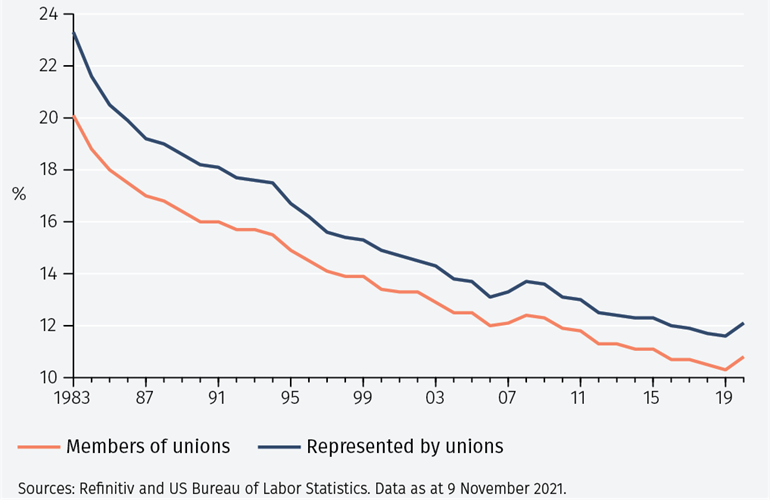

The risk of a wage-price spiral is also limited because workers’ bargaining power is hampered by a gradual decline in unionisation rates (see Figure 2). Data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, available since 1983, show the share of workers that are either members of or are represented by unions has halved in the last 40 years. Academic research shows that peak unionisation was reached in the 1950s at about 35% and has been in decline since then.4 Furthermore, automatic wage indexation to inflation is now virtually absent while it covered about 60% of US unionised workers in the 1970s.5

Additionally, the increased degree of globalisation and competition in goods and services markets, together with low and stable inflation, limits the pass-through of commodity price shocks to consumer prices. Despite stalling since the onset of the Global Financial Crisis, the ratio of global trade to GDP is twice that in the early 1970s (see Figure 3). Competitive pricing also stems from the establishment of strict antitrust policies in most countries and the widespread use of online shopping which facilitates easy price comparison.

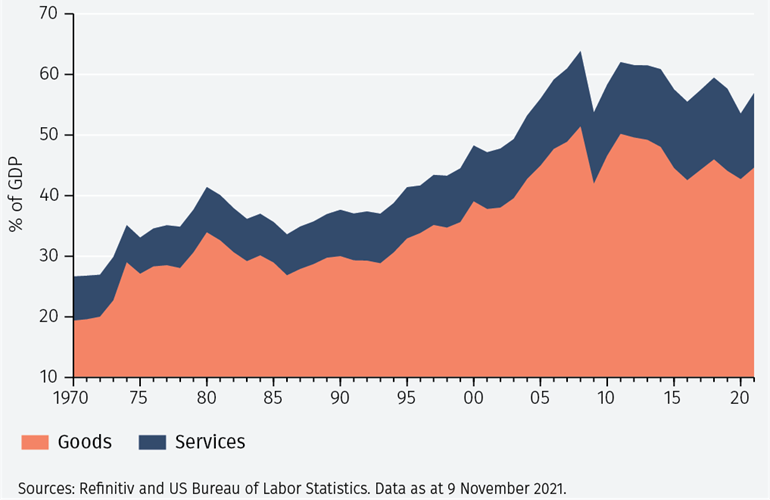

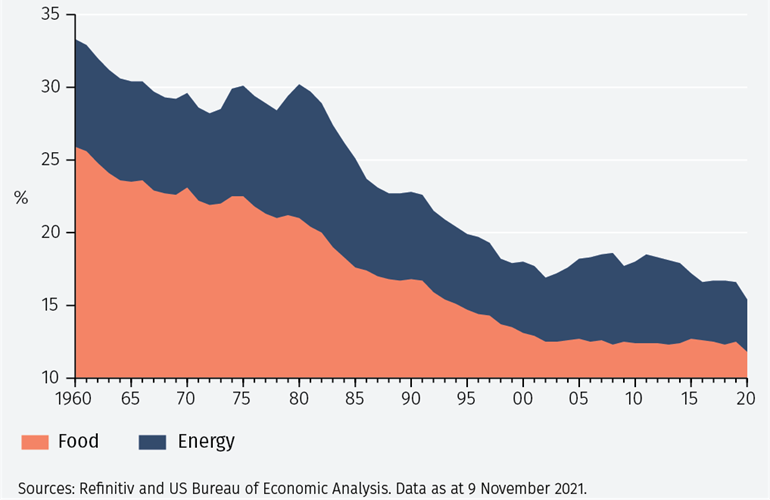

It is also important to note that structural changes in households’ consumption habits limits the impact of commodity price shocks to overall inflation. Over the last 50 years, the combined share of energy and food in US total personal consumption expenditure (PCE) has fallen from about 29% to about 15% (see Figure 4). This mechanically reduces the direct impact on the inflation rate of a commodity price shock compared to the 1970s. Furthermore, the production of goods has also become more energy efficient, limiting the effect of energy prices on production costs.

Finally, the nature of the energy price shock is different to those of the 1970s. The first oil crisis followed the OPEC embargo between October 1973 and March 1974: OPEC halted exports to oil-dependent Western countries as retaliation for supporting Israel in the Yom Kippur War. The second oil crisis followed the sharp drop in OPEC oil production after the Iranian Revolution in 1979 and the start of the Iran-Iraq war in 1980. The shortage of energy inputs pushed inflation higher and restrained production, exacerbating the negative effects on the economy. These increases were thus caused by political rather than economic factors.

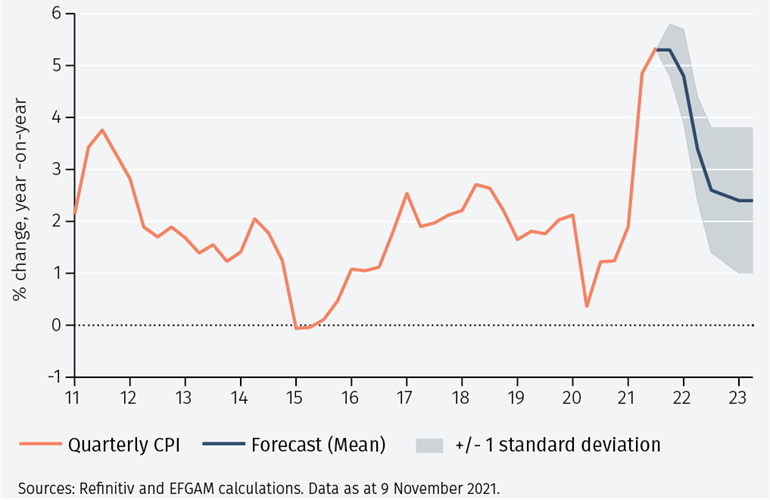

Today, high energy prices reflect strong demand as the global economy is recovering from the pandemic. However, international institutions, including the International Energy Agency and the US Energy Information Administration, expect the oil market to be well supplied in 2022, which should lead to a moderation in prices. This will contribute to a decline in inflation in 2022 (see Figure 5).

Conclusions

Despite concerns raised by many commentators, the risk of stagflation is limited. Economic growth is strong and is expected to exceed potential for several more quarters. Meanwhile, although inflation in many countries has risen to a ten year high and will stay above central banks’ 2% inflation targets for some time, it will moderate in 2022. In this context, the balance of risks for the global economy is tilted towards somewhat higher-for-longer inflation rather than stagflation. After a decade of too low inflation, that should be a welcome development for the global economy and markets.

To continue reading, please use the button below to download the full article.

1 See Infocus, ‘Stagflation:US experiences’, November 2021. https://tinyurl.com/fc89eptn

2 This issue of Infocus refers mainly to the US economy because it leads the global business and financial cycle and because of the availability of long time series of data, but similar trends are characterised in most of the other economic areas.

3 In the emerging markets, also, most central banks pursue an inflation target, often of less than 5%, and are formally independent, although in practice government oversight is often evident. See also de Haan et al., Central Bank Independence Before and After the Crisis, Comparative Economic Studies, 2018.

4 See Farber et al, Unions and Inequality Over the Twentieth Century: New Evidence from Survey Data, NBER Working Paper n. 24587, April 2021.

5 See Devine, Cost-of-living Clauses: Trends and Current Characteristics, Bureau of Labor Statistics, December 1996.

Important Information

The value of investments and the income derived from them can fall as well as rise, and past performance is no indicator of future performance. Investment products may be subject to investment risks involving, but not limited to, possible loss of all or part of the principal invested.

This document does not constitute and shall not be construed as a prospectus, advertisement, public offering or placement of, nor a recommendation to buy, sell, hold or solicit, any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. It is not intended to be a final representation of the terms and conditions of any investment, security, other financial instrument or other product or service. This document is for general information only and is not intended as investment advice or any other specific recommendation as to any particular course of action or inaction. The information in this document does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of the recipient. You should seek your own professional advice suitable to your particular circumstances prior to making any investment or if you are in doubt as to the information in this document.

Although information in this document has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no member of the EFG group represents or warrants its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Any opinions in this document are subject to change without notice. This document may contain personal opinions which do not necessarily reflect the position of any member of the EFG group. To the fullest extent permissible by law, no member of the EFG group shall be responsible for the consequences of any errors or omissions herein, or reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein, and each member of the EFG group expressly disclaims any liability, including (without limitation) liability for incidental or consequential damages, arising from the same or resulting from any action or inaction on the part of the recipient in reliance on this document.

The availability of this document in any jurisdiction or country may be contrary to local law or regulation and persons who come into possession of this document should inform themselves of and observe any restrictions. This document may not be reproduced, disclosed or distributed (in whole or in part) to any other person without prior written permission from an authorised member of the EFG group.

This document has been produced by EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited for use by the EFG group and the worldwide subsidiaries and affiliates within the EFG group. EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority, registered no. 7389746. Registered address: EFG Asset Management (UK) Limited, Leconfield House, Curzon Street, London W1J 5JB, United Kingdom, telephone +44 (0)20 7491 9111.